At the end of April a Cook County judge dismissed a lawsuit brought by Chicago Public Schools against Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner. CPS alleged that both the state school funding formula and the teacher pensions system are unconstitutional because they lead to the systematic underfunding of the education of low-income students and students of color.

While Judge Franklin Valderrama recognized that the state’s school finance system is broken, he nevertheless dismissed the case. Plaintiffs do have the opportunity, however, to refile by May 26.

This puts CPS right back where it was when the suit was filed: facing a massive budget deficit that may force the district to end the school year weeks early. Unable to pay its bills, the state legislature passed a bill late last year allocating over $215 million to help CPS keep schools open for the full year.

The problem is that Governor Rauner vetoed the bill. He refused to send the necessary emergency funds to Chicago to alleviate a problem – one the state helped to create – without first winning significant reforms to the teacher pension system. In effect, Governor Rauner is holding Chicago students hostage. He is leveraging roughly 3-weeks of education for hundreds of thousands of students in exchange for pension reforms.

To be clear, the state’s finances are an unmitigated disaster and in desperate need of reform. But, the ends do not justify the means. Coercing the legislature to reform pensions by threatening harm to Chicago’s students smacks of extortion. But the gambit may be paying off for Gov. Rauner. The legislature is currently considering a bill to reform teacher pensions that may appease the governor and encourage him to release the millions for CPS.

There is a worry that the Speaker of the House, Michael Madigan, who himself hails from Chicago, will derail the process. Some view Madigan as a longstanding obstacle to important reforms in CPS. That view may be right in this instance. But the strategy of using students as a bargaining chip likely strengthened Madigan’s position.

Consider the recent example from Pennsylvania, the former Governor of Pennsylvania, Tom Corbett unsuccessfully employed a similar approach by withholding roughly $50 million from Philadelphia School District without concessions from the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers. Governor Rauner may find a similar outcome here: threatening students is a poor political strategy.

The financial woes facing Chicago Public Schools are considerable. Fixing them requires compromise on both sides. But bargaining with students’ education is a recipe for disaster and may make reform even more difficult.

Taxonomy:Giving teachers a say over their retirement plan just might be good for everyone.

The majority of states enroll their public school teachers in defined benefit (DB) pension plans. These plans are back-loaded, and they mainly benefit the small portion of teachers who remain both in the classroom and in the same state for 20 years or more. Supporters of these plans argue pensions are a retention tool – teachers might be less likely to leave the profession if there’s a large financial incentive waiting for them if they stay. These advocates rarely acknowledge that this idea suggests it's ok to use someone's retirement security as a tool to shape their behavior, but it's worth investigating whether these claims play out in pratice. That is, does a teacher's retirement plan shape her behavior?

My colleague Chad Aldeman has a forthcoming piece on this question in Education Next, but a recent study published by the National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER) provides some initial answers. The study, authored by Dan Goldhaber, Cyrus Grout, and Kristian Holden, looked at what happened when Washington State switched from a pure DB system to a hybrid plan. Hybrid plans combine aspects from portable, defined contribution (DC) models, like 401(k)s, as well as traditional, defined benefit plans, like most pensions. Here’s how it worked:

Washington introduced their current hybrid plan (called TRS3) in 1995, to replace their existing DB plan (TRS2). At the time, existing employees remained in the original DB plan, while new hires were enrolled in the new hybrid plan. A two-year transfer period allowed teachers in the DB plan the option to switch into the hybrid plan – those who did so received a bonus payment equal to 65% of their accrued TRS2 contributions.

In 2007, Washington made changes again. Teachers hired after that point can select either the DB plan or the hybrid plan, with the latter as the default option for those who do not make an affirmative selection. The table below shows the differences between the two plans:

Public Pension Reform and Teacher Turnover: Evidence from Washington State 2015

So what happened to teacher retention after Washington changed its retirement plan? The study compares three sets of teacher turnover rates:

1. Teachers hired just before and after the introduction of the hybrid plan

2. Teachers who could choose between the DB or hybrid plan as new hires

3. Teachers who could transfer from the DB plan to the hybrid plan

In all three of these situations, proponents of pensions as retirement incentives would expect higher turnover rates from those teachers enrolled in TRS3, the hybrid plan. In this plan, overall compensation is less back-loaded, which decreases the monetary incentive for teachers to stick it out for a big payout at retirement.

In the first two comparisons, there was no systemic difference in turnover patterns between the two groups. The last comparison though, examining those teachers who transferred from the DB pension plan to the DC hybrid plan does show a relationship between pension structure and teacher turnover. But instead of turnover increasing with a portable plan, it actually decreased. From 1998-2005, teachers who transferred into the hybrid plan actually had turnover rates that were 1-4 percentage points lower than those who remained in the DB plan. The authors hypothesized that perhaps giving teachers a choice made teaching more attractive.

Overall, this study presents additional evidence that teachers simply aren’t that sensitive to pension plan design. Further, in another paper from Goldhaber and Grout, they found that Washington’s hybrid plan did not harm teacher quality or retirement security. In practice, the pensions-as-retention-strategy talking point doesn't hold up.

Federal data from the National Center on Education Statistics (NCES) offers a potentially surprising revelation: Private school teachers have higher turnover rates than their public school counterparts, and it’s not particularly close.

The data below capture what NCES calls the “leaver” rate. NCES regularly surveys teachers, and it divides respondents into three categories: stayers, movers, and leavers. Stayers are teachers who were teaching in the same school in the current school year as in the base year. Movers are teachers who were still teaching in the current school year, but who had moved to a different school. And the leavers, represented in the graph, are teachers who left the profession entirely.

As the graph shows, the teacher leaver rate is almost twice as high at private schools than it is at public schools. Both have increased over time, but private schools have seen their rates increase even faster. These data call into question many of the common explanations for changes to teacher turnover rates among public school teachers, such as No Child Left Behind, teacher evaluation reforms, or the Common Core. Those reforms, which applied primarily to public schools, simply can't explain the increases in teacher turnover in private schools. (In fact, during the NCLB era, public school teacher turnover did rise a bit, but private school turnover rose even more.)

The next graph shows how the "leaver" rates have changed over time for public and private school teachers, by their years of experience. Over time, private schools have seen dramatic increases in turnover among early-career teachers, whereas in the public sector, early-career teachers are more likely to stay today than they were in the late 1980s. In fact, private school leaver rates have accelerated faster than public school rates for every age group except those with 20 or more years of experience. (As my colleague Chad Aldeman has written, those late-career turnover increases can be traced at least partially to changing demographics and rising retirement rates.)

Source: NCES

Another way to look at this data is to attempt to follow synthetic "cohorts" of teachers over time. We've run this same analysis on public school teachers and found that cumulative retention rates for public school teachers haven't changed that much over time. Regardless of the year they started, about one-third of public school teachers had left within five years, and about half were gone within 10 years.

But compare that finding to private school teachers, where we see a noticable difference across cohorts. Rather than the lines overlapping, signaling similar turnover rates, we see clear gaps across entry years. In the private sector, unlike in public schools, teachers who entered in 1987 had higher retention rates than teachers who were hired in 1990, and so on. Those gaps are smaller in more recent years, but the NCES data suggest that far fewer private school teachers today are making it to key career milestones than did in the past.

Since the cohort graph is somewhat hard to read, see the same data in the table below. Each column represents a starting year, and the rows indicate the cumulative retention rate by years of experience. Private school teachers who leave within three years of experience provide an especially compelling example. Among new private school teachers in 1987, a little over one-quarter had left within three years. In 2008, more than half were gone within the same time frame. Again, these are much higher figures than for public school teachers.

Since this is a pension blog, it's worth mentioning that we do NOT think pensions are the cause of, or solution to, this issue. First, while public sector teachers are more likely to be enrolled in defined benefit pension plans, that disparity existed in the 1980s as well. That is, it can't explain the changes over time, nor can it explain the changes by age group. Second, while pensions could theoretically boost teacher retention, in practice we don't actually see much evidence of that. We don't have plausible theories for why turnover in private schools seems to be rising much faster than it is in public schools--although we'd love to hear suggestions--but as the country considers making additional public investments in private schools, it's worth wondering why these schools are losing so many of their teachers.

Taxonomy:Florida offers its teachers a choice. When they begin working in Florida schools, they can choose to join the state's traditional defined benefit (DB) pension plan, or they can enroll in a portable defined contribution (DC) plan instead. The state has an entire website devoted to helping teachers decide which plan is best for them given their age, how long they plan to stay, and how comfortable they are investing money.

At first glance, Florida seems neutral about which option teachers choose. When I took the quiz to identify which plan would be better for me, it recommended the portable DC plan and reassured me that there were a range of investing options, even for people who weren't that confident in their investing abilities. Another state document has a nifty chart estimating which teachers would be better off in which plan, depending on their starting age and how long they planned to stay. It looks like this:

The state's own estimates suggest that anyone who starts teaching in Florida under the age of 45 would be better off in the portable "Investment Plan." Even for people who begin teaching later in life, they would benefit from the DB Pension Plan only if they stayed more than 8 but less than 23 years. So, Florida is essentially telling teachers that there's only a small sliver of teachers for whom the DB Pension Plan would be a better option.

Another document on the Florida Retirement System site includes a footnote that specifically warns teachers that, "According to FRS historical statistics, less than 20% of newly hired employees and 50% of those with over 10 years of service actually stay a full career in FRS employment, given today's mobile society."

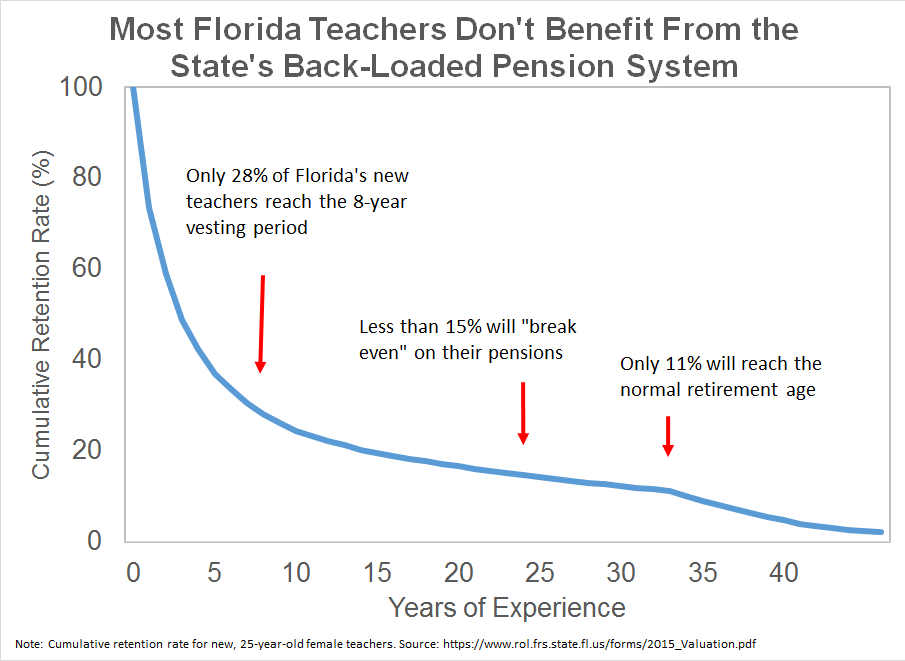

Indeed, this lines up with my own research on Florida's DB plan. Only about one-quarter of new Florida teachers remain in the pension plan for the eight years it takes to qualify for any pension plan at all. A Florida teacher must teach continuously for 24 years before finally qualifying for a pension worth more than her own contributions plus interest. And only about one-in-ten stick around long enough to reach the state's normal retirement age. In short, Florida's defined benefit pension system doesn't work well for the vast majority of its teachers.

Why, then, does Florida default all of its teachers into the defined benefit Pension Plan? (Note: See update below. Florida has since changed its default option.) If teachers do not proactively enroll in a retirement plan within their first five months on the job--a time when many first-year teachers are more worried about the demands of their new job--the state automatically enrolls them in the Pension Plan. To put it another way, Florida defaults all of its rookie teachers into a retirement plan that, as the plan itself acknowledges, is probably not right for most of them.

Now, Florida deserves credit for offering its teachers a choice at all. Alaska is the only state that automatically enrolls all teachers in a portable retirement plan, but five other states in addition to Florida--Michigan, Ohio, South Carolina, Utah, Washington--provide teachers a choice. The rest automatically place all of their teachers into back-loaded defined benefit plans.

But Florida is unlikely to see substantial enrollment changes until it shifts its default. Defaults can be powerful "nudges" that encourage people into behaviors they may not otherwise proactively choose. When companies have switched their retirement plans to automatic participation (with optional opt-outs), they have seen enormous enrollment gains, even though the choices remain the same. These patterns also apply to things like contribution rates and investment choices.

Florida should be applying those lessons to help nudge teachers into better decisions. A bill currently making its way through the state legislature would do just that. It would still give Florida teachers a choice over their retirement plan, but it would set the more portable option as the default. Rookie teachers may not have the time or the wherewhithal to think about their retirement plan, but the state should nonetheless help them make smart decisions.

In the summer of 2017, Florida passed legislation to shift the default option to the portable defined contribution plan, following the recommendations in this post. The new rule applies to all Florida teachers hired after January 1, 2018. For more information, see here.

In an article last week, The New York Times argued that the teacher pension system in Puerto Rico is little more than a legal Ponzi scheme. Virtually all of the contributions made by current teachers go to pay retirees because the system will be bankrupt next year. These younger teachers are paying for other people's retirement, but they can’t count on a pension of their own when they retire.

Simply put, Puerto Rico’s pension system is an accelerated example of pension problems in the rest of the country. Puerto Rico's finances are in even worse shape than the systems in Illinois or New Jersey. The problem of young teachers’ cross-subsidizing retirees at their own expense is even more pronounced there. But the pension crisis in Puerto Rico is where many states are headed if they don’t make reforms now.

Evidence that teacher pension funds have problems is growing. Media coverage of the issues is expanding. Yet, many teachers still are unaware that pension systems are struggling financially and failing to provide most teachers with a good retirement benefit.

In their defense, when I was teaching I was only vaguely aware that I was earning a pension. And to be honest I had no real sense of how the system worked. It turns out that even 30-plus year veteran teachers can be confused by complicated teacher retirement systems.

To help clarify these complicated issues, the Times also published a series of graphics that shed some light on teacher pensions, document the latest research, and explain how many of the current state systems truly fail to provide teachers with a valuable retirement benefit.

Citing research from us here at Bellwether and the Urban Institute, the Times piece provides two graphics demonstrating just how long it takes for teachers in every state to “break even.” For example, it takes teachers in Ohio 35 years of working in the classroom before they break even and earn a pension that is as valuable as their own contributions.

Finally, they show the percent of teachers in each state that will actually ever reach their break even point. It’s not pretty. The majority of states operate teacher pension systems that do not work for the bulk of their teachers.

These problems won’t fix themselves overnight. But, reporting like this will help to elevate the issues, show teachers just how poorly they’re being served, and hopefully lead to important reforms and retirement plans that better meet the needs of all teachers.

The Chicago Board of Education recently sued Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner, claiming that the way Illinois funds its schools violates the state constitution and effectively creates a “separate but unequal” system. And now, due to a massive budget shortfall, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) suggests that they may need to end the school year more than two weeks early.

Beyond the inequity of the school finance system, the lawsuit further alleges that the teacher pension system is also at fault for treating Chicago’s students as “second-class children.”

They’re right.

Over the past few months I have analyzed 10 years’ of Illinois salary data precisely to determine the degree to which Illinois’ and Chicago’s teacher pension system contribute to school funding inequity.

Although we won't release final numbers for a few weeks, the results are alarming.

Statewide, the schools serving the highest concentration of low-income students receive only half of the state average per-pupil expenditure on teacher pensions. And, around 60 percent of those low-income, poorly funded schools are in Chicago. In other words, the teacher pension system is compounding Illinois’ funding issues.

Teacher pension systems compound inequitable school funding for a variety of reasons. In Illinois, the biggest problem is that Chicago operates its own teacher pension system separate and apart from the state fund. In other words, Chicago, which has the highest concentrations of high-poverty schools, receives practically no pension funding from the state. And with fewer resources and a smaller tax base at its disposal, Chicago typically contributes to the fund at an even lower rate than the state. The result is a wide disparity in school funding becomes even wider after accounting for pension spending.

Other factors also contribute to the problem. For example, higher-poverty schools tend to have higher student-teacher ratios. They also have more new teachers (with lower salaries). Many of these younger teachers will leave before qualifying for a pension, and therefore will forfeit their state or district contributions.

While the full findings of my study are still under wraps, the conclusions are clear: teacher pensions exacerbate school funding inequities in Illinois. Until the state fixes its inequitable school funding formula, and the pension plan that amplifies and compounds those inequities, Illinois will continue to funnel less money to the kids who need it the most.