My colleagues Chad Aldeman and Kirsten Schmitz have written previously about the evolution of teacher retirement plans. They found that even despite recent changes, many state teacher retirement systems are outdated and struggle to provide workers with an adequate benefit that meets the needs of today’s workforce. In fact, teachers have more backloaded retirement benefits than any other group of workers.

Based on our review of teacher retirement plans and a scan of the landscape of retirement programs from public sector employees more broadly, we found 7 states--Colorado, Georgia, Kentucky, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Texas--that offer portable retirement benefits to other state employees that are not available to teachers.

Providing teachers with more portable retirement plans would be beneficial for a number of reasons. For many workers who don't remain in one job for their full career, 401ks and other defined contribution plans often earn greater benefits than a traditional pension. And, these plans are portable and can easily be transferred across state lines. Thus, teachers can change jobs or cross state lines without incurring any losses to their retirement.

Given the benefits to both the employee and the employer, these 7 states should at a minimum extend the portable retirement option to teachers. The systems already exist so the expansion would have no significant administrative expense. Teachers would then have the option of enrolling in a defined contribution or hybrid plan, which would provide them with more flexibility and, in all likelihood, a greater retirement benefit when they leave the profession. States themselves would benefit as well by reducing the number of teachers participating in the state pension system, which are likely already backlogged and strained with large unfunded liabilities.

Fixing all of the problems surrounding state teacher pension funds won’t be easy. But for these states, extending existing retirement options to teachers is a low-cost, high-impact reform that would go a long way toward helping educators earn a better retirement benefit.

Teacher pay and benefits have made headlines over the past few weeks, with walkouts and strikes by teachers in Kentucky, Oklahoma, and West Virginia. A New York Times piece from earlier this week quotes a teacher who likens the movement to a wildfire. Indeed, with so much unfolding so quickly, it can be hard to keep up.

A few publications have simplified/demystified/explained/provided context for what’s happening: EdWeek, the Washington Post, and Fortune have tackled the broad topic of teacher compensation with varying levels of detail. And my colleague Chad Aldeman weighed in on teacher pensions for an NPR panel Tuesday (listen to the show here).

But education issues are heavily state and local; the variances across state lines make high-level discussion of educator benefits especially difficult to tackle in traditional explainer pieces. Teacher retirement benefits, in particular, can be especially complex. Those looking to learn more about the intersection of teacher salaries, teacher pensions, and school budgets may be interested in our additional resources:

- Our simple, 3-minute video explains how teacher pension plans work and how they affect millions of public school teachers.

- Over time, teacher salaries have not kept up with inflation, but total teacher compensation has, due to rapidly rising healthcare and pension costs. Read our "Pension Pac-Man" report for more on the national trends.

- Kentucky teachers (and those in 14 other states) aren’t covered by Social Security. More on that in our explainer video here.

- Want to know what teacher retirement looks like in your state? There’s an interactive map for that.

- Knowing your state’s “average teacher pension” can provide context for larger teacher compensation conversations – this chart captures that, but be sure to account for the listed caveats.

We’re always open for additional questions at teacherpensions@bellwethereducation.org.

This week, thousands of Kentucky teachers marched in the state capitol in response to a prospective change in retirement benefits and general concern with the state budget. While their budget and salary concerns are real, the retirement plan reform is necessary, and will in the long run be good for Kentucky and the state’s next generation of teachers, while still keeping promises to the current workforce.

Why Reform Is Needed

Kentucky's teacher pension plan is one of the worst-funded plans in the country. It has only about half the money it needs to pay for the benefits promised to current teachers and retirees. The state and its districts have more than doubled their contributions into the plan over the last ten years, and Kentucky employers are now contributing almost 30 percent of each teacher's salary into the plan. Most of that is going toward debt, not actual benefits for teachers, but even those increased contributions have not been enough to reduce liabilities or improve the plan's funding ratio.

Like a lot of other states, Kentucky's teacher pension plan is also back-loaded. For a new, 25-year-old teacher just starting out in Kentucky, she must commit to 26 or 27 years of continuous service before her pension benefit will be worth more than her own contributions.

Republican Governor Matt Bevin has been working for months to fix these problems, but he's made a lot of missteps along the way. He shut out teachers from the process, failed to be fully transparent in his plans, and has publicly chastised teachers and their union leaders. Moreover, earlier proposals would have altered the benefit promises made to existing retirees and current teachers. Those proposals, and communications messaging that sounded like attacks, have contributed to the current rancor in Kentucky.

But set aside the process for how we got here for the moment, and consider what's in the actual bill that passed the legislature last week. It makes no changes to current retiree benefits, and it includes only minor changes for current teachers, mainly around how sick leave is calculated in benefit formulas. The most significant change is it would place new teachers hired after January 1, 2019 into a different retirement plan called a cash balance plan.

What the New Plan Would Mean for Future Workers

Under the new plan, each teacher hired after 2019 will be required to contribute 9 percent of his or her salary, and employers will chip in another 8 percent. Kentucky teachers do not get Social Security, so these relatively high contribution rates are especially important.

The new cash balance plan is technically a defined benefit plan, but rather than defining the amount teachers receive through a back-loaded formula, each teacher will receive a guaranteed return on his or her contributions. In Kentucky, the state will credit each teacher with 85 percent of the plan's 10-year rolling average return. If the plan hits its investment return assumptions, that will translate into a return of 6.375 percent. In reality, it could go lower than that if the market returns are lower, but the 10-year rolling average should protect against any short-term fluctuations. Moreover, the state guarantees that no teacher will ever lose money, even if the markets tank and the actual returns are less than 0.

The new plan does not get rid of the existing unfunded liability, but the cash balance plan would ensure the state did not accrue any additional unfunded liabilities that would eat further into discretionary education budgets. The bill also includes other funding provisions to put the state's finances on a more responsible path going forward.

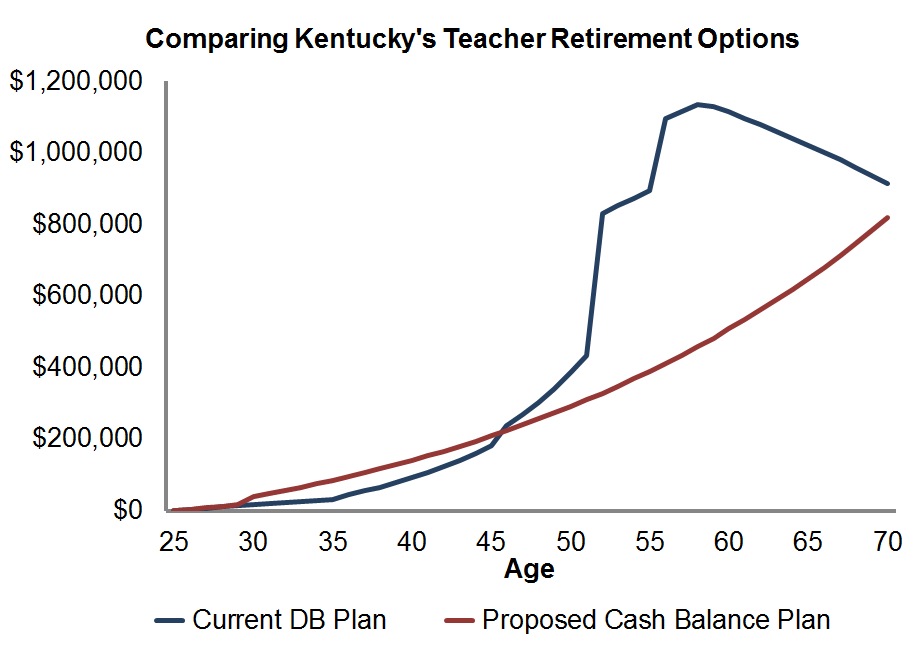

I created the graphic below to show how individual workers would accrue retirement assets under each plan. For comparison’s sake, I assumed the teacher was a female who begins her career at age 25 (see my full assumptions at the end of the post). Due to the five-year vesting requirement under both plans, benefits look nearly identical for the first four years, but the cash balance plan starts looking better once the teacher vests and qualifies for the employer contributions. At year 10, the cash balance plan account would be worth about $84,000, compared to just $32,000 under the old defined benefit pension plan.

Because the defined benefit plan bases its formula on final average salaries that are frozen in time, it delivers benefits in a more back-loaded fashion. For long-term veterans, the current plan would have been better. For a teacher who stays for more than 21 years of service, she would have earned more in the way of retirement wealth through the old plan. The figures are likely to look similar, albeit with shorter cross-over points, for educators who begin their service in Kentucky at later ages.

Still, the cash balance plan is at least competitive with the defined benefit model for large groups of Kentucky teachers. Although the graph pictured here doesn’t do it justice, the state's actuarial assumptions on turnover rates suggest that less than half of new teachers will reach 21 years of service.

The new cash balance plan will do a better job of providing all future Kentucky teachers workers with secure, portable retirement regardless of how long they stay, which is especially important given that Kentucky does not offer Social Security. The state has to balance the goal of providing a basic floor of benefits for all workers versus sufficient back-end benefits for full-career workers, and the cash balance plan does a better job balancing those priorities.

Table of Assumptions

Kentucky’s Current DB Plan

New Cash Balance Plan

Employee contributions

9.105%

9.105%

Employer contributions for benefits

7.615%

8%

Investment return assumption

7.5%

6.375%*

Inflation assumption

3%

3%

Vesting period

5 years

5 years

Formula multiplier

1.7% for years 1-9.9; 2% for years 10-19.9; 2.3% for years 20-26.99; 2.5% after 27 years

N/A

Normal retirement age

Any age w/ 27 years; Age 60 w/ 5 years

N/A

COLA

1.5%

N/A

Value after 10 years for someone who starts teaching at age 25 (2018 dollars)

$31,792

$84,457

Value after 35 years for someone who starts teaching at age 25 (2018 dollars)

$1,114,596

$507,817

*The cash balance plan awards interest of either 0% or 85% of the 10-year average return, whichever is higher. For this analysis, I’m assuming the plan will hit its 7.5% investment target and award employees interest credit of 85% of that (85% of 7.5% is 6.375%).

A recent Chicago Tonight article highlighted the top pension earners in the Illinois Teachers Retirement System. Only 18 of the top 100 are women, and the majority are white, male administrators. It’s not particularly surprising news, and confirms what we found in two new reports digging into discrepancies across race and gender in teacher wages and subsequent retirement benefits in Nevada and Illinois. In both reports, we found that while the majority of public school teachers (76 percent) are female, male educators out-earn women in terms of annual salaries and retirement benefits. This was a harsh reality on its own, but given that school districts typically operate with transparent, uniform salary schedules, the existence of gaps was that much more troubling.

While there are many potential contributing factors (a motherhood penalty, coaching stipends, lower salaries for female-dominated elementary teachers) it’s likely that disparities in promotions to higher-paying administrative positions play a role. The majority of teachers are female; however, the majority of superintendents (about 75 percent), are male.

Most states enroll all educators--teachers, principals, and superintendents--into one state pension plan. It's usually called the "teacher" plan. But the largest payouts from these "teacher" pension plans aren't actually going to teachers. Instead, the biggest benefactors are long-serving, highly paid administrators, who are predominantly male.

The predominantly female teacher workforce is paying into the same TRS system, but getting less out of it. And unlike a system like Social Security, which awards lower-paid workers with proportionately higher retirement benefits, teacher pension systems lack these kinds of protections. Illinois teachers also don’t pay into Social Security, which further penalizes teachers, but that’s another issue.

These disparities are one byproduct of a back-loaded system that creates a small group of winners at the expense of the majority of employees who lose out. In Illinois, 50 percent of new educators will not qualify for any pension at all (let alone a generous one). Pensions are often billed as especially beneficial to women -- and, if a teacher were to spend the entirety of her career working in the same system, she would earn a comfortable retirement. But we know that this isn't the case for the majority of teachers. All teachers, especially those who have been historically underpaid, deserve a fair, portable retirement plan.

As a part of its ongoing teacher diversity series, the Brown Center on Education Policy recently published a piece looking at different incentive structures districts use to attract people to the education profession. They found that some incentives are related with an increase in educator diversity. These findings are instructive and districts may want to consider them as a part of their teacher diversity efforts. That said, our research suggests that even once a person of color enters the education profession, she likely will still face significant barriers to advancement and higher salaries.

The Brown Center’s study relied on 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS), which provides information on the context of public and private schools across the country. Among the race-neutral financial incentive policies they studied, they found that offering relocation assistance, loan forgiveness, and bonuses for excellence in teaching are associated with increased staff diversity. As such, they recommend districts interested in increasing racial diversity explore these racially-neutral financial incentive structures.

These findings are important in their own right. Nevertheless, diversifying the education workforce does not stop after recruitment. More must be done to address the fact that educators of color must contend with additional barriers once they enter the profession.

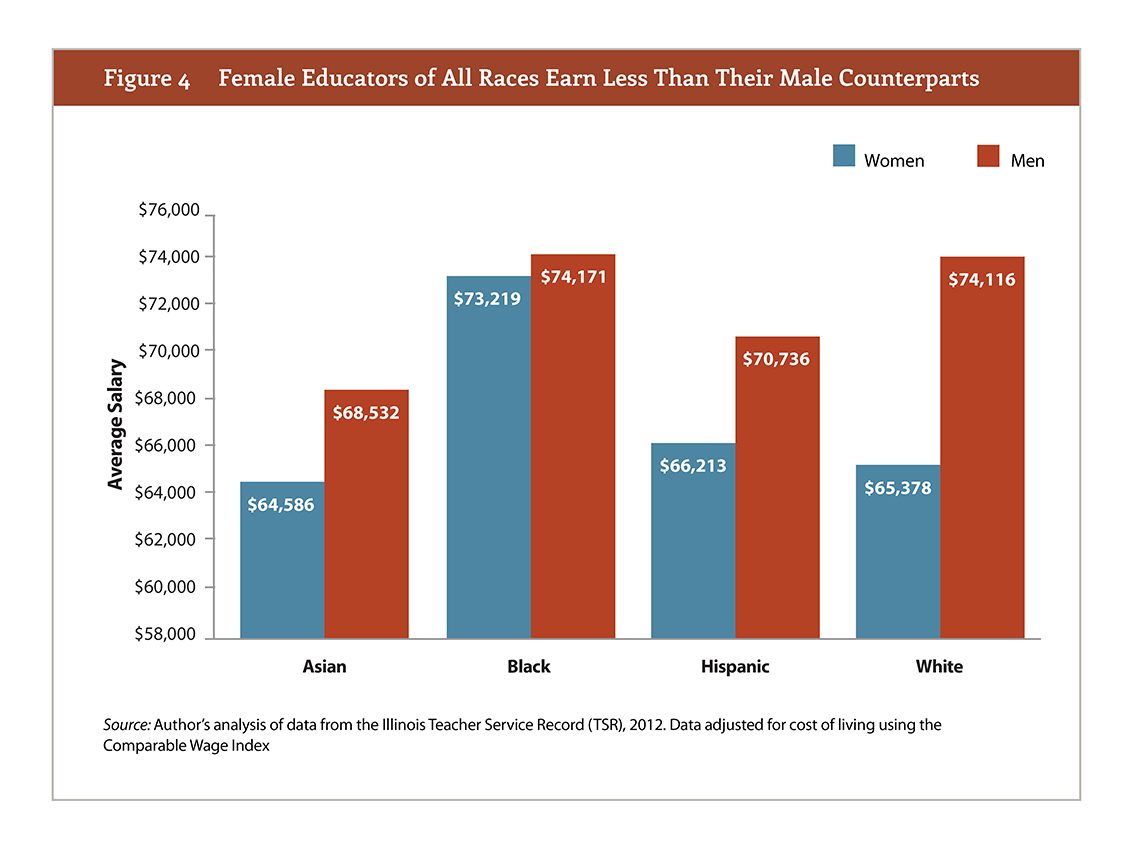

In our recent report we explored race-and gender-based salary gaps in Illinois. We found that women earn salaries that are on average $5,500 less than what men earn. As shown in the graph below, we also found significant gender-based pay gaps within races and ethnicities. Hispanic women, for example, earn on average $4,500 less in salaries than Hispanic men.

The story is less clear when it comes to across race salary gaps. At first glance, it appears that black educators are the highest paid, while Hispanic and white educators earn comparable compensation. But as my colleague Chad Aldeman and I demonstrated in a recent piece, digging deeper into the data reveals that black educators typically had to work longer and overcome significant barriers along the way to earning a higher salary.

We found that black educators are promoted and earn their master’s degrees much later in their career than white educators. This has a meaningful impact on their salaries since most district salary schedules assign the most significant pay bumps to additional degrees and administrative jobs. In Chicago Public Schools (CPS), black educators typically earn their master’s degree 3.5 years later than white educators, and those black educators who climb the leadership ranks do so five years later than their white colleagues. As a result, black educators need to work longer to earn the same aggregate compensation as white educators.

The silver lining for black educators is that they eventually acquire master’s degrees at higher rates than white educators and tend to work longer. Since teacher pensions are a function of salary and years of experience, this means that those who stick around earn a slightly greater reward in retirement. That may be cold comfort, however, since they had to suffer through many years of lower salaries and barriers to advancement. And, that doesn’t account for the many black educators who leave the profession without ever qualifying for a pension. Even those who remain may not ever make-up the gaps from earlier in their career.

We need to recruit educators of color, but we also need to retain them. Salary schedules, despite their uniformity, appear insufficient to guard against race-based disparities. Thus, as districts consider how to diversify their workforce, they must consider their recruitment pipeline AND their hiring and promotion practices to ensure that educators of color are treated fairly and enjoy equal opportunity. Otherwise, districts risk undermining their important diversity goals by asking educators of color to accept slower salary growth.

The recent firing of FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe prompted a political firestorm. In addition to the posturing and prognosticating, many observers were outraged that he was fired just hours before he could retire with full pension benefits. The concept of suddenly losing your retirement savings is understandably alarming to most Americans. If nothing else, the McCabe example is a good reminder that at-will employment and back-end “guaranteed” benefit systems are not always a sure thing. For that reason, the McCabe story draws many parallels to the problems with current teacher retirement benefits.

Let’s first discuss the real consequences of McCabe’s firing on his pension. Then, tackle how the worry over his financial future is more aptly applied to teachers and their pension benefits.

McCabe was fired right before his 50th birthday. The timing is significant because under the Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS), law enforcement officials qualify for early retirement with full-benefits at age 50 if they have at least 20 years of service. Other federal employees who do not work in law enforcement, say at the U.S. Department of Education, aren’t eligible for this deal.

So, McCabe’s pension hasn’t been emptied out. But that isn’t to say it hasn’t been negatively affected. McCabe won’t qualify for full benefits for another 7 years, his multiplier will get bumped down, and he lost post-employment health coverage. In the end, this adds up to a considerable financial loss. According to an analysis from the Urban Institute, McCabe lost over $1 million in total pension wealth, amounting to around three-quarters of its total value.

Some have argued that it’s not worth shedding tears over McCabe’s predicament (at least in terms of his retirement), since federal pensions are generous. I’m not particularly interested in litigating how much financial loss is worthy of sympathy. However, it is fair to say that in the end McCabe still will receive a pension. And in the meantime, he likely will be able to find gainful employment elsewhere, retire again, and collect Social Security.

In some ways, McCabe is more fortunate than most teachers.

Unlike federal employees like McCabe, who qualify for retirement benefits after five years, some states require teachers to stay much longer. 20 states require teachers to stay 7 or more years, and 15 states impose a 10-year waiting period. By our estimates, about half of new teachers never qualify for a pension at all.

Teachers face other barriers to a healthy retirement. Unlike the federal government, which employs workers all over the country (and even the world), state pensions are limited to state boundaries and are not portable. As a result, a teacher who moves to a new state has to participate in two pension systems. This can dramatically decrease her pension wealth in retirement.

Additionally, since the mid-1980s all new federal workers have been enrolled in Social Security. But Social Security participation is still optional for states, and around 1.2 million teachers are not able to participate. That makes them even more at risk from poorly structured state pension plans.

And finally, McCabe has more retirement plan options than the typical teacher. In addition to participating in Social Security, he is enrolled in the low-cost defined contribution (think 401k) federal retirement program, Thrift Savings Plan (TSP). All the while he also is in the federal pension system. Teachers typically do not have as many options for their retirement.

Although McCabe’s pension is in the news and receiving the public’s attention, it is teachers who regularly experience retirement insecurity. The problem is that state pension systems – as they are currently constructed – do not meet the retirement needs of today’s educator workforce. It is possible to avoid large peaks and valleys and structure benefits in ways that are more suited to recruiting and retaining high-quality workers of all ages.

At this point we don’t know much about whether McCabe deserved to be fired or not. We do know, however, that his pension paid a hefty price. Hopefully the public attention on this issue will broaden into a wider discussion about how best to ensure public employees’ retirement needs are met.