More money for schools is good news. It’s even better when a large portion of those funds will be distributed equitably across the state. In California, the state recently approved a new budget that includes a one-time payment of roughly $1 billion for the state’s school districts. This amounts to more funding than is required by the state funding formula. It’s big news.

But don’t pop the champagne just yet.

School district expenditures for the state’s teacher pension fund (CalSTRS) will increase by more than $1 billion annually until 2020-21. In other words California will need to make this onetime payment every year until 2021 to fill the budget gap created by the increase in districts’ pension spending. As it stands now, the state’s school districts will be around $3 billion short.

Without any additional help, districts will likely need to cutback in other education expenditures to be able to fund the pension system. This consequence makes clear that pension spending cannot be separated from school funding. One affects the other.

Unfortunately, the new state budget won’t help either despite allocation an additional $6 billion from the state’s reserves to pay its public employee pension fund. Nearly doubling the state’s investment into the public pension system this year will reduce the fund’s long-term debt and save taxpayers billions in the long run. And while that is good news for the state’s own pension obligations, it will do nothing to help districts make their payments this year.

California may at first look like it is increasing funding for school districts, but in reality this budget serves only to blunt the impact of rising pension costs for a year. It’s a Band-Aid too small to cover a gaping wound. Barring a massive increase in K-12 education spending, pension reform is necessary to actually grow school district budgets and to direct more funds to schools.

Last winter, I wrote about an effort in Michigan to reform the state's teacher retirement plan. At the time, Republican lawmakers were pushing to close the state's defined benefit pension plan to new workers and instead enroll all new teachers in a defined contribution plan identical to the one offered to other state employees.

In anticipation of a similar bill coming up again this year, we created a Michigan-specific version of our 3-minute pension "explainer" video. If you want a simple, easy way to quickly understand the debate over pensions in Michigan, you might start with the video below:

As fate would have it, the story we articulate in the video is now playing out in Michigan. Legislators continued to push for reform, and this week they agreed on a new version of the bill. It would set a portable defined contribution plan as the default, but it would also allow teachers to opt-in to a pension plan if they chose to. The authors of the bill argue it would be better for teachers and taxpayers, but Michigan union groups are attacking the bill as being anti-teacher.

Who's right? Well, consider how bad Michigan's plan is today. In a report released this week, we analyzed every state's teacher retirement plan. Along with most other states, Michigan earned an "F" grade. Here are the basic stats:

- Only about half of all incoming teachers will stick around for 10 years, the minimum required to earn a pension;

- Less than one-in-ten young teachers will teach in Michigan for their full career and reap the large back-end benefits promised to them;

- The current "hybrid" plan is dominated by its defined benefit component, and it has no way to keep costs in check over time if its assumptions prove inaccurate; and

- Michigan districts are currently contributing about 22 percent of each teacher's salary toward the pension plan, but most of that is being used to pay down past debts, not to pay for actual teacher benefits. In fact, about 80 percent of school district contributions toward the pension plan today are going to pay off past debts, not as benefits for current workers.

Combined, this leaves Michigan teachers in an expensive, back-loaded system. The vast majority are losing out in terms of retirement benefits, and all of them are losing out because their employers have to keep paying down pension debts.

The new legislation won't solve the state's existing debt problems, but it will prevent the state from accruing new debts in the future. And more importantly, it will enroll new teachers in a portable defined contribution plan, with a shorter vesting period and more money going toward teacher retirements. That will cost the state more money, but it's a win for teachers.

Taxonomy:Whoever wins New Jersey’s Governor race in November will face a growing financial crisis. The state’s government employee pension fund is in dire financial straits. In fact, the fund is in the worst financial shape of any in the country. Now, the state has just over $49 billion in debt, and New Jersey’s local governments have another $17 billion in unfunded liabilities. The state’s teacher pensions owns the largest share of the problem. It is funded at less than 50 percent and is by itself $30 billion short. In fact, New Jersey’s teacher pension plan scored an F according to our new ranking of all 50 state teacher pension plans.

So what do the gubernatorial candidates propose to do?

Republican Kim Guadagno, the state’s current Lieutenant Governor, would tackle the pension crisis in four ways. First, she wants to increase the number of public employees enrolled in a cash-balance plan rather than the state’s pension fund. These plans are much like 401k retirement accounts, but they carry a guaranteed (but usually more conservative) interest rate. She then wants to find savings by cutting back on “Cadillac” health benefits. Third, she would like to ensure that government employees don’t simultaneously receive a paycheck and a pension, and, finally, she would cut fees paid to Wall Street firms investing those pension dollars. Guadagno believes this multifaceted approach will solve New Jersey’s pension woes.

The other candidate is Phil Murphy, a Democrat who served as President Obama’s top diplomat to Germany and a former Goldman Sachs executive. Murphy has some experience working to reform pensions. In 2005, he served on a task force to reform pensions. His plan is to divest from private equity and hedge funds, reinvest the millions paid in fees to those funds, and to close tax loopholes. Murphy argues that together these actions will fix the problem and allow the state to meet its pension obligations to government employees.

There are things to like about both the Republican and Democrat proposals.

Guadagno’s plan to increase the share of public employees in a cash-balance plan would help in a few ways. For teachers, for example, a cash balance plan typically provides a more valuable retirement benefit for a majority of educators. Furthermore, shifting more public employees into a DC plan will slow down the growth of New Jersey’s pension debts.

Decreasing the rapid accrual of pension debt is critically important, but it won’t be sufficient to ensure that the state can meet its current obligations. On that front, Murphy put forth a strong proposal. His goal of closing tax loopholes would secure significantly more revenue for the state to direct to its pension obligations and ensure that retirees receive the full benefits they earned.

The truth of the matter, however, is that whether Guadagno or Murphy wins in November, their individual proposals alone are likely not enough to solve New Jersey’s pension problems. The best strategy for the victor would be to borrow the elements of their opponent’s proposal described above. Together, this would be a stronger approach that would increase funding for existing pension obligations, slow down debt accrual, and provide higher quality benefits to many public employees.

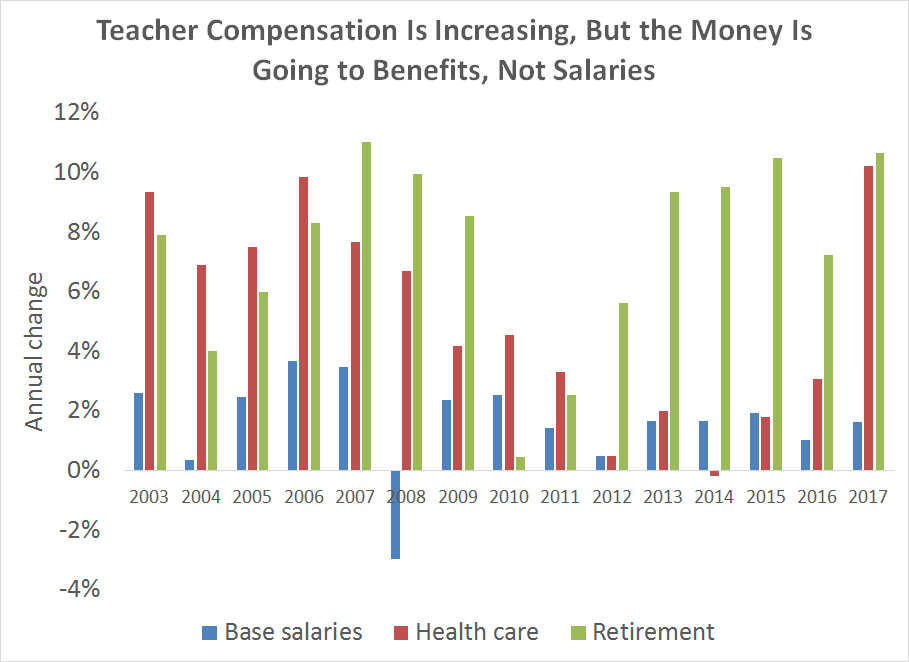

A year ago, we released The Pension Pac-Man: How Pension Debt Eats Away at Teacher Salaries, which showed that, over the last 20+ years, teacher salaries have not kept up with inflation, but total teacher compensation has. That's due in large part to rising pension costs that, like the proverbial Pac-Man, are eating further and further into teacher compensation.

As the Wall Street Journal reported over the weekend, this trend is broadly true for all American workers. But the magnitude is much larger for public school teachers. As we showed last year, teachers have higher retirement costs than any other major group of workers, even other public-sector employees. As a percentage of their total compensation package, teacher retirement benefits eat up twice as much as other workers.

This trend has not abated. The graph below uses data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to show the annual change in employer costs by category. Over the last 15 years, teacher salaries have risen an average of 1.6 percent per year. That's less than inflation. In comparison, insurance costs are teachers have risen by 5.2 percent per year. That's a lot, but retirement costs have risen even faster, by 7.4 percent per year.

Most of these costs are due to rising pension debts, not to pay for actual teacher retirement benefits (see Figure 3 here). Until states get their debt costs under control, teachers will continue to see higher and higher shares of their compensation eaten up by retirement costs, with less and less money going into their pockets.

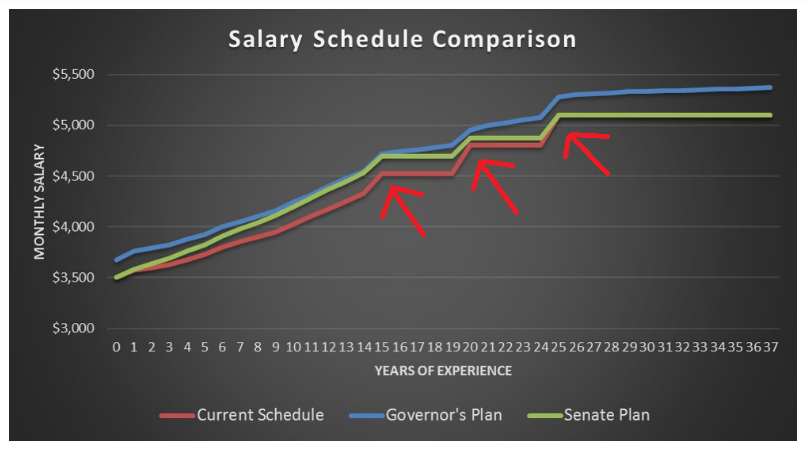

Taxonomy:I recently read a story about the statewide teacher salary schedule in North Carolina. Politicians there are debating various changes for the upcoming year, but what caught my eye was the weird way North Carolina pays its teachers.

I pulled the graphic below, from a blog by The Progressive Pulse, to show what I mean. The graph shows the current salary schedule (in red) versus two competing proposals from the Governor and state Senate. My focus was on the red line. North Carolina teachers earn very small raises (of 0.5 to 2.5 percent) from years 1-14, and then they earn a 4.6 percent raise upon reaching 15 years of experience, then nothing until year 20, when they get a 6 percent bump, and then nothing again until year 25, when they get another a 6.25 percent bump. I added the arrows pointing to these weird kinks.

It's easy to imagine how North Carolina got to this place, but those back-end lumps are not tackling North Carolina's real turnover problems. Like every other state, the bulk of North Carolina's teacher turnover happens in the early years, and the vast majority of its incoming teachers will never reach these back-end bonuses (the state estimates only 28 percent will reach the 15-year mark). Worse, these back-end salary bumps are also not doing much to shape the retention decisions for those teachers who do reach them, at least not according to the state's pension plan.

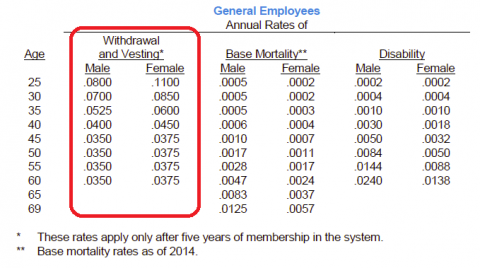

To show what I mean, I pulled the graphic below from the Actuarial Valuation report from the Teachers’ and State Employees’ Retirement System of North Carolina. I drew a red circle over North Carolina's official estimates for how many teachers will leave each year, based on their age. North Carolina has a separate set of assumptions for teachers in their first four years on the job, but it switches to these age-based estimates after that. (The chart can be read as, "For 25-year-old females, North Carolina assumes 11 percent will leave the state's public schools in that given year.)

Note that, while North Carolina's statewide salary schedule is based on years of experience, the state pension plan hinges the bulk of its assumptions on age, not years of experience. That is, after four years, the pension plan does not feel the need to account for the salary schedule's age-based longevity incentives. Even if there were a connection to years of experience, the state is not assuming any bumps in retention rates tied to any particular age.

To put it bluntly, North Carolina's pension plan does not assume that its statewide teacher salary schedule is affecting turnover rates.

This isn't unusual. The New York City teacher salary schedule has weird kinks at years 10, 13, 15, 18, 20, and 22. For example, after receiving no raise in year 21, a New York City teacher earns a $5,511 raise in year 22, a bump of 5.8 percent. But New York City's own pension plan doesn't assume this matters enough to affect its financial situation. Here are the corresponding withdrawal assumptions for the Teachers’ Retirement System of the City of New York:

This is a pretty straightforward chart. (It can be read, "New York City assumes 9 percent of teachers with 0-5 years of service will leave within the next year.") New York City is assuming that teacher turnover rates fall every five years. This is a much less incremental approach than the assumptions North Carolina uses, which makes it even more obvious that New York City's salary bumps at years 10, 13, 15, 18, 20, and 22 are not doing enough to shape teacher behavior to warrant adjusting the pension plan's assumptions.

Now, it's possible that teachers are responding to these lumpy incentives, and the pension assumptions simply aren't fine-grained enough to detect them. But that means something too. Those pension plan assumptions are the basis for consequential financial decisions about how much the state or city needs to save today in order to pay benefits in the future. While states and cities are spending a lot of money on back-end incentives like this, their own pension plans don't think it's worth altering their assumptions to account for them.

My colleague Kelly Robson and I have a new paper out in Education Next this week looking at the interaction between pension plans and teacher retention. We had two main findings. One, pension plans themselves do not assume that teachers change their behavior in order to qualify for a pension. And two, while there may be some late-career retention effect as teachers at the end of their career hold on in order to maximize their pension, state pension plans assume a much larger "push-out" effects that causes large numbers of veteran teachers to retire at relatively young ages.

I'll come back to the second point in a subsequent post, but I'll start with the lack of early-career retention effects. If qualifying for a pension were an incentive, we should see teachers change their behavior in order to "vest" and reach their state's minimum threshold. That is, teacher turnover rates should flatten out in the years leading up to the vesting period, and then spike upwards, at least somewhat, immediately afterwards. For example, if teachers in a given state qualified for a pension after five years, teachers in their fourth year should be marginally less likely to leave their jobs as they near that point. After all, these teachers would qualify for a guaranteed stream of pension income every month upon retirement if they stay just one more year. Then, some teachers who held on to year five solely to qualify for a pension would leave the profession and retention rates would rise.

We tested this empirically using the pension plans' own financial assumptions. Each state pension plan publishes “withdrawal” rate tables estimating the percentage of teachers who will leave (aka withdraw from) the pension system in a given year. State pension plans publish these withdrawal rate assumptions in their Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports (CAFRs). Though these rates reflect each state’s predictions for the future, states update them regularly based on their own historical patterns.

States present their withdrawal assumptions in tables similar to the figure below, which is an example from Alabama. The table can be interpreted as follows: For 25-year-old female teachers with 0 years of service, Alabama assumes that 14 percent will leave by the end of their first year. The state assumes another 14 percent will withdraw when this cohort of teachers is 26, 27, 28, and 29 years old. When they reach age 30 with five years of teaching experience, the state assumes the annual withdrawal rate for this group drops to 5.8 percent.

This table can be used to determine whether Alabama believes its 10-year vesting requirement to qualify for a pension is shaping teacher behavior. If it were, we should see slightly lower turnover rates in years eight and nine, as teachers hold out for a pension, followed by a small spike in year 10 as teachers who were remaining solely to qualify for a pension finally departed. But that’s not what Alabama assumes. Across all ages and experience levels, Alabama expects withdrawal rates (for non-retirement purposes) to decline the longer a teacher remains in the profession. It does not assume there will be holdouts prior to the pension threshold who leave upon qualifying for it. Again, Alabama is making these assumptions based on its own historical data.

In fact, after looking at every state's assumptions, we could find no evidence of any state pension plan that believes its teachers will systematically change their behavior to qualify for a pension. Instead, teachers become less and less likely to leave the profession (for non-retirement reasons) every year they remain, and there is no indication that qualifying for a pension affects that trend one way or another. Given the large numbers of teachers who leave early in their career, about 60 percent of Alamaba teachers and about half of all new teachers nationwide don't stick around long enough to qualify for a pension. Although they and their employer are contributing large sums of money to the pension plan, they won't earn a pension at all, and the pension plan won't be enough to keep them in the profession. That's bad for those teachers in terms of retirement savings, and it's bad for employers who could have used that money in more productive ways.

In a subsequent post I'll turn back to later-career teachers. In brief, pension plans do appear to exert a limited “pull” effect that keeps some late-career teachers on the job (remember, most teachers have left before then). But pension plans exert an even stronger “push” effect that encourages veteran teachers to retire, regardless of any teacher’s particular interest or ability to continue teaching. Because veteran teachers tend to perform better than a replacement teacher just entering the profession, that has real, negative consequences for students.