Collectively, states face $1.4 trillion in unfunded pension liabilities, and $500 billion of that is due to teacher pension debt. As much as we here at Teacherpensions.org would like to shift the conversation to whether or not those pension plans are providing adequate retirement security to all teachers—they generally are not—the reality is that state legislators are much more focused on these large budgetary pressures than they are on retirement benefits for individual teachers.

Annually, states are contributing roughly $37 billion* a year just to pay off teacher pension debts, and those pension debts can’t just be wished away. So, what are the choices states face in dealing with those large pension debts? I see at least six options:

1. Wait and see. This is the approach most states are taking. They’re essentially hoping that stock market returns will surpass their assumptions and allow their investments to grow enough to wipe away their debt. This hope isn’t without precedent. Around 2000, at the end of the dot-com boom in the 1990s, the typical pension plan was fully funded (see Figure A here). Unfortunately, state legislators acted as if those market returns were the norm, and they proceeded to dramatically cut contributions and enhance employee benefits retroactively.

Those decisions turned out very badly, and I suspect states are making similarly short-sighted mistakes today. Remember, the $500 billion figure above already assumes states are able to hit their investment rate targets of 7.5 or 8 percent a year. States need to hit those targets every year or else their debt piles will grow even more. Basically no credible analyst thinks this is possible anytime soon, but states will continue to hope they can miraculously escape the pain.

The downside of the wait-and-see approach should be obvious. States and school districts are already dedicating increasing shares of their budgets toward pensions, and any stock market crash, or even just a few years of mediocre returns, will only accelerate that trend. Plus, as plans have increased in size, they’ve become even more susceptible to large swings in the stock market.

2. Restructure the debt. This is another common choice for states. Rather than dealing with the debt, they might just change the time period for when they have to pay it off. Imagine you have a 30-year mortgage on your house. After a couple years, you decide that you can’t meet the full monthly payments, so you take out a 30-year loan on those monthly payments as well. This may sound crazy, but some states do this automatically every year, while others revisit their decisions every couple years and promise to really, seriously, finally, make their payments this time. Generations of politicians have all made the same promises.

3. Cut benefits. State pension debts are promises to retirees, and it might be tempting for some state leaders to try to trim the debt by cutting those promises. That could involve anything from reducing cost-of-living adjustments given to retirees or altering the formula for current workers. While these approaches could lead to large cost savings, and there are some approaches that would only affect teachers with many more years left in the profession, as a general rule I would caution states against cutting benefits. There's big financial gain, but large potential downsides in terms of political, legal, and moral backlash.

4. Offer pension buy-outs. Another way to reduce pension liabilities is to get people to voluntarily opt out of them. By offering upfront cash payments, states may be able to induce some teachers to switch from the current defined benefit plan, with large and unpredictable debt costs, to more predictable defined contribution plans. When presented with such a choice, we don’t know if teachers would make smart financial decisions, or if there might be some perverse incentives for people who take up the buy-out offers, but judging by places that have tried similar efforts, there might be large portions of teachers who would prefer upfront cash payouts over long-term pension promises.

5. Issue bonds. State pension debt is flexible, and legislators have a tendency to shirk their long-term pension funding responsibilities in favor of other, more immediate spending priorities. That pattern has led us to where we are today, where states have over-promised and under-saved. States could decide to commit themselves to a more tangible payment schedule by issuing “pension obligation bonds.” Bonds would force states to make regular payments, and, in theory, they offer the state a way to reduce their obligations. After issuing bonds paying interest at, say, 5 percent, they would invest the proceeds and hope that they could earn a higher rate of return over the life of the bond.

The theory behind pension obligation bonds hasn’t always worked, especially over shorter time periods, when returns can be more volatile. States have used pension obligation bonds as a way to escape temporary budget problems, but the basic problems resurface if the state isn’t disciplined enough to continue making pension contributions. And with the stock market around all-time highs, now might not be the best time to invest billions of dollars in new money.

6. Find new revenue. This is perhaps the best option, but I haven’t seen many states try it (with some exceptions). There are lots of choices here, though. My personal preferences would be for states to impose a new consumption tax on something that’s bad for the world, like gambling or carbon emissions or sugar or cigarettes, but states could also impose a special tax on millionaires or rent out some state asset (like highways or parking lots). The specific solutions would vary by the state, but the important thing would be finding a new source of revenue to pay off pension debts.

There are better and worse choices on this list, and states could choose to pursue more than one of them at a time, but regardless of which path a state chooses, none of them are permanent solutions unless they’re also paired with broader structural changes that close existing defined benefit pension plans to new members. In return for their (higher) contributions, it seems reasonable for taxpayers to insist that the state come up with a reasonable plan to prevent the state from accruing these debts ever again.

Unfortunately, most state leaders are letting their debts prevent reforms that would be good for teachers. Instead, they’re using the new generation of teachers to pay off past debts. That’s not fair, and it’s not the way pensions are supposed to work, but that’s the bet most states are making today.

Ideally, states would adopt a package of reforms that accomplished three things simultaneously—pay down existing debts, prevent the state from accruing similar debts in the future, and provide all teachers with adequate retirement savings. That sort of bargain would provide relief to taxpayers, give confidence to existing teachers and retirees that their benefits are safe, and put all new workers on a path to a secure retirement.

*To get the estimate of $37 billion, I took the $313.4 billion schools and districts are spending on salaries and multiplied it by the 12 percent of salary the average state is spending on pension debt costs. That’s not a perfect estimate because the pension costs quoted here represent a state average, not the average across all teachers nationwide, but it’s a reasonable approximation.

The conventional wisdom on saving for retirement offers two key principles. First, you should start saving early. And second, the wealth of your savings is directly related to how much you contribute to them. In fact, these two ideas form the basis of a Prudential commercial that frequently runs on TV.

For people in most professions the conventional wisdom more or less applies. But, unfortunately, it doesn’t for public school teachers. That is because nine out of ten teachers are enrolled in defined benefit plans that accrue benefits differently, based on state-determined formulas that multiply a teacher’s final salary by her years of experience.

A recent study from the University of Arkansas found that, in the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS), nearly two-thirds of entrants into the teaching profession are pension losers. That is, the majority of California teachers will either be ineligible for a pension or the pension they do qualify for is not worth as much as the money they themselves contributed to the overall pension fund.

This happens because most of the teacher’s own contributions, and the contributions made by the state on her behalf, actually subsidize the pension of more veteran teachers. It’s not until teachers stay in the classroom for a very long period when the value of her pension finally surpasses the value of the contributions.

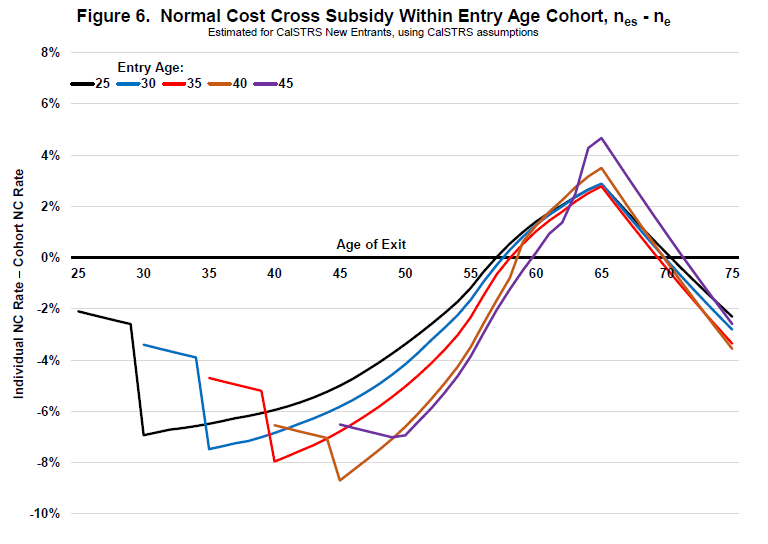

The graph below illustrates the value of a teacher’s benefit (what pension plans refer to as the “normal cost” of benefits) broken down by entry age and longevity. It shows that less experienced teachers provide a considerable subsidy for those teachers who last in the profession longer. This pattern holds regardless of the teacher’s age when she enters the profession, although teachers who begin their careers at later ages earn a positive benefit after fewer years of working. Note that California teachers technically qualify for some pension after only 5 years, but even reaching that milestone does not protect against many more years of teachers cross-subsidizing more experienced veterans.

Source: Robert Costrell and Josh McGee, “Cross-Subsidization of Teacher Pension Normal Cost: The Case of CalSTRS,” University of Arkansas College of Education & Health Professions, October 24, 2016.

This happens because how much a teacher puts into the pension system does not determine how much she gets out. As a result, teachers do not qualify for much in the way of pension benefits until late in their careers, as they near retirement age. Thus, state pension systems (as illustrated above) are extremely back loaded and shorter-term teachers are subsidizing the retirement of teachers who stay their full careers.

This cross-subsidization presents a number of problems. The system lacks transparency, and teachers may not realize how much is being contributed on their behalf or how the system creates these cross-subsidies. The system overall may look “cheap,” but it might be obscuring the fact that some portion of teachers will receive quite adequate benefits, while most teachers get much less. Also, the problem of cross-subsidies is compounded over time as teachers enter and leave the profession, contributing to cross-generational pension liability problems. And perhaps the biggest problem is that more than half of teachers are “pension losers” whose pensions have been compromised by this back-loaded cross-subsidized system.

Defined contribution plans such as a 401k or 403b account don’t have these problems. Under those types of plane, a worker’s retirement benefit is directly related to how much the employer and employee contribute to it, and how much those contributions grow over time. Those types of plans also avoid the problem of back-loading and therefore employees do not, in effect, have their retirement savings diminished if they leave the profession before reaching retirement age.

The graph below illustrates the value growth of multiple kinds of retirement plans. The data assumes a teacher who entered the workforce when she was 25. It’s clear from this graph that the retirement savings of the majority of teachers today would benefit considerably if their state offered a DC or a cash balance (CB) plan instead of their traditional pension. In fact, the DC plan provides a teacher with greater retirement wealth except for the very few teachers who spend their entire career in the classroom in the same state.

Source: Nari Rhee and William B. Fornia, “Are California Teachers Better off with a Pension or a 401(k)?,” UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education, 2016, available at: http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/are-california-teachers-better-off-with-a-pension-or-a-401k/.

To better serve teachers’ retirement needs, states should at least provide newly hired teachers with the option to avoid the traditional state pension system, instead choosing a more portable defined contribution plan. This would be better for teachers and help keep states from continuing to add to their burgeoning unfunded pension liabilities.

Taxonomy:- As we close out 2016, the major events of this year will likely shape the policy conversations around public retirement for years to come. We've collected a highlight reel of teacher pension posts to capture the year's developments. Our most popular posts of 2016 are below.ResourcesPeople are curious; our top source of incoming traffic are readers who want to know how public pension issues affect them and their communities. Our most-read content consistently features pension resources, fact sheets, and maps that break up pension data by state.

- What Is the Average Teacher Pension in My State? The title here is about as straight forward as it can get. Interested in data on the average teacher pension in your state? See this post, but be sure to take into account the caveats around the "average" pension.

- How Does Your State's Pension Plan Compare? An Updated List of Pension Resources The resources here are designed to help teachers, reporters, policymakers, or anyone interested in learning more about teacher pensions in their state. Wondering where to find more information on a particular state’s pension debt? What about a particular state or municipalities’ pension plan? This post is your go-to resource.

- Map: The "Average" Pension of Retired State and Local Government Workers, by State What does the "average" retired state or local government worker receive in pension benefits? There's a map for that. The data here comes from the U.S. Census Bureau, and it shows the statistical mean pension benefit paid out in each state. Average pension benefits tend to be highest in the Northeast and in Ohio, Illinois, Colorado, Nevada, and California. Benefits tend to be more modest in the Bible Belt and the Northern Rockies States of the Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho.

- 10 States Spend More on Employee Retirement Costs Than on Higher Education We've watched pensions devour state and local education budgets, eating up dollars that could be spent on other public services. This post digs into the ways in which higher education is uniquely harmed by rising pension costs.

Teacher-FocusedCurrent state pension plans do not provide the majority of the teaching workforce with a secure retirement. Newly hired teachers lack portable, fair, or secure retirement plans, while effective veterans can feel financial pressure to leave the classroom sooner than they'd like.- A Tale of Two Teachers: A Retirement Story Here, we compare two teachers with different start dates. In every state, a teacher's pension amount is based on her final salary in the last year she worked, regardless of when that happened to be. In this way, pensions reward later-career service much more heavily than early-career service.

- The Pension Pac-Man: Still Eating Away at Teacher Salaries 2016 also brought the release of our report, “The Pension Pac-Man: How Pension Debt Eats Away at Teacher Salaries,” which used data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to show that, like the insatiable Pac-Man, the rapidly rising costs of teacher retirement and insurance benefits are gobbling up funds that could be spent on salaries. Spoiler alert: the trends don't look good.

- What Was Behind the Rise (and Subsequent Fall) in Teacher Turnover? Curious about teacher turnover? We were too. While it may be tempting to blame teacher turnover on current education policies, Chad Aldeman explains how demographics and rising retirement rates offer a more plausible explanation.

- How Many Teachers Deserve Adequate Retirement Benefits? Some? Most? All? Today’s teacher pension systems only provide adequate benefits to teachers with extreme longevity. This post digs into the backloaded structure of most defined benefit retirement plans and argues that all teachers deserve a path to a secure retirement.

Retirement Writ LargeFinally, two of our most popular posts discussed the effect pensions have on broader retirement issues.- Let's Not Kid Ourselves. There Were No "Good Ol' Days" of Retirement Saving We're busting myths left and right in 2016. Here's one more -- there's a common, widespread belief that the shift from defined benefit pension plans to defined contribution plans in the private sector led to a decline in retirement savings. Not true, says Chad Aldeman, and mourning the death of pension plans is longing for a bygone era that never really existed.

- Could Donald Trump Make Social Security Great Again? What woud a 2016 wrap-up be without an election post? While we'll have to wait and see how President-Elect Trump ultimately approaches Social Security, expanding the program to cover all state and local government employees, including all teachers, would provide workers with a baseline of secure, nationally portable retirement benefits.

Still can't get enough? This post, Why Education Advocates Should Care About Pension Reform summarizes our push for bringing teacher pension reform to the forefront of the education policy conversation in 2017 and beyond.Taxonomy: Pennsylvania announced earlier this month that the contribution rate for its teacher pension plan will rise from 30.03 percent of salary last year, to 32.57 percent next year. Although that 33 percent employer contribution rate is already insanely high, it's scheduled to continue rising in the years that follow. By the 2021-22 school year, Pennsylvania school districts will pay 36.4 percent of each teacher's salary into the pension fund.

To be clear, most teachers will never see this money. Most Pennsylvania teachers don't stay long enough to qualify for benefits worth even as much as their own contributions, let alone the state's sizable contributions. The vast majority of the contributions are for debt that the state has accured after years of over-promising and under-saving. Billions of dollars a year must come out of state and district education budgets in order to pay down these debts.

Graphically, Pennsylvania's employer contribution rates look like a roller coaster (see graph below). A scary, painful roller coaster. While teacher contribution rates have increased only a bit, state and district contribution rates are much more volatile. They rose throughout the 1970s and 80s, then the unprecedented stock market boom in the 1990s allowed state pension contribution rates to fall all the way to 1 percent in 2002. Around that same time, pension plan assets looked flush, and so the state enacted a large retroactive benefit increase for teachers and retirees.

Those turned out to be terrible mistakes based on flawed assumptions. First the dot-com bubble burst, and then the Great Recession hit, and now Pennsylavania's teachers, schools, and taxpayers are paying the price.

Where will this roller coaster go next? Advocates of the current system suggest a wait-and-see approach. They argue that the state can't afford to get off, because the pension plan needs new money from new teachers.

It's true that Pennsylvania can't just pretend it never created this roller coaster. The unfunded pension liabilities are real and aren't going away. In fact, they'll remain even if the state hits its assumed investment target of 7.5 percent, and they'll grow if the state fails to hit that target. Meanwhile, it's not good for Pennsylvania's current or future teachers to ask them to pay down the pension debts through what is, essentially, a tax on their labor.

Instead, Pennsylvania should recognize that its pension debts were created by past state legislatures and governors, and the entire state should carry the burden of paying those off. That could involve other, dedicated sources of revenue, but it's unfair to keep forcing new teachers into an expensive, volatile, fundamentally flawed retirement plan. Pennsylvania can't afford to keep riding this particular roller coaster, and it nees to find a responsible way to shut it down.

Taxonomy:Glass ceilings aren't limited to the workplace, unfortunately. Because most states offer teacher retirement benefits based on their salary, states are extending the gender wage gap into retirement. Here's how.

The majority of teachers (76 percent) are female. The majority of superintendents (about 75 percent), however, are male. A recent Education Week piece dives into the reasoning behind this discrepancy, but rather than dig into the barriers female school leaders face, let's look specifically at the retirement issue.

Most states enroll all educators--teachers, principals, and superintendents--into one state pension plan, and it's usually named the "teacher" plan. But the largest payouts from "teacher" pension systems aren't actually going to teachers, the majority of which are female. Instead, the biggest winners are long-serving, highly paid administrators, who are predominantly male.

In 2014, we covered the release of the Empire Center's New York state pension database; the site lists the pension and services years of every current recipient. We found that, despite its name, the New York State Teachers' Retirement System (NYSTRS) writes its largest pension checks to administrators -- not teachers. In 2014, 14 out of the 15 highest retirement payments (ranging from $220,000 to more than $300,000 per year) went to former superintendents. The remaining top spot went to a research professor. Not one of the 15 retired as a school teacher, and all but one were men.

Not much has changed in 2016. Using the updated database, we examined the top 15 pensioners and found that 14 of them are former superintendents -- that research professor is still the lone standout. Two more women joined the mix though, bringing our total to three out of 15.

The NYSTRS benefit calculations explain why administrators are so heavily favored. NYSTRS maximum benefits are calculated using the following formula: Pension Factor x Age Factor (if applicable) x Final Average Salary = Maximum Annual Pension. The pension factor represents years of service, the age factor allows for a possible reduction should a member choose to retire early, and the final average salary is derived from a member's highest three or five consecutive school year salaries, depending on when he or she enrolled. Administrators (who are disproportinately male) out earn teachers; their average final salaries are much higher, leaving them ahead not only during their working years, but into retirement as well. The predominantly female teacher workforce is paying into the same system -- but getting far less. And unlike a system like Social Security, which awards lower-paid workers with proportionately higher retirement benefits, teacher pension systems include no such protections.

The chart below shows NYSTRS's gender breakdown. There are 204,184 actively enrolled females versus 63,351 men. Additionally, there are about twice as many female retirees as males, suggesting that males may be more likely to eventually draw any pension at all. But while the system is comprised mostly of female members, the system's biggest beneficiaries are overwhelmingly male.

New York's gender discrepancies are a product of the state's pension plan, not some fluke. They are simply one byproduct of a system that creates a small group of pension winners at the expense of the majority of employees who lose out under pension systems -- in New York, 60 percent of new teachers will not qualify for any pension at all (let alone a generous one). Pensions are often billed as especially beneficial to women -- and, if a teacher were to spend the entirety of her career, 25-30 years, in the same system, she would earn a comfortable retirement. But we know that this isn't the case for the majority of teachers. All teachers, especially those who have been historically underpaid, deserve a fair, portable retirement plan.Nearly 100 years ago, states created teacher pension plans that were designed to serve a particular group of educators, especially women, who never married or had children. The publicly-funded systems were justified as protection for women who had taught for their full professional career, who likely didn’t have much in the way of personal retirement savings and would otherwise go without retirement support.

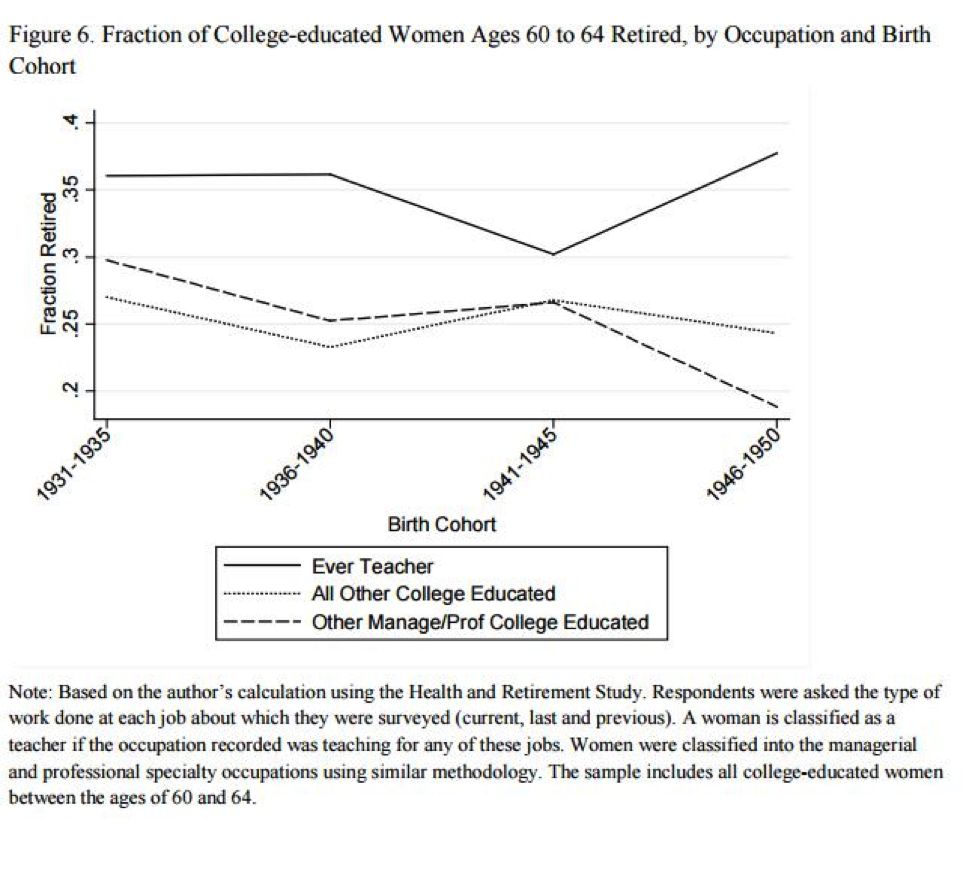

Pensions have evolved somewhat over time, but they’ve never escaped this original intent. Today, pensions provide financial security for those teachers that stay in the profession, but they also quietly push out veteran teachers. These leaders may have more to give to the classroom, but they are financially penalized for doing so. In a new paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research, Maria Fitzpatrick suggests those incentive structures may be having an impact on women's retirement rates more broadly.

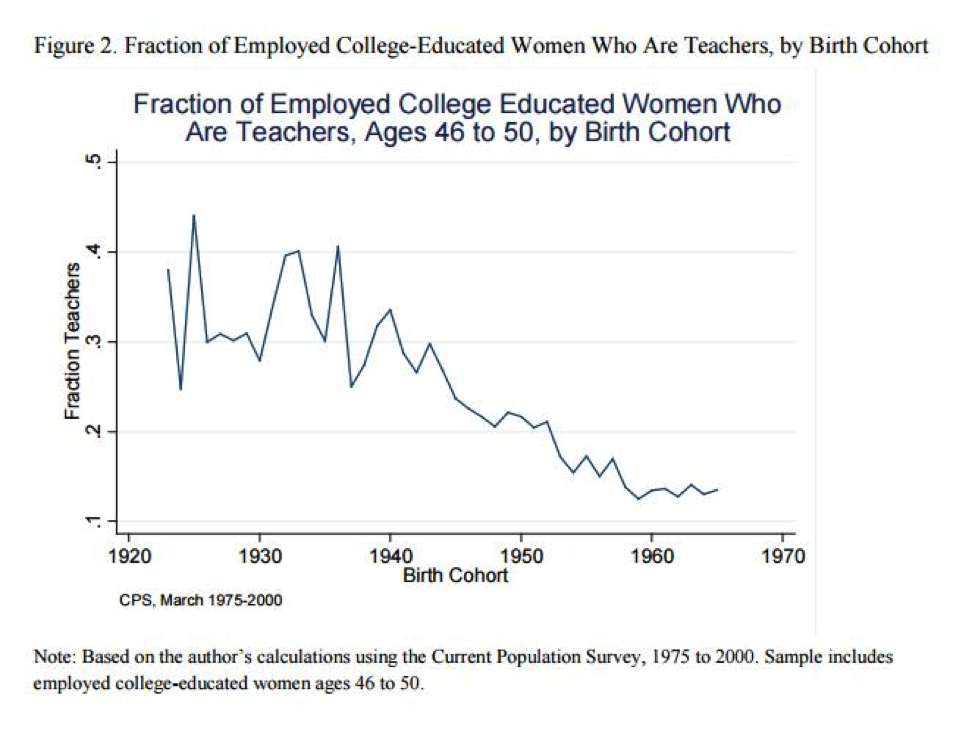

Fitzgerald found that between 2000 and 2010, labor force participation rates of college-educated women between the ages of 60 and 64 jumped 20 percent. At the same time, as shown in the figure below, a lower proportion of these college-educated women were ever teachers. Fitzgerald’s paper suggests this is because fewer college-educated women are becoming teachers.

This has several implications. One, it’s a tangible sign that college-educated women have more career options than they did in the past. Whereas 30-40 percent of college-educated women born in the first part of the 20th century became teachers, today that figure is closer to 15 percent. The expansion of opportunities for women is undoubtedly a good thing, no question, but it also meant a smaller potential labor pool for schools.

Two, because 90 percent of teachers are enrolled in defined benefit pension plans that push out veteran teachers, these demographic trends have widened the gap in retirement ages. Figure 6 from Fitzpatrick’s paper shows that female teachers are exiting the workforce sooner than their non-teaching peers. Fitzpatrick argues that this is linked to teachers’ participation in defined benefit pension plans, which encourage retirement at ages earlier than Social Security. That disconnect, where teachers have earlier retirement ages and longer retirement periods, has broader societal and cost implications.

So what does this mean? Recent National Center for Education Statistics data show that retirement security is a driving factor in teachers’ career decisions. So much so, in fact, that the ability to maintain teacher retirement benefits ranked above salary, class size, and child care availability in teachers who had left the classroom’s decisions to return. Effective, veteran teachers deserve fair retirement savings plans that continue to grow in value, rather than arbitrarily peaking and plummeting at a set age. Pensions aren’t keeping up with a changing society.Taxonomy: