Earlier this month I was invited to speak about teacher pensions at a meeting of the Taxpayers Association of Central Iowa. Although the costs of Iowa’s pension system (IPERS) are rising, my presentation focused on the benefits side of the equation: Is Iowa’s pension plan good for the state’s teachers? Are there other alternatives that could provide better benefits?

My full slide deck attempting to answer those question is at the bottom of this post. I centered my presentation on three basic myths about pensions:

- The myth that traditional pension plans take all the risk on behalf of teachers;

- The myth that traditional pension plans help retain teachers; and

- The myth that traditional pension plans offer better benefits than alternative models.

Like any good myth, each of these has some kernels of truths behind them, but they obscure a larger story.

First, it’s true that pension plans do take a number of risks on behalf of workers. In Iowa, as in most other states, teachers don’t have to decide whether to save for retirement, how much to contribute, or how to invest their savings. The state takes care of those decisions for them. The state also takes care of decisions about how to draw down retirement assets. Rather than having access to one lump sum, the state pension plan issues qualifying retirees monthly checks throughout their retirement years.

But those advantages still leave some risks on the table for Iowa teachers. Pension formulas are complicated, and teachers often make bad decisions about whether they should take a pension or withdraw their contributions. Traditional pension plans can also take on debt when their promises exceed their savings, and those costs trickle down to teachers in real ways.

Worse, pension plans tend to be heavily back-loaded, meaning they only deliver decent retirement benefits to teachers who stay for 20 or 30 years. For a variety of personal and professional reasons, most teachers don’t stay that long. When a teacher starts her career, she faces the risk that she will need to move states and start over, or that she may just not like teaching as much as she thought she would. Pension plans leave most teachers exposed to this “attrition risk," the risk that they’ll leave before qualifying for decent retirement benefits.

Second, there’s a myth that pensions help retain teachers in the profession. If that were true, we should see teachers changing their behavior in order to qualify for a pension in the first place. But we don’t. Iowa, for example, requires teachers to stay for 7 years in order to qualify for a pension. If Iowa teachers truly valued their pensions, we should see some fraction of 6-year veterans alter their behavior to reach the 7-year mark. But that doesn’t show up at all, even in the state’s official actuarial assumptions. Pensions do seem to help retain later-career teachers, although the existing evidence suggests that effect is limited to teachers who are very close to reaching their retirement age.

In contrast, pension plans clearly have a push-out effect on later-career teachers. In Iowa, teachers start leaving in large numbers starting at the state’s early retirement age of 55 and accelerating at age 57. Even among Iowa teachers who make it to age 55, the state assumes only about 3 percent will make it all the way to age 65 (the normal retirement age for Social Security). When researchers have tried to weigh the balance between retention and push-out incentives in traditional pension plans, they’ve found that the push-out effect is much stronger. The truth is that states are using their pension plans to push out veteran teachers from the classroom, which has a negative effect on student learning.

The third myth is that the existing system is the best way to deliver benefits for teachers. In fact, there are multiple ways states could structure benefits that would leave all teachers better off.

In Iowa, I looked at three different alternatives—a cost-neutral cash balance plan, a cost-neutral defined contribution plan, and a defined contribution plan offered to Iowa state university employees. The cash balance would guarantee all teachers a pre-determined rate of return—5 percent in this example—and provide a steady accrual of retirement benefits rather than the current back-loaded system. I also modeled two different defined contribution plans, one using Iowa’s current teacher pension contribution rates, and the other using the same contribution rates as Iowa offers to its state university employees. Ironically, Iowa is paying about the same amount for each of these last two plans (contributing a total of 15 percent of salary), but the difference is that the teacher plan has debts, while the state university plan does not.

Most teachers would be better off in one of these alternative plans. Depending on the plan, between 73 to 78 percent of teachers would have more retirement savings under the alternative model. In addition, because none of these alternatives would accumulate further debts, all teachers would see higher take-home pay.

My main lesson for Iowa policymakers is that retirement plans should be for workers, not the state. Iowa’s main goal should be providing a path to a secure retirement to all of its teachers, no matter how long they choose to stay. Iowa’s current pension system isn’t accomplishing that goal, but there are readily available alternative plans that could.

To learn more about Iowa’s teacher pension system, click through my slides below:

State-based teacher pension plans are important. They make up an enormous portion of local K-12 budgets, and the vast majority of them are underfunded. But despite their weight, or maybe as a symptom of, the intricacies of these systems can be difficult to navigate. The National Council on Teacher Quality’s recent report, Lifting the Pension Fog, works to demystify the topic. The NCTQ team, in partnership with EdCounsel, collected teacher retirement data from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. We’re eager to build on their work in a forthcoming piece; they’ve provided a lot to work with. One data point that stands out though, is rising contribution rates.

NCTQ researchers found that just eight states have reasonable contribution rates – which they define as a combined contribution rate of 10-15 percent of salary. Unfortunately, a significant portion of pension contributions today are going toward debt costs – not to teachers themselves (see Figure 3 here). We’ve written about this before, but the short of it is that today’s new teachers are paying for years of pension system underfunding in the form of lower benefits and stagnant salaries. State pension debts are posing risks to hiring and retaining a quality teaching workforce.

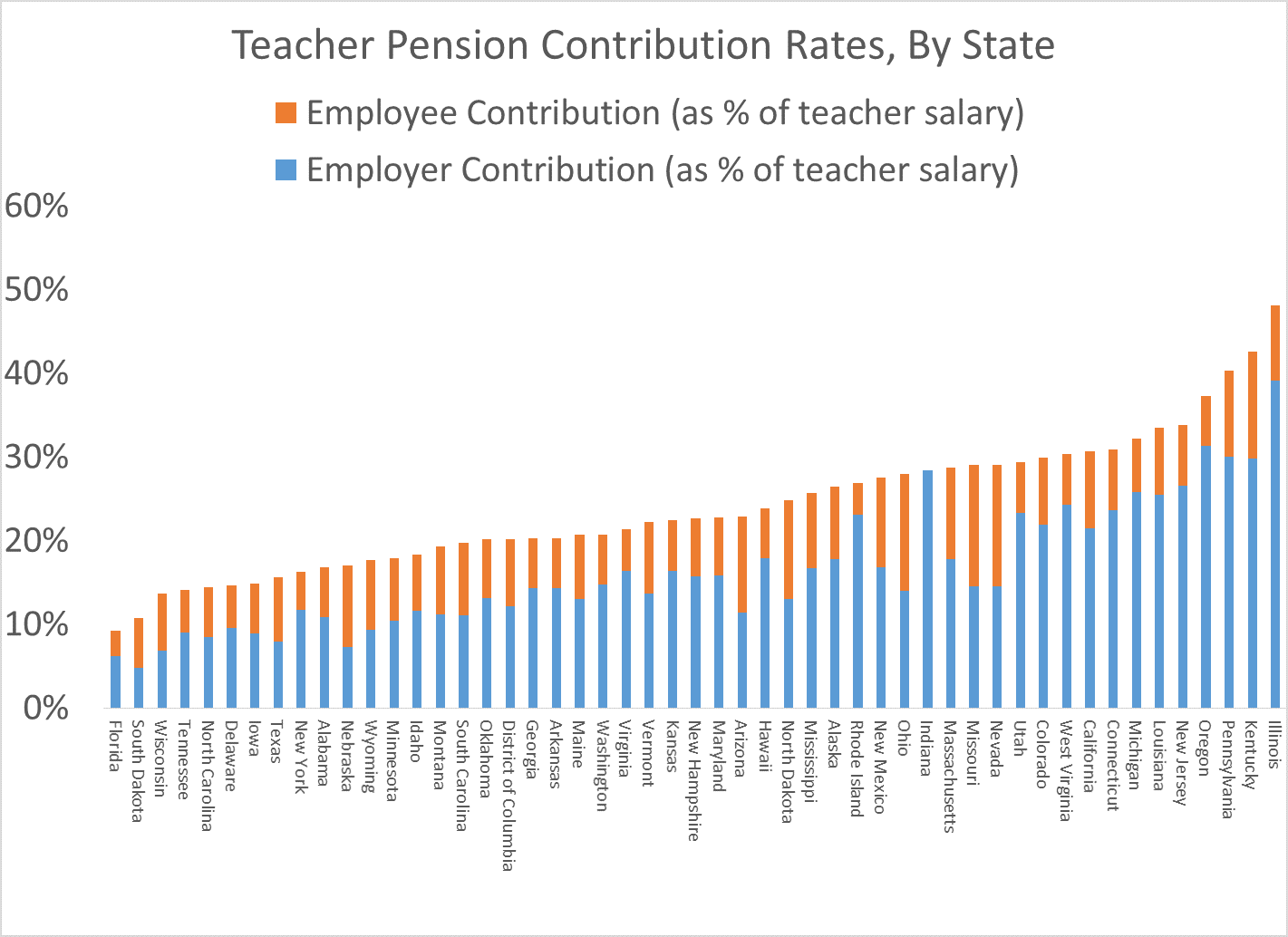

But employer contributions are just one part of the plan. The graph below shows total teacher pension contribution rates (the table at the bottom of the post has the same data in text format). The blue bars represent the employer contribution (which can come from the state, a district, or both), and the orange bars represent the employee’s share.

As the graph shows, the total contribution rates are daunting. The average is now 24 percent, and states like Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Illinois are all contributing over 40 percent of a teacher’s salary into their state retirement system. Other states are heading in that direction.

Both teacher and employer contributions have been trending upward. Since 2008, 30 states have increased teacher contributions. In 1982, only 13 state plans had employee contribution rates of 7 percent or above. Today, 29 do.

When teachers are asked to pay higher contributions for the same benefits, that makes it even less likely that they’ll earn pensions worth more than their own contributions plus interest. That hurts new and future teachers the most. Rising contribution rates do not significantly impact teachers who were already members of the retirement system – often, they’ve already worked most of their careers under the plan’s earlier, lower employee contribution rates. It’s the newest hires who take the brunt of a higher employee contribution, all while paying off the debt costs of a plan they are statistically unlikely to benefit from.

State

Employer Contribution* (as % of salary)

Employee Contribution (as % of salary)

Total Contribution (as % of salary)

Alabama

10.82%

6.00%

16.82%

Alaska

17.78%

8.65%

26.43%

Arizona

11.34%

11.50%

22.84%

Arkansas

14.30%

6.00%

20.30%

California

21.41%

9.21%

30.62%

Colorado

21.94%

8.00%

29.94%

Connecticut

23.65%

7.25%

30.90%

Delaware

9.58%

5.00%

14.58%

District of Columbia

12.17%

8.00%

20.17%

Florida

6.21%

3.00%

9.21%

Georgia

14.27%

6.00%

20.27%

Hawaii

17.89%

6.00%

23.89%

Idaho

11.57%

6.79%

18.36%

Illinois

39.12%

9.00%

48.12%

Indiana

28.41%

0.00%

28.41%

Iowa

8.93%

5.95%

14.88%

Kansas

16.38%

6.00%

22.38%

Kentucky

29.755%

12.86%

42.61%

Louisiana

25.51%

8.00%

33.51%

Maine

13.01%

7.65%

20.66%

Maryland

15.79%

7.00%

22.79%

Massachusetts

17.73%

11.00%

28.73%

Michigan

25.78%

6.40%

32.18%

Minnesota

10.37%

7.50%

17.87%

Mississippi

16.65%

9.00%

25.65%

Missouri

14.50%

14.50%

29.00%

Montana

11.16%

8.15%

19.31%

Nebraska

7.25%

9.78%

17.03%

Nevada

14.50%

14.50%

29.00%

New Hampshire

15.67%

7.00%

22.67%

New Jersey

26.55%

7.20%

33.75%

New Mexico

16.78%

10.70%

27.48%

New York

11.72%

4.50%

16.22%

North Carolina

8.47%

6.00%

14.47%

North Dakota

13.04%

11.75%

24.79%

Ohio

14.00%

14.00%

28.00%

Oklahoma

13.11%

7.00%

20.11%

Oregon

31.26%

6.00%

37.26%

Pennsylvania

30.03%

10.30%

40.33%

Rhode Island

23.13%

3.75%

26.88%

South Carolina

11.09%

8.66%

19.75%

South Dakota

4.74%

6.00%

10.74%

Tennessee

9.04%

5.00%

14.04%

Texas

7.92%

7.70%

15.62%

Utah

23.31%

6.00%

29.31%

Vermont

13.63%

8.53%

22.16%

Virginia

16.32%

5.00%

21.32%

Washington

14.78%

5.95%

20.73%

West Virginia

24.32%

6.00%

30.32%

Wisconsin

6.85%

6.80%

13.65%

Wyoming

9.38%

8.25%

17.63%

* For consistency, we use NCTQ’s data and definition here -- these rates are actuarially–required contributions (ARC), which may differ from what employers do in fact contribute. Several states also have legacy costs associated with closed pension plans: Alaska, Indiana, Oregon, Utah, and Washington. These states are paying down debts associated with inactive plans. Finally, Michigan and Nevada did not report the normal costs in their most recent valuation reports. For these states, NCTQ uses the same rates that were reported for 2014.

When they signed-up, teachers were promised a pension when they retire. It was part of the deal. But since states have long-ignored their fiscal obligations, pension funds carry significant unfunded liabilities, threatening their ability to fund teachers’ retirement. It makes sense that teachers, and particularly their unions, want to fight back.

But is fighting to protect the existing pension plans in perpetuity the right thing to do?

On Saturday at the National Education Association’s (NEA) Leadership Summit, John Jensen, the Vice President of the Retired Executive Council of the NEA, will lead a break-out session on the “bogus” research attacking teacher pensions and how to defend against it. And in the interest of transparency, we, as well as The Laura and John Arnold Foundation (one of our funders), are among Jensen’s list of “faux researchers.”

If his presentation at the Summit last year is any indication, this session will deal less with research and more with ad hominem attacks. But ignoring the evidence will only serve to harm the very teachers he seeks to protect.

There is considerable and growing evidence that 1) at least half of teachers today will not qualify for even a minimum state pension benefit; 2) state pension funds now carry roughly $500 billion in debt and are eating up larger and larger shares of teacher compensation; 3) most teachers would have a more valuable retirement if they participated in a traditional 401k plan; and, 4) today’s teachers, to their own financial detriment, subsidize the pension of currently retired teachers.

Let’s tackle these issues one at a time.

- Nowadays teachers do not spend the whole of their professional lives in schools. In fact, the most common years’ of experience for teachers nationally is around 5 years. This has serious retirement implications. Since the majority of state pension plans have overwhelming amounts of debt, states have raised their vesting periods as a cost savings measure. All of this means that at least half of new teachers will not ever receive a pension. And, when they do leave the classroom it is only with their own contributions (often earning very little interest), and many teachers don’t even earn Social Security during their tenure.

- States are crippled with teacher pension debt. To be clear, this is not teachers’ fault. Rather, states didn’t make sufficient investments and the funds often had lackluster returns. As a result, districts on average now spend $2,500 on employee benefits. And pensions alone comprise over $1,000 of that. This means that – baring a huge reform – teachers today are paying for the pension of current retirees even though they themselves will likely never receive a pension anywhere near as generous when they retire.

- Since most teachers won’t teach for their entire career, a defined contribution plan such as a 401k or 403b would actually produce a more valuable retirement benefit. Due in part to cross-generation subsidization, it takes a 25-year-old teacher decades before her pension is more valuable than her own contributions, or what she could have earned from a DC plan. Pension plans are designed to convey valuable benefits on people who stay in their careers for thirty years or more. And they do. But, they do so at the expense of the majority of teachers.

- Pension funds work kind of like insurance, where one group subsidizes the other. In the case of teacher pensions, the contributions of short-term teachers’ pay for the retirement of longer-term ones. This would be ok if all teachers taught long enough to reach the point when their pension is sufficiently valuable. But that isn’t the case. Instead, short-term teachers incur significant financial losses to pay for pensions that they will never receive. A recent analysis of the massive pension fund in California (CalSTRS), reveals that roughly two-thirds of California’s teachers are pension “losers” because of this. Additionally, newer teachers have the burden of paying for past pension debts.

Despite what the NEA says publicly, the fact is teacher pension systems are in need of reform to better meet teachers’ retirement needs. Shifting to provide new teachers with the option of investing in a 401k for their retirement won’t solve all of the teacher pension woes. The question remains of how will states pay for their existing pension obligations. That will likely take a lot of innovative thinking and some difficult sacrifices from taxpayers, and likely teachers themselves. But to be sure, new teachers shouldn’t have to shoulder the pension costs of retired teachers, particularly when the funds may not be around to support them when they leave the classroom.

- Nowadays teachers do not spend the whole of their professional lives in schools. In fact, the most common years’ of experience for teachers nationally is around 5 years. This has serious retirement implications. Since the majority of state pension plans have overwhelming amounts of debt, states have raised their vesting periods as a cost savings measure. All of this means that at least half of new teachers will not ever receive a pension. And, when they do leave the classroom it is only with their own contributions (often earning very little interest), and many teachers don’t even earn Social Security during their tenure.

Over the last 20 years, per-pupil spending has more than doubled. Alarmingly, however, school district spending on employee benefits grew even more quickly. Now, over 22 percent of per pupil spending goes toward benefits payments. In other words, on average 20 cents of every dollar a district spends goes to teacher pensions and other benefit obligations.

As shown in the graph below, the average district per-pupil expenditure on benefits increased from $763, or approximately 15 percent of all spending in 1992 to $2,524, or 22.9 percent of district spending in 2014. The increased district spending on employee benefits eats away at teacher salaries and other education investments.

The current structure of teacher pensions are responsible for a lot of the increased spending on employee benefits. In fact, over $1,000 per pupil is spent nationally on teacher pensions. States, and to a lesser extent districts, have spent decades kicking the can on their pension obligations. And as a result many pension funds now carry billions of dollars in unfunded liabilities forcing them to allocate more money to pay off their debts. Without a corresponding increase in the overall education budget this necessarily means that benefits eat away at other education spending.

Taxonomy:Should public charter schools be allowed to opt out of state-run teacher pension plans?

There are strong arguments in favor of letting charter schools opt out. Most charter school teachers would be better off in more portable retirement plans. And charter schools tend to be new, so it might be unfair to ask them to pay off the debts of the old system.

Still, if charters are allowed to opt out, that puts added pressure on traditional school district budgets as they’re forced to take on proportionately larger shares of state pension legacy costs. As the charter sector has grown over time, and as pension debts eat up a larger and larger share of school spending, the charter school pension question has been bubbling up. It’s even played a small role in the debate over the nomination of Betsy DeVos to serve as the U.S. Secretary of Education.

As my colleagues Bonnie O’Keefe, Kaitlin Pennington, and Sara Mead noted earlier this week in their slide deck analyzing the education landscape in Michigan, DeVos’ home state of Michigan has one of the nation’s largest charter sectors, with more than 40 charter school authorizers and 10 percent of its students attending charter schools. Michigan’s charter school sector is also unique in that 71 percent of its charters are run by an Education Management Organization (EMO), which is a for-profit operator of public schools.

Although DeVos has been personally maligned for Michigan’s large for-profit charter sector, one thing that’s been missing from the debate is that Michigan’s EMOs are exempt from the state teacher pension fund. That means Michigan’s EMOs get to avoid paying a share of the state’s pension legacy costs, and in the process, they’re playing a small part in exacerbating the pension debt problem for all other Michigan public schools.

How big of a problem is this? In order to separate fact from fiction, here are six things to know about charter schools and teacher pensions nationwide, with Michigan as an example:

- Most charter schools already participate in state teacher pension plans. In the majority of states with charter school laws, charters are required to participate and, consequently, they’re paying a share of pension debt costs. In Michigan, all the nonprofit charter schools participate, while the EMOs do not.

- Most charter school teachers who do participate in state pension plans are getting a raw deal. They’re paying for debt costs that they did not create, in a retirement system from which they won’t benefit. Those charter school teachers, including those working in nonprofit charters in Michigan, should be asking why they’re being forced into such a system when they could have something that better meets their needs (see here for examples).

- Even in voluntary states, charter participation varies widely. A 2011 report for the Fordham Institute found that, of the 16 states that allowed charter schools to choose whether or not to participate in the state pension plan, participation ranged from 23 percent in Florida to 91 percent in California.

- Pension contributions are determined on a statewide basis. We’re talking about state pension debt here. Just because the charter sector grows in any given city does not mean it will dramatically alter the dynamics of an entire state’s pension plan. Looked at from the statewide perspective, charter school market share is still relatively small. For example, it doesn’t really matter for pension contributions that charters enroll 53 percent of the students in the city of Detroit. Michigan runs a statewide teacher pension plan, so what matters is that approximately 7 percent of students statewide are enrolled in EMOs that do not participate in the pension plan.

- Traditional public schools do face higher contributions when charters opt out of state pension plans, but those costs pale in comparison to overall state pension debts. In Michigan, for example, participating school districts are required to pay 13.9 percent of each teacher’s salary toward unfunded pension liabilities. If Michigan forced EMOs into the system, that would broaden the total payroll base in the pension plan by roughly 7 percent*, meaning the contribution rate could also fall 7 percent, to 12.9 percent of salary. But consider this in perspective. Michigan’s contributions towards its unfunded liabilities have increased 143 percent over the last 10 years. The state’s charter sector has played only a tiny role in that increase.

- Charters may be an easy target, but they are not the cause of, nor the solution to, state pension debts. Although states vary in how they plan to pay off their pension debts — whether the money is coming out of state or district budgets — all states calculate their debts as a percentage of teacher salary.** That is, states think of their pension debt obligations as a percentage of the total salary base of all members of the plan (mostly teachers but other district staff may be included as well). This arrangement is sensitive to the number of employees in the system and the salaries they earn. Pension debts must be spread over fewer workers if a recession hits and districts hire fewer teachers, if charters expand and are allowed to opt out, or simply if school enrollment declines due to demographic factors.

In this case, the problem is not charter schools, it’s the fact that states accrued large pension debts and are using an unfair funding mechanism to pay them off. Unfunded pension liabilities were not caused by students or teachers, and legislators should not expect schools to bear their full burden. Given that state politicians caused these problems, the states —not school districts, and certainly not charter schools — should bear the budgetary burden of fixing them.

*I’m making some broad assumptions here about student/teacher ratios and salaries in Michigan’s EMOs, but given national data, I think these estimates are probably conservative on the high side.

**Some state governments take full responsibility for teacher pension plans, other pass all the costs on to local school districts, while others split the responsibility between state and local governments. Each of those options carries a different set of incentives. Those incentives are worth a separate discussion, but they’re not the subject of this piece.

Back in 2014, we wrote about California Governor Jerry Brown’s plan to increase teacher, district and state contributions to the state teacher pension fund. The California State Teachers Retirement System (CalSTRS) was facing a staggering $74 billion unfunded liability, accrued over years of over-promises and lower-than-expected returns. At the time, we commended Governor Brown for taking preemptive measures to pay down those debts.

As the plan ramps up, it’s beginning to take a toll on district budgets, and it’s worth revisiting what was in that plan. Under Gov. Brown’s proposal, teacher, district, and the state pension contributions will ramp up such that, by 2021, 38 percent of each teacher’s salary will be going directly into the pension system. Districts will bear the brunt of this burden. Their costs will jump from paying 8.25 percent of each teacher’s salary in 2014 up to 19.1 percent in 2021.

The effects of Gov. Brown’s plan are starting to be felt in districts across the state. Earlier this month, San Diego Unified School District announced major, pension-induced budget cuts. Voice of San Diego showed the district had paid $75.7 million toward CalSTRS contributions in 2014. This year, with the contribution percentage jumping to 12.58%, the cost is nearly $124 million, and SDUSD is feeling the squeeze. They’re not alone. As districts take on the majority of the contribution increases, money that could otherwise go toward raising teacher salaries, combating teacher shortages, hiring classroom aides, or expanding pre-k will instead go to paying down the state’s pension debt. Over time, districts may get less money from the state as well, as the state’s share of the contributions also ramps up.

At the same time, teachers may feel frustrated. They may not know that district contributions are going up; after all, those contributions don’t show up on their paystubs, even if they are real costs born by their employer. Yet, teachers’ own contributions went up as well, and those are already showing up as lower take-home pay.

Perhaps worst of all, most of the new money is going to pay down pension debts, not to fund actual teacher retirement benefits. Most California teachers will never see a benefit from their pension system and are simply subsidizing past debts and the retirements of very long-term veterans.

Existing legislation ensures these district contributions will continue to rise through at least 2021. This is better than ignoring the mounting debt, but it will dramatically hinder school in their ability to serve teachers and kids. Instead, California teachers may want a refund.

Taxonomy: