So much of the pension debate today is filled with "if only" statements. It reminds me of this quote from the Federalist No. 51:

If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

In the famous essay, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton were arguing that we should recognize our failings in how we think about designing government. That acceptance of human nature, however, is rarely embraced in the pension world, where arguments tend to break down over what should happen versus what actually does happen when pension plans are governed by fallible humans. So in honor of Madison and Hamilton, here's my top 10 list of things that would only be true if pension plans were governed by angels:

- If pension plans were governed by angels, they would allow teachers to immediately qualify for retirement benefits, rather than making them wait up to ten years.

- If pension plans were governed by angels, they would provide all teachers with adequate retirement benefits for every year they work, rather than punishing those who stay less than a full career.

- If pension plans were governed by angels, they would encourage veteran workers to retire when it made sense for them, rather than setting one pre-determined age and then nudging them out after that.

- If pension plans were governed by angels, they would offer workers complete portability and reciprocity, rather than imposing stiff penalties on mobility.

- If pension plans were governed by angels, they would provide Social Security to all workers to ensure national portability and progressivity, rather than making them solely dependent on the state-run plan.

- If pension plans were governed by angels, they would make convervative investment assumptions to ensure the plans were fiscally sound and to plan for potential volatility.

- If pension plans were governed by angels, they would invest in low-cost, plain-vanilla investments, rather than chasing after hedge funds and private equity.

- If pension plans were governed by angels, they would invest with their fiduciary responsibility in mind, rather than using their investments to advance political goals.

- If pension plans were governed by angels, they would always make their annual payments, rather than deferring costs to the future.

- If pension plans were governed by angels, they would be fully transparent, rather than hiding the true cost of fees and how benefits work for teachers.

Obviously, none of these things are true, because pension plans are NOT governed by angels. And yet, pension debates proceed as if they are, or as if they could be in the future if somehow our future politicians could act like angels. But that will never be. We should heed Madison and Hamilton's advice, and create ways to avoid these very common human frailties.

Taxonomy:2017 was a busy year for teacher pension reform. Pennsylvania passed a new pension law that moves most government employees, including teachers, into a hybrid pension plan, Michigan followed suit with a reform that automatically enrolls new teachers into a 401k plan over the summer, and Florida began "nudging" teachers into a portable retirement plan. And in Illinois, as part of an upgrade to its school funding formula, the state will help Chicago cover the district’s teacher pension costs.

We’ve been busy here, too. To recap the last year in pension blogging and analysis, I’ve collected some of our most popular and significant work from 2017.

1.Why Do Private School Teachers Have Such High Turnover Rates? Perhaps surprisingly, teachers leave private schools at twice the rate of teachers in public schools. It is unlikely that teacher pensions are a factor in this difference since evidence shows that they do not act as a meaningful retention incentive outside of a small effect for teachers nearing retirement.

2.Retirement Reality Check: Grading State Teacher Pension Plans. Not all state pension plans are created the same. We evaluated the state pension systems in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. Overall, we found that states have expensive, debt-ridden retirement systems in which most teachers fail to qualify for a decent retirement benefit.

3.Illinois’ Teacher Pension Plans Deepen School Funding Inequities. Statewide teacher pension plans exacerbate school funding disparities. This is largely because pensions are based on teachers’ salaries, which are unevenly distributed among schools. After accounting for pensions, the funding gap between high-and low-poverty schools in Illinois doubles. And race-based gaps increase by more than 250 percent.

4.Bayou Blues: How Louisiana’s Retirement Plan Hurts Teachers and Schools. The state’s teacher pension fund is around $12 billion in debt. To stay afloat, schools must contribute more than 30 percent of teacher salaries. Most of which goes to pay down debt. In this report, we describe four ways Louisiana could revamp their system and offer all teachers a path to a secure and more valuable retirement benefit.

And for a bonus, I’ve included the following four blog posts that year-after-year remain among our most popular pieces.

1.What is the Average Teacher Pension in My State? This post is as straightforward as the title. In it, we catalog three key statistics: the average value of a teacher’s pension, the median value, and the percentage of teachers who qualify for a pension.

2.Why Aren’t All Teachers Covered by Social Security? Around 40 percent of teachers do not participate in Social Security. With over half of teachers not qualifying for any pension, this is a real problem that can threaten teachers’ retirement security. Check out our short video to learn more.

3.Colorado’s Unreal Teacher Retirement Plan. In Colorado, teachers and the state make extremely large contributions to the pension system. In fact, every teacher who started teaching at 25 remains in the classroom would be a millionaire by age 54. So why isn’t Colorado filled with millionaire teachers? Debt. The state has $14 billion in pension debt that eats up a lot of the pension contributions made on behalf of teachers.

4.A Tale of Two Teachers: A Retirement Story. For teacher pensions, where you teach matters. When you start teaching also matters. If you move across state lines, you also can adversely affect your pension value. In short, two teachers who retire at the same age and teacher for the same length of time can end up with very different levels of pension wealth. Check out our short video to learn more.

Nationally, teacher pension funds have amassed more than a trillion dollars in assets. But those funds cannot just sit in a bank somewhere; that money needs to grow. It needs to earn high returns so that pension funds can pay down debts and meet burgeoning financial obligations to their members. In fact, states often base how much they need to save today on ambitious assumptions about the expected rate of return they’ll get on their investments.

Most pension funds engage in a strategy that’s called active investing. Under this approach, money managers make decisions about which company’s stock should be bought and sold, and when. With smart people making such decisions, the idea is that active investing will produce greater financial gains than a “passive” approach of regularly buying an index of equal amounts of all companies in the market.

The evidence, however, tells a different story.

As Ben Carlson, the author of A Wealth of Common Sense, pointed out in a tweet earlier this fall, over the last 15 years “passive” index funds overwhelmingly outperformed traditional, “actively” managed mutual funds. Among the different types of funds analyzed, index funds outperformed the actively managed mutual funds at least 80 percent of the time. In many cases, index funds performed even more strongly. For example, small-cap growth funds were outperformed by their benchmark 99.35 percent of the time.

These data suggest that passive investing could provide a safer and, over the long-term, a more productive investment, for teacher pension funds. Passive investing, such as through an index fund, spreads investments widely. This produces a highly diversified portfolio that covers the entire market, rather than trying to make guesses about which particular companies or sectors will do well at a given time. This strategy insulates investors from more dramatic swings of volatility in individual stocks and, as shown above, can often produce returns that outperform managed accounts.

Taking a more passive investing approach could benefit teacher pension funds in other ways as well. Passive investing also typically incurs lower fees, meaning teacher pension funds can pay less for these returns on their investments. Furthermore, electing to passively invest will severely reduce the need for pension fund employees to pick the right money managers, who in turn will pick the right investments. Studies of this practice suggest that it’s a lose-lose situation, that investors tend to chase after positive performance rather than capturing it themselves, and that states might be better off making passive investments with a leaner team.

As an added bonus, passive investing would help to eliminate some of the politics around pension funds. As my colleague Chad Aldeman previously noted, the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) black-listed certain money managers who ran afoul of the union’s priorities. Or conversely, some unions will attempt to make socially conscious investments such as avoiding weapons manufacturers. Passive investing allows pension funds to avoid these political issues.

To be sure, passive funds are not fool-proof. They follow the market, and if the market tanks so will they. A passive investment also won’t produce dramatic returns like someone who bought Amazon stock in the mid-1990s, or Bitcoin in more recent years. But index funds produce a greater than average return when the market is doing well, and can limit losses during a downturn. It is precisely this kind of investing strategy that pension funds need to grow their assets and meet their members’ financial needs.

Taxonomy:I was recently chatting with an education-sector friend who asked about good side jobs for teachers, and it gave me pause. I wasn’t put off by the question, per se. I had spent my own teaching years making extra cash with regular babysitting gigs, summer school classes, and a paid testing coordinator position. But when I actually stopped to think about it, the best second job for a teacher is no second job.

Teachers, no matter how new, shouldn’t need a side hustle to make ends meet.

But, conservatively (and without including summer work), 16 percent do.

Put simply, we don’t pay teachers enough. This is true by multiple measures. In 2015, American teachers’ earnings were 17 percent lower than comparable college-educated workers in other developed nations. There are countless factors tied up in this, gender included. The Teacher Salary Project has more, but that’s a whole other blog post. Or six. How do we make it better?

One solution? Pension reform. Right now, states pay, on average, $6,800 per teacher toward pension debt. These payments aren’t going to future benefits, but instead to pay down existing debts. If we compare those numbers to the amount teachers report earning through side hustles, teachers in at least 47 states and Washington D.C. would benefit (these states have at least some pension debt that’s costing teachers money) and of those, 26 (highlighted below) would out-earn their average side hustle. Without pension debts, states could raise salaries enough that teachers wouldn’t need to spend their free hours waitressing or driving for Uber.

* Maine and Ohio do not report debt separately

Pensions are often touted as a retention strategy. But in fact, studies show defined benefit plans do very little to entice new and mid-career teachers to stay, and only marginally push or pull veteran teachers’ decisions. It may be that a fair salary, one providing family sustainable wages, would be an even stronger retention strategy. To be sure, finances are not the first reason teachers cite for exiting, but in the most recent national survey, 18 percent of teachers who left the profession attributed their decision to financial reasons.

Teachers deserve to feel valued while they are on the job, not just in retirement. And if teachers are forced to take on second jobs to make ends meet, many may be pushed out of the profession before they qualify for a decent retirement benefit. Pension debts affect all teachers, but they’re paying for retirement systems that only benefit a fraction of them.

Last month, I wrote about a recent report comparing apples and oranges. More precisely, the National Public Pension Coalition (NPPC) claimed that state-run defined benefit plans offered better benefits than defined contribution plans.

As I pointed out at the time, the NPPC report ignored how much money was going into each of the plans, and they looked only at the retirement benefits offered to 35-year veterans, which sidestepped the question of how benefits accumulate over time.

But what if we take their comparison seriously and show what retirement benefits actually look like over the full career of a teacher? Before I show you the results, consider the inputs.

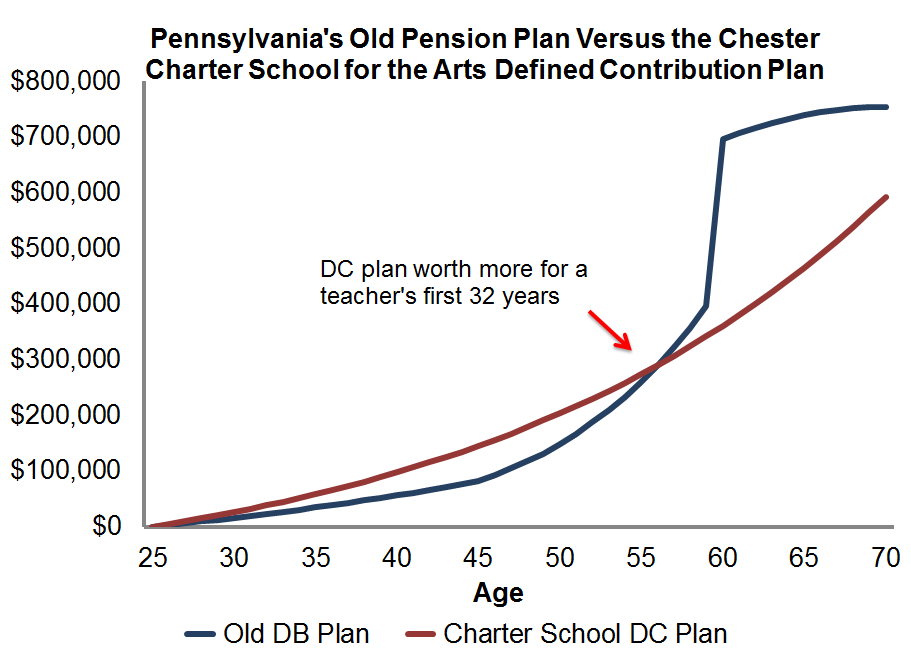

The NPPC report compared charter schools to traditional pension plans in eight states, California, Florida, Indiana, Louisiana, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Since I already had data on the traditional defined benefit pension system in Pennsylvania, I decided to focus there. Although Pennsylvania recently made changes to its retirement plan for new teachers, for illustrative purposes I’m going to show the system for current teachers. From the NPPC report, I pulled info on the defined contribution plan offered in their Pennsylvania comparison school, the Chester Charter School for the Arts. I assumed immediate vesting in the 403(b) plan, but otherwise I took the same investment return and inflation rate assumptions as the NPPC used*. Here’s what those plans look like:

Pennsylvania’s Traditional Defined Benefit Plan

Chester Charter School for the Arts 403(b) Plan

Employee contributions (as a % of salary)

7.5%

6%

Employer contributions for benefits (% of salary)

8.31%

6%

Employer unfunded liability (% of salary)

20.89%

N/A

Total contributions (% of salary)

36.71%

12%

Investment return assumption

7.25%

6%

Inflation assumption

2.75%

2 %

Vesting period

10 years

Immediate

Formula multiplier

2%

N/A

Normal retirement age

Age 65 w/ 3 years of experience, or any age w/ 35 years of experience (and age + experience is greater than 92)

N/A

As the table shows, it’s obvious that the NPPC report is comparing apples and oranges. To begin with, the contributions into the system are different. Teachers and employers are contributing far more money into Pennsylvania’s state-run defined benefit plan than they are into the Chester Charter School 403(b) plan. However, the state plan has run up huge unfunded liabilities, so traditional Pennsylvania districts are also contributing almost 21 percent of each teacher’s salary just to pay those down. After accounting for those liabilities, the traditional Pennsylvania system costs three times as much as what the charter school is offering.

As it will be clear later, when it comes to pension plans, retirement plan costs do not always translate into retirement plan benefits, and the Chester Charter School is offering a pretty good retirement plan. Its 6 percent employer match would put it in the top 10 percent of private retirement plans nationwide, and the total employer plus employee contribution rate of 12 percent should provide at least a floor of adequate retirement benefits. (Unlike teachers in 15 other states, Pennsylvania teachers in both plans are enrolled in Social Security.)

Ok, on to the results. In the graph below, the blue line shows how benefits accumulate under Pennsylvania’s old defined benefit plan. As in other states, benefits accrue very slowly for many years, and it isn’t until teachers near the state’s 35-year mark that the pension value really starts to climb. In contrast, the red line shows how retirement assets would accumulate under the Chester Charter School for Arts plan. Workers at all ages are accruing decent retirement benefits, regardless of how long they stay.

So which plan is “better” for teachers? The NPPC is right to point out that a 35-year veteran is better off under the old Pennsylvania defined benefit plan, at least based on retirement benefits alone. But that’s only part of the story. Remember that more than a third of her salary is going to pay for that benefit, and only a select group of teachers will reach that peak. According to the state’s own estimates, less than 1 percent of Pennsylvania teachers will stay that long. After zooming out and looking across the full working career, it becomes clearer that a portable benefit plan would be better for most teachers.

*For the sake of argument, I’ve taken the NPPC’s investment and inflation assumptions verbatim, but those result in a far lower return than what Pennsylvania assumes in its official projections. It’s not the main point of this post, but recent research has questioned whether defined benefit plans really earn a premium above what individuals earn in their defined contribution plans.

This piece was coauthored by Chad Aldeman and Max Marchitello

State teacher pension systems are in serious need of reform. Aside from skyrocketing costs that eat up a growing portion of states’ education budgets, teacher pensions simply do not provide the majority of teachers with a valuable retirement benefit. Whether because they don’t meet the vesting requirements, they move states, or only teach for a portion of their career, more than half of teachers either do not earn any pension, and less than one-in-five earn a full pension.

Despite these problems, states are still slow to change. One possible reason for that reticence is a misconception that under-funded plans need an influx of new teachers to help pay down past debts. That is, there’s a belief that closing existing plans would destabilize the system for all current teachers and retirees.

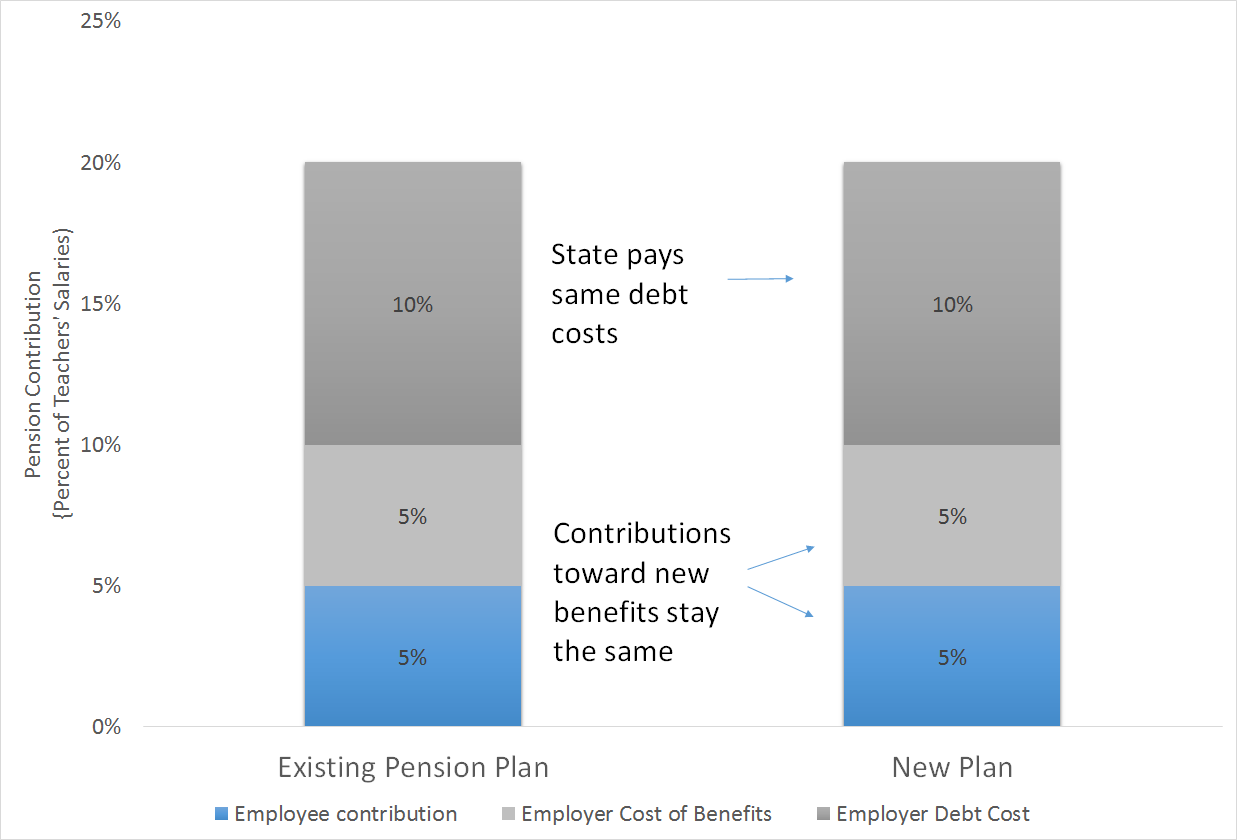

Fortunately, this need not be the case. In fact, switching new teachers to a new type of retirement plan, such as a defined-contribution plan, can be cost neutral.

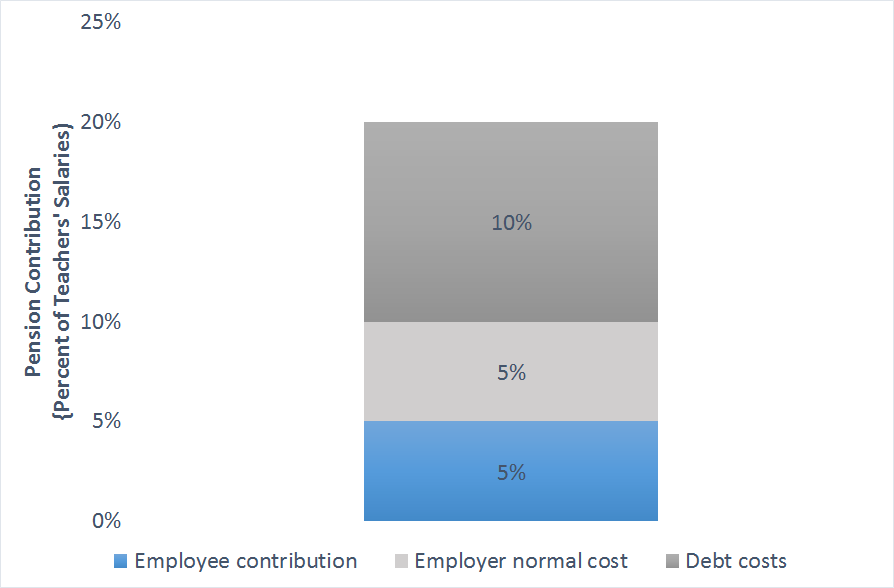

Consider the following example of a state with a total pension contribution of 20 percent of teachers’ salaries. In this example, teachers contribute 5 percent of their salary and employers contribute 15 percent of each teacher’s salary. Unfortunately, two-thirds of that employer contribution, or 10 percent of each teacher’s salary, has to go toward paying down past debt, and only 5 percent goes toward paying for actual teacher benefits (what actuaries call the “normal cost” of the plan). We chose round numbers here for illustrative purposes, but they are broadly representative of the average teacher pension plan today.

Now let’s look at how a state can close the plan to new employees and still keep paying down its debt. In the example below, all teachers keep making the same 5 percent contribution. The 10 percent of teacher salaries necessary to pay down debts remains constant. However, since new teachers will be enrolled in a defined contribution plan, they will not have a “normal cost,” but instead a direct 5 percent contribution toward their retirement fund. The total costs to the system stay the same, and teachers receive the same value of retirement savings, but new teachers are now enrolled in a new plan with more portable benefits for them and no more debt accruals for the state.

Now, we're simplifying a bit here. Pension plans would have to adjust their investment strategies as more of their membership aged closer to retirement, just as individuals must do with their own investments. Plans with young members can take more risks, because they won't have to pay benefits for many years in the future. Once a state closes a plan, the membership will slowly age over time and plans would need to make more conservative investments. Still, that transition could take place over decades, as current workers gradually age into retirement, and states could instead phase in changes slowly over time. On a cumulative basis played out over decades, the costs of these changes would be relatively small, and meanwhile the state would stop adding to their current debt loads.

To be clear, some recent pension reform proposals have come with high price tags. But those are not because of the change in pension plans. Rather, in the case of recent proposals in Kentucky and Michigan, the increased costs were due to the fact that the states were simultaneously shifting new workers into a new system AND changing the way they paid down existing debts. Sort of like a homeowner switching from a 30- to a 15-year mortgage, those states are attempting to front-load their costs to pay down their debts more responsibly. While this is also a good idea, it's separate from the change in retirement plans.

All of this is to say that states can make the shift to new retirement plans easier than pension advocates claim. They could enroll new teachers in a new retirement system without incurring much in the way of additional costs, stop adding to their already large pension debts, and better serve the majority of teachers.