Millennials are an easy target, and it’s easy to assume shifts in worker turnover are the result of this generation’s restlessness. But this is a misconception, and once we examine tenure data by age group and generation it reveals that millennials are merely following a broader downward trend in job tenure. Over the long term, millennials are following similar patterns as the generations that came before them.

First, as with any good myth, there's a kernel of truth. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the median time workers have been with their current employer is 4.6 years, up slightly from ten years ago. This data seems to show that, contrary to popular perception, workers are actually staying in their jobs longer than they were in previous years. The New Yorker’s Mark Gimein recently commented on the increase: “our collective nostalgia misrepresents historical job security so completely that it gets it close to backward.”

But wait, the averages here are misleading us from some bigger, underlying trends. We shouldn't be comparing today's average with yesterday's; we should be looking at how tenure changed for groups of workers at various stages of their careers.

We know that older workers tend to have longer tenures with their current employers than younger workers do. This has been true across generations, so what’s critical is looking at how today’s older workers compare to older workers in the past and how today’s younger workers compare to younger workers in the past. Once we take a closer look and sort the data properly, the data confirms the popular perception: job tenure is indeed declining across all age groups. Rather than being an entirely new phenomenon, the mobility of the millennial generation is best seen as merely one part of a greater downward trend.

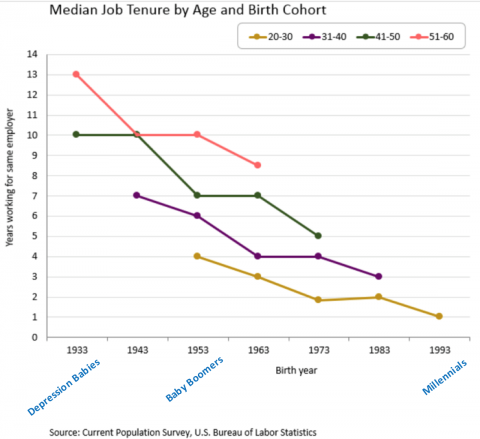

To show this, the Atlanta Fed disaggregated the job tenure data and organized it by age and birth cohort instead of calendar year. Their graph, reproduced below, tells this more accurate story.

When the first group of baby boomers were in their thirties, they had, on average, been with the same employer for about six years. By the time boomers born ten years later reached their thirties, however, they had been with their current employer an average of just four years (see the first two dots on the purple line in the graph). By comparing two groups of workers as they hit the same career milestones, we can see an apples-to-apples comparison of how tenure changes over time.

As the graph shows, the downward trend continued with millennials. When baby boomers were in their 20s, the median boomer had four years of experience with their current employer. Today, the median millennial in his or her 20s has been in their current job for only a year, following a broader societal trend that spans across ages and generations.

It may seem counterintuitive that the median job tenure in all subgroups is declining while the aggregate median is slightly increasing. But that may simply be an artifact in differences in the size of each generation, sometimes referred to as Simpson’s paradox. Today, the baby boom generation is a large force in the labor market, and their size may be distorting the overall trends.

By looking at each generation over time, it’s clear the mobility trend is real, and it’s not a new phenomenon. It has implications in many areas, including how we think about job training, health care, and retirement benefits, not to mention broader societal effects. In order to propose solutions to those problems, however, we must first debunk existing myths and diagnose the problems accurately.

Taxonomy:Chalkbeat Colorado has an excellent rundown of what's happening under Colorado's revamped teacher evaluation law. After two consecutive years of ineffective ratings, tenured teachers (called "non-probationary" in Colorado) lose their tenured status and revert to one-year contracts. The law passed in 2010, but this is the first year any consequences apply. According to Chalkbeat, Denver has 47 teachers, about 2 percent of its workforce, who will lose tenure this year. Among them are 10 teachers with more than 20 years of experience, and another 18 with 15-20 years of experience.

From most angles, this is a good thing. The system had a long roll-out period, and now Colorado schools are finally starting to act as if teacher quality matters. It uses two years of information before making any decisions, and it defers to districts and individual teachers to make the ultimate decisions (the teachers aren't necessarily fired, they just lose their tenured status).

But from a retirement perspective, this puts teachers further at risk, and Colorado already has a risky retirement system. Although the state has very high teacher turnover, Colorado's pension formula really only delivers adequate retirement benefits to teachers who stay for 25, 30, or 35 years. Anyone who leaves before then is left without much in the way of retirement benefits, and would have been better off in a different type of retirement plan.

Colorado has already done the right thing in making the teaching profession at least somewhat contingent on performance. The state should create a retirement system that matches that expectation. Teaching is a difficult profession, and not everyone can do it well, or wants to do it for an entire lifetime. But everyone deserves a secure retirement, and states shouldn't keep retirement plans that assume all teachers can or want to remain teaching for 25 or 30 years.

I could go on, but we've written a whole report on Colorado's teacher pension plan. Read pages 14-18 for some ideas on ways Colorado could modernize its retirement system to match its expectations for teachers.

Taxonomy:Ever wanted to work less and earn more? It’s difficult to pull off, but the majority of teacher pension plans actually incentivize employees to exit at a predetermined age, quietly penalizing those who continue to work. This system deters experienced educators from continuing in the classroom, and recent data suggests it may have negative effects on students, too.

But first, how to account for the drop-off? Teacher pension formulas usually include the following variables: years of service, final average salary, and a benefit multiplier determined by individual states and plans. In the example below, in a state with a 2 percent multiplier, a teacher with 25 years of experience and a final salary of $50,000 would earn an annual benefit of $25,000. Mathematically, it looks this:

These formulas translate into a back-loaded structure where benefits are low for many years until, as teachers near their normal retirement age, their pension wealth accelerates rapidly. While the actual formulas vary state to state, the graph below presents a typical accrual pattern. Early on and up until the midpoint of his career, a teacher’s retirement savings increase only marginally year over year. In fact, in the median state, teachers must work for a minimum of 24 years before their lifetime pension benefits are worth more than their own contributions plus interest. Once they reach that break-even point though, their benefits accrue rapidly. We (and others) have broken this down before. But what happens after teachers reach the pension peak?This gets interesting. The peak in pension wealth usually occurs at the state's pre-determined normal retirement age. In the example above, a teacher reaches normal retirement age at 60 years old. At that point, she is eligible to begin collecting her pension; each year she stays in the classroom, she forgoes a year of pension payment.

We can calculate her annual benefit using our earlier formula. Let’s assume the same 2% benefit multiplier, an average salary now of $65,000, and 35 years of service. Here’s the math on her annual benefit:

.02 * $65,000 * 35 years of service = $45,500 annual benefit

If our teacher retired this school year, her pension plan would begin paying her $45,000 right now. But what if she doesn’t retire? She’s an experienced professional who enjoys her students, and let's say she wants to serve as a mentor to new teachers. She decides to stay another three years, and retires at 63. She now has 38 years of experience*, and her salary has risen a bit now, to $68,000. Here’s her updated annual benefit:

.02 * $68,000 * 38 years of service = $51,680 annual benefit

While her annual benefit has increased by $6,180, she has forgone three years of payments of at least $45,500 – that’s more than $137,000 in total. Even if we ignore the time value of money ($1 today is worth more than $1 in the future), it would take her 22 years to make up the difference. On average, she'd be expected to live 23 more years into retirement, so she'd be making a slim wager that she personally would live longer than average. And remember, she had to work an extra three years compared to her peers! Despite her passion for the profession, it’s in her financial best interests to retire at 60.

This is problematic. On one side, it could encourage teachers who are a few years short of normal retirement age to stick it out in a job they are less than invested in, just to maximize their pension benefits. On the other end, the peak pushes effective veteran teachers who enjoy their work to leave early, lest they lose money.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this pull and push on veteran teachers has an impact on students. A new report from the Manhattan Institute suggests that switching a school system’s retirement offering from lumpy, traditional pension plans to a plan with a steadier accrual would likely increase the number of late-career teachers that postpone retirement. This, in turn, would increase the school system’s total teacher experience level, and, ultimately, the school system’s total teacher quality. Not only would teachers benefit from a better retirement system, but kids would too.

*Some states cap the number of years teachers can claim for pension purposes, but let's ignore those for now, because they would make this situation even worse.

Recently Hillary Clinton, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, outlined her education platform to thousands of educators at the 158th annual National Education Association Representative Assembly in Washington, DC. Her broad priorities include: universal pre-K, elevating the teaching profession, and raising teacher salaries.

Music to teachers’ ears.

But there’s more! Buried in Clinton’s wonkier policy plans, there is another proposal that should also get teachers excited: improving employee benefits.

As a part of her Initiative on Technology & Innovation, Clinton proposes that the government ensure that employee benefits are “flexible, portable, and comprehensive.” She argues that strong benefits that workers can take with them whenever they move and that can be customized to meet their specific needs are essential to a 21st century workforce.

For teachers, improving their benefits – particularly retirement benefits – is long overdue. As has been the case for decades, almost every teacher is enrolled in a defined benefit (DB) pension plan. The idea was that teachers would accept lower salaries when working with the promise of a healthy pension when they retire. Although that model may have worked in an earlier era, today only half of teachers will actually leave the profession with a pension. Another large group of teachers will stay long to qualify for some pension, but it will be meager. In short, teacher pension plans are in desperate need of a redesign.

Clinton’s proposal rightly points out a few ways that teacher retirement benefits could be improved:

Teachers need more flexibility in their retirement plans. In half the states it would take a teacher at least 25 years for him or her to break even and have a pension with a value greater than the amount of money the teacher put into it. In some cases providing more retirement flexibility could mean allowing teachers to opt into a well-designed defined contribution (DC) 401(k) plan. In general these plans would provide greater retirement wealth for most teachers, except for those who teach from an early age and continuously in one state for perhaps 30 years. Alternatively, states could implement a hybrid program with both DB and DC components.

Teachers need portable retirement benefits. Most teacher pensions cannot be carried over state lines, meaning a teacher that moves to a new state will have to start fresh on a new plan. Maintaining multiple pensions can cost a teacher around half of her lifetime pension wealth. Without pension portability, teachers and families who move across the country can face a tremendous financial burden that compromises their retirement savings.

The teacher workforce – like nearly every labor force in America – has evolved considerably. No longer are teachers educators for life, nor do they live in a single state decade after decade. Teachers are mobile. They enter and exit the workforce at different points in their lives. Nevertheless, teacher pension systems have persisted for more than a century with more or less the same structure. By increasing flexibility and portability for teacher retirement benefits, we can ensure that teachers don’t have to choose between working with kids and earning a healthy start on retirement saving.

Taxonomy:- Worried about teacher salaries? You’re in good company. Concerns that American salaries have stagnated span sectors – and, like most economic qualms, those concerns are particularly relevant in an election year. Educators are no different. In her July 5 remarks to the National Education Association, Hillary Clinton told teachers, “we need to be serious about raising your pay…no educator should have to take second and third jobs just to get by.”While Clinton is right to note stagnant teacher pay, policymakers need to think carefully about next steps. We've argued that pensions play a role in eating up budget resources that could be used for teacher salary increases, but there are other trends in the composition of the teaching workforce that may be leading us to the wrong conclusions on teacher wages (and these trends extend beyond education). If our diagnosis is off, our policy solutions may fall short as well.Data from the U.S. Department of Education show average teacher salaries have stalled in the last two decades. The chart below, adjusted for inflation, shows the average teacher makes just $1,791 more in 2009 than in 1989.At first glance, it looks like teacher wages are relatively flat. But what if that isn’t the whole story?The previous graph shows little change in average teacher pay, but that says nothing about individual teachers. Indeed, each individual teacher is paid according to local salary schedules, which tend to give increases as teachers age into the workforce. And, although salary schedules were frozen in many districts in the wake of the last recession, individual teachers continued to move along those schedules and earn annual raises.But average salaries also depend on the distribution of teachers at each step on district salary schedules. If the teacher workforce looked exactly the same today as it did in the past, this wouldn’t matter. But the teacher workforce has changed over time, and teacher experience levels today look dramatically different than what they did 20 or 30 years ago. If you asked a teacher in 1988 how many years of experience he or she had, you’d be most likely to hear 15 years. If you did the same in 2008, the most common answer would have been one year of experience. The numbers have shifted a bit since 2008, partly in response to a fall in teacher hiring in the wake of the last recession, but there are still far more new teachers in the classroom than there were two decades ago.

This shift—from a veteran-dominated profession to one more heavily tilted toward newcomers—also has implications for calculating average teacher salaries. Because veteran teachers earn higher salaries than less experienced teachers, changing teacher experience levels account for some of the stagnation in overall teacher salaries.Even if, like me, you agree with Secretary Clinton that teachers should be paid more, it’s important to understand the forces behind it before devising policy solutions that can solve it.What’s interesting is we may already be past this trend. The teaching workforce, like many other occupations, aged throughout the 1990s and 2000s and is now starting to fall as the Baby Boom generation of teachers retire. As a new crop of teachers age into the workforce, earn higher salaries, and slowly take their place as the dominant group in schools, the trends may reverse, and we may start to see demographics artifically inflating average salaries. No policy would have changed, but our understanding of how well we pay our teachers will have.Taxonomy: With stocks hitting new all-time highs this week, it might be tempting to think pension plans would be celebrating. They're not, for at least a few reasons:

- It's taken too long to get here. Stocks may be at all-time highs, but they are mere percentage points above where they were a year ago. Pension plans assume their investments will return 8 percent year after year. If stocks return less than that mark, pension plans will see their long-term liabilities increase.

- Although the S&P 500 has roughly tripled since its March 2009 low, pension plans still haven't recovered. According to the most recent data from the Center for Retirement Research (CRR) at Boston College, state and local government pension plans have a funded ratio of just 74 percent. That's a tick higher than last year, but it's a far cry from where they were 10 or 20 years ago, and it's still far short of what funds will need to pay future benefit promises.

- Worse, even if pension plans continue to get an 8 percent return every year from now until 2020, the CRR projects funding levels would only rise to 78 percent. That's the best case scenario.

- Attaining an 8 percent investment return going forward is going to be harder and harder. About 25 percent of pension plan assets are invested in bonds, but bond yields are hitting all-time lows and many are actually in negative territory (meaning the bond holder has to pay for the privilege of holding the bond, not the other way around). That puts even more pressure on investments in stocks and private equity and will, in turn, push pension plans into riskier and more volatile assets.

- Who knows what the future will hold, but a wide variety of indicators suggests we may be living in an "everything bubble," where pretty much all assets are expensive based on historical standards. If that does come to pass, pension plans will once again need to cut benefits, raise contributions, or some combination of the two.

Taxonomy: