There are five things all Texas teachers should know about their retirement benefits:

- The Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) of Texas is back-loaded, and it leaves the majority of its teachers without adequate retirement benefits.

- The TRS plan is one of the stingiest in the country. On average, Texas teachers receive less money toward retirement than many of their peers in the private sector.

- TRS benefits are getting worse. Due to rising costs, state legislators have slowly reduced benefits provided to new teachers, and teachers who enter Texas schools today are getting a much worse deal than their predecessors.

- Texas lets each individual school district decide whether they want to enroll their teachers in Social Security, creating a patchwork of coverage that is not good for teachers or employers.

- Texas has better options for public servants. In Texas, municipal and county workers are covered by retirement plans which do a better job of providing adequate retirement benefits to all workers.

Each of these points deserves its own section, so I’ll break them down one by one.

1. The TRS system is back-loaded, and it leaves the majority of its teachers without adequate retirement benefits.

The Texas TRS plan is a fairly typical teacher pension plan. As a defined benefit plan, it offers workers a retirement benefit that’s equal to 2.3 percent multiplied by their years of service and their final average salary. As an example, if a teacher taught in Texas public schools for 15 years, and her salary averaged $60,000 over her last five years of teaching, she’d be eligible for annual benefits worth $20,700. The math looks like this:

Annual Pension = 2.3 percent * Years of Service * Final Average Salary

Annual Pension = 2.3 percent * 15 years * $60,000

Annual Pension = $20,700

In Texas, teachers must serve at least five years before qualifying for a pension (this is called the “vesting” period). The state also sets rules on when teachers can begin collecting their pension. For teachers hired today, they can begin collecting a pension check at age 65 if they had at least five years of service, or age 62 if they had more than 18 years of service. (Teachers may also begin collecting retirement benefits at younger ages, but those benefits are reduced for every year early they are claimed.)

This may sound fairly simple, but it’s complicated by the fact that the “Final Average Salary” number is calculated based on the years in which it was earned. That is, if our hypothetical teacher began her career at age 25 and served 15 years, her pension would be based on her salary at age 40. But, critically, she wouldn’t be able to collect her pension until age 65. By that time, inflation would have worn away the value of her pension significantly.

This rule has the effect of limiting how much early- and mid-career workers earn in retirement benefits, and it makes later-career earnings especially important. This system also has the effect of leaving many short- and medium-term workers with meager retirement benefits. In fact, these teachers would often be better off withdrawing their own contributions, with minimal interest, rather than waiting to collect a pension. (Individual teachers should consult with TRS or a financial advisor to find out what's best for them.)

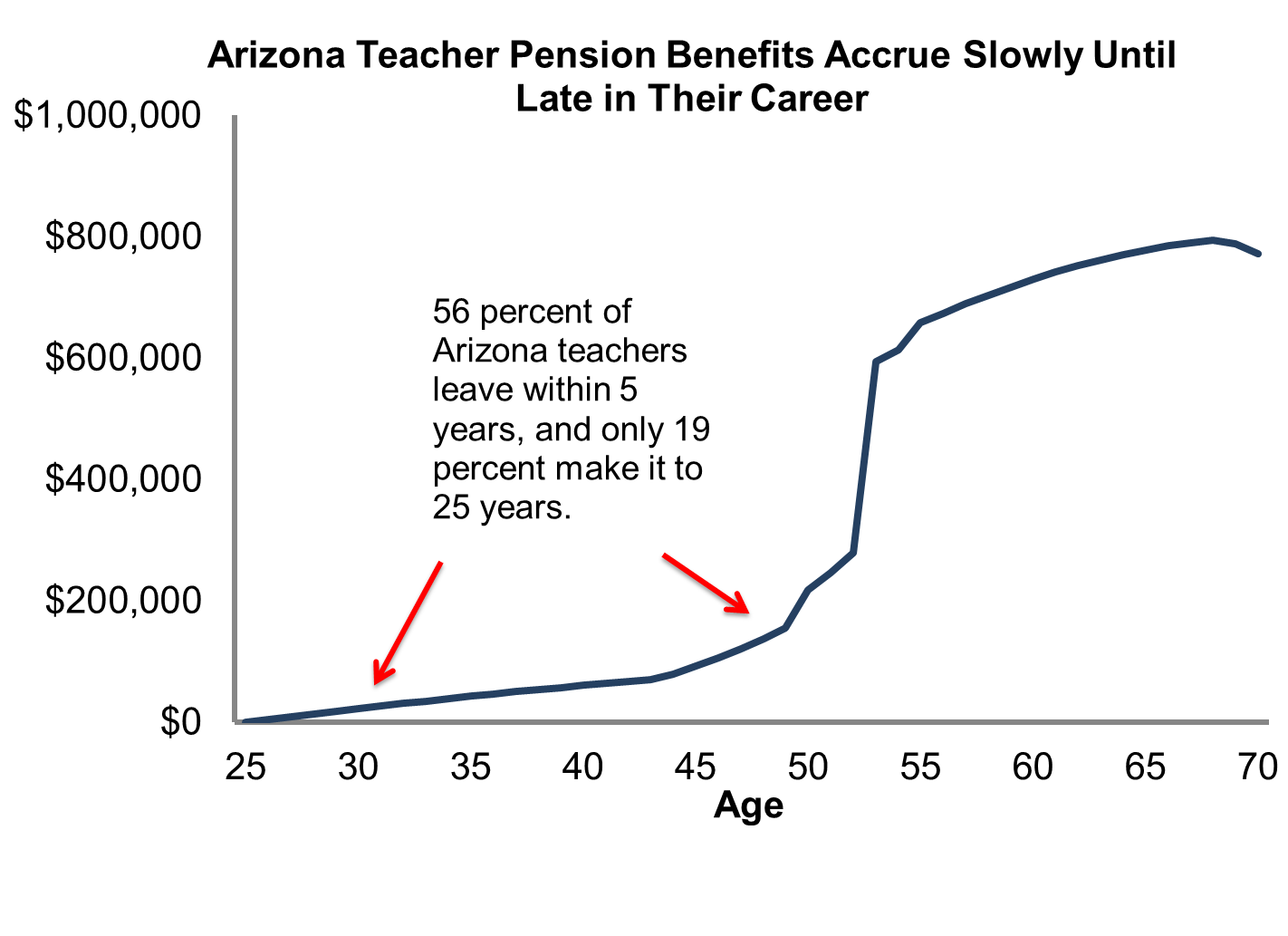

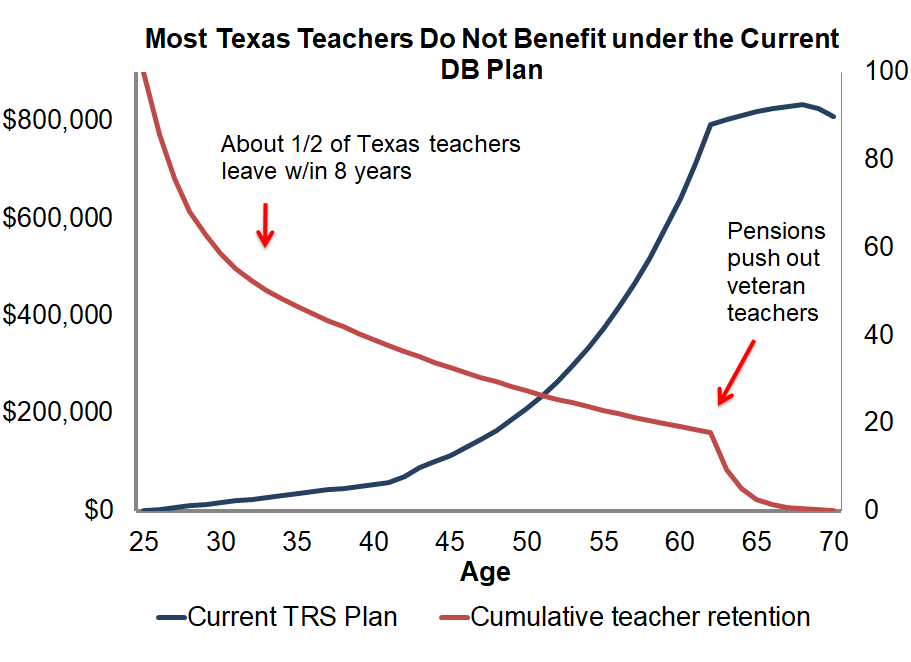

This situation creates a mismatch between Texas’ retirement benefits and the behaviors of its teachers. The graph below shows this visually. The blue line represents how retirement benefits accumulate under the TRS plan for someone who begins teaching in Texas at age 25. As the graph shows, benefits grow slowly for the first 20 or 25 years, and they only begin growing faster as teachers close in on the normal retirement age.

This is not an insignificant problem, because most teachers are gone well before those increases kick in. In the graph below, the red line shows the cumulative teacher retention rate in Texas, based on TRS’ own observations about employee behavior. The state estimates that about half of all new teachers will serve less than eight years, and two-thirds will serve less than 20 years. These teachers will need to find other ways to achieve a secure retirement beyond the TRS system.

In sum, the TRS plan offers adequate benefits only to long-serving veteran teachers. As I’ll show in the last section, there are other models within Texas that could do a better job of protecting all teachers. But first, it’s important to understand the other ways the current TRS system is failing Texas teachers.

2. The TRS plan is one of the stingiest in the country.

Most people hear the word “pension” and assume it must be good for workers. But that’s not always true, and Texas legislators have created a pension plan that is actually quite stingy, from an employer’s perspective. Texas teachers are required to personally contribute 7.7 percent of their salary, but their employers are only contributing about 2.4 percent of salary toward teacher retirement benefits (in actuarial terms, this is called the plan's "normal cost"). That’s less than a typical 401k in the private sector, where employers routinely chip in a 3, 4, or 5 percent match, and it's less than teacher retirement plans in other states.

There are two reasons the numbers above may not match with the public’s perception of the TRS pension plan. One is that the 2.4 percent normal cost represents an average across the entire plan. Some long-serving Texas educators will eventually qualify for pensions that are worth far more than that, while most workers will receive far less. The TRS system includes a number of cross-subsidies, and it works especially well for workers, like principals and district superintendents, who earn higher salaries and have more longevity than classroom teachers, aides, or other school support staff.

The second reason the TRS plan might seem more generous than it is is because Texas employers are contributing another 5.34 percent of teacher salaries to pay off unfunded liabilities (which actuaries refer to as the "amortization cost"). In total, Texas school districts are paying the same amount as employees, but much of the employer cost is going to pay down debt, not for actual employee benefits. This is not an insignificant sum, and it creates a disconnect between the amount employers are paying and the benefits that individual teachers and retirees receive. Worse, these unfunded liabilities have forced the state to cut benefits over time, such that new teachers starting out today are getting an even worse deal than their predecessors.

3. TRS benefits are getting worse.

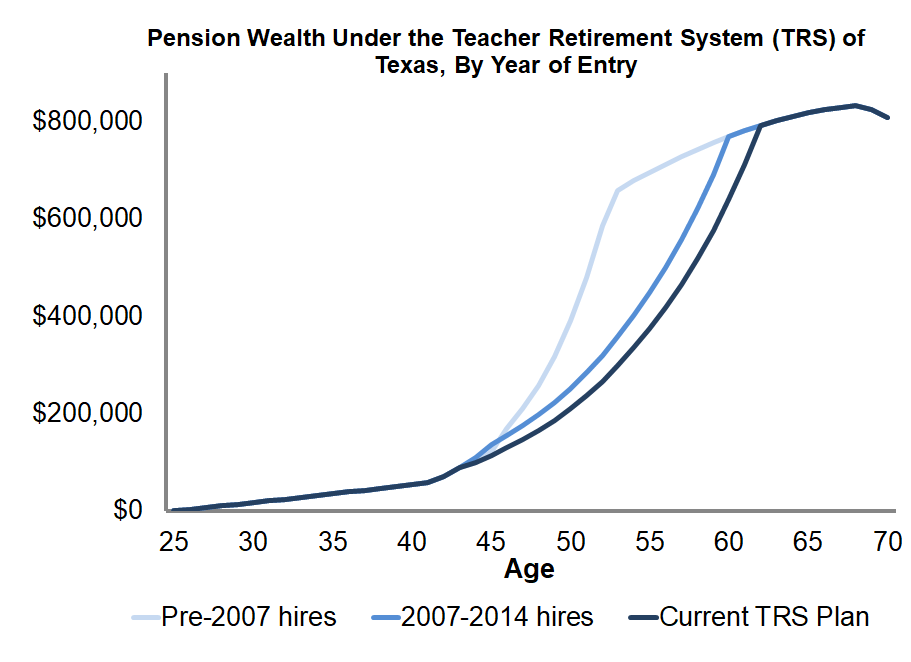

Like a number of other states, Texas has been forced to reduce benefits offered to new entrants in recent years. Texas has chosen to do this primarily by changing the normal retirement age, the point at which teachers are first eligible to start collecting unreduced retirement benefits. All workers are eligible to retire at age 65 with five years of service, but workers hired prior to 2007 could also retire at any age once the sum of their age and years of service passed 80 (commonly referred to as “the rule of 80”). Teachers hired between 2007 and 2014 had slightly less generous rules in that that the rule of 80 only applied to those age 60 or older. Texas again made changes for teachers hired after 2014. Now, teachers must wait until age 62 before qualifying for rule of 80 benefits.

These changes have eroded TRS benefits and made them even more back-loaded. Like the first graph above, the graph below shows how retirement benefits accumulate for a teacher who enters her Texas service at age 25, but this time it shows how benefits accumulate based on the year she began working in Texas schools. As the graph shows, the shifts in the normal retirement age have dramatically changed how teacher retirement benefits accumulate. The darkest blue line represents the current TRS plan, compared to the lighter-colored lines, which represent the benefits offered to teachers hired in earlier years. As the graph shows, teachers hired prior to 2007 had much more generous benefits than those hired more recently.

These changes have effectively made the TRS plan even more back-loaded, meaning fewer and fewer teachers have access to adequate retirement benefits. That’s not a good situation, and it puts more and more teachers at risk of an insecure retirement. This is particularly problematic due to the fact that most Texas teachers lack Social Security benefits.

4. Texas lets each individual school district decide whether they want to enroll their teachers in Social Security.

Due to a historical quirk, Texas lets each school district decide whether they want to offer Social Security to their employees. 17 districts, including Austin and San Antonio, cover all their workers, and another 31 offer some employees coverage. Some regional service centers do as well, as do many Texas universities and community colleges. But that leaves some 1,200 Texas school districts that do not provide Social Security benefits to their workers.

This messy hodgepodge is not good for workers or employers. From a worker’s perspective, they lose out on the nationally portable, progressive benefit structure that Social Security provides. That sort of protection is especially important given the back-loaded nature of the state-run TRS plan. Teachers may also not know at the time of being hired that their employer doesn’t offer Social Security benefits. They may take Social Security coverage for granted, and only find out later that they weren’t paying in and thus won’t receive benefits for those lost years.

Employers bear the Social Security burden in other ways. Social Security coverage might be good for workers, but many people under-estimate its true value. An employer like San Antonio that enrolls teachers in Social Security might be doing right by its workers, but it might also be at a competitive disadvantage in attracting and retaining talent if workers don’t fully appreciate Social Security’s value.

Ideally all teachers would have access to Social Security benefits, but Texas’ split Social Security coverage, and its back-loaded TRS plan, leaves Texas workers in a particularly precarious situation.

5. Texas should look within the state for better retirement options for teachers.

Luckily, Texas already has two alternative models in place that balance the retirement security of workers with financial stability for employers. These plans already serve hundreds of thousands of public-sector workers in Texas, and they could be adapted for school districts and teachers. Both plans are legally considered to be defined benefit plans, but rather than using formulas based on years of service, they guarantee workers a certain rate of return.

Those two plans, the Texas Municipal Retirement System (TMRS) and the Texas County & District Retirement System (TCDRS), are technically called defined benefit cash balance plans. They collectively serve about 350,000 city and county employees, including nurses, mechanics, road crew workers, sheriffs, attorneys, office workers, jailers and judges. Both plans are operated statewide, and they allow participating cities to select an employee contribution rate, an employer match, and a vesting period.

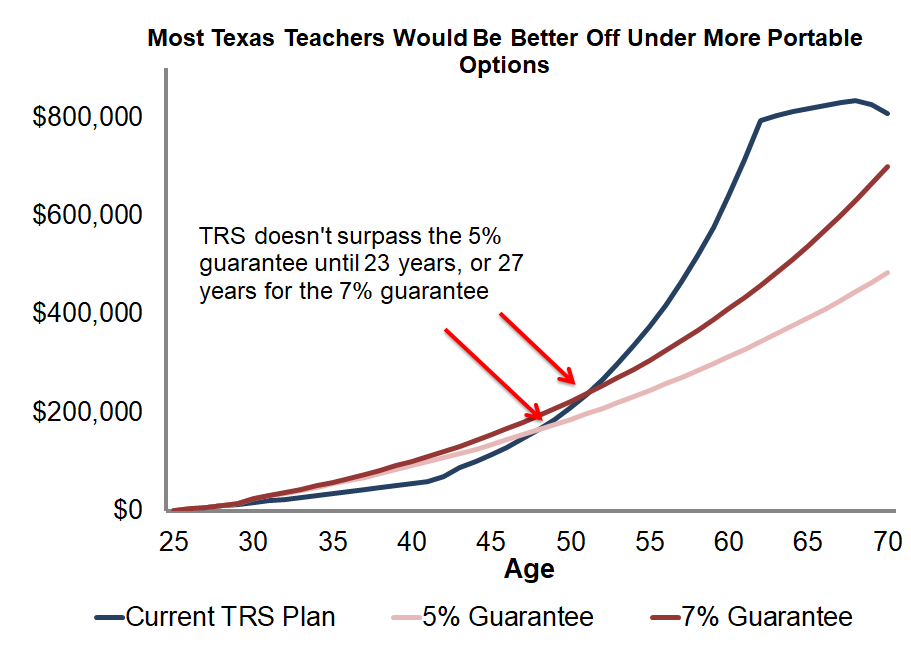

In these types of guaranteed plans, the contributions go into an account in the worker's name. The plan invests the money and guarantees a rate of return, at least 5 percent under TMRS and 7 percent under TCDRS. This provides a more portable benefit with a steadier accumulation of assets than the TRS pension plan. Like TRS, both of these plans help employees when they’re ready to retire. When employees become eligible to retire, the money in their account is annuitized into regular monthly paychecks just like a pension. These paychecks allow for sustained monthly income, mirroring the benefits and stability of a traditional pension plan without the back-loaded accumulation under the current TRS pension plan.

The graph below compares the TRS plan offered to new hires (the same dark blue as in the earlier graphs) against cost-neutral guaranteed plans like the ones currently operated by TMRS (a 5 percent guarantee, represented in pink) and TCDRS (a 7 percent guarantee, represented by the red line). For comparison’s sake, each plan is based on the assumption of a female teacher who begins her career at age 25. Due to the five-year vesting requirement assumed under all three plans, they look nearly identical for the first four years, but the guaranteed plans start looking better once the teacher vests and qualifies for the employer contributions. Because the TRS pension plan bases its formula on final average salaries that are frozen in time, it delivers benefits in a more back-loaded fashion. From a worker’s perspective, they would need to work 23 consecutive years before the TRS plan would be better than a simple 5 percent guarantee, or 27 consecutive years before the TRS benefits would exceed the 7 percent guarantee option. Although these “crossover” points would be shorter for teachers who begin their service at older ages, the majority of teachers would still be better off in the guaranteed rate plans due to high early-career turnover rates.

The plans modeled here assume contributions are identical to the current TRS plan. Enrolling future teachers into one of these plans would not make the current TRS unfunded liability go away, but the guaranteed plans would help the state cap its debt costs at its current levels.

In summary, Texas teachers currently lack secure, portable retirement benefits. Without action, the next generation of teachers are likely to have an even more precarious retirement situation. Luckily, Texas policymakers have good models to build on that already exist within the state. Adapting one of those models to the teacher workforce could help improve the state’s finances and ensure that all teachers are building sufficient retirement assets, no matter how long they work in Texas public schools.

A recent article from the Connecticut Post looked at the budget priorities for outgoing Governor Dannel Malloy, including teacher pensions. Connecticut's teacher pension system is in particularly bad shape, and the article notes that, "according to one study, [Connecticut's] annual contribution could more than quintuple, topping $6.2 billion by 2032."

While almost every state has funding problems, Connecticut is unique in that the state takes the responsbility for paying the full cost of teacher pensions. That is, unlike other states, where the costs of teacher retirement plans are born by the school districts that employ the teachers, Connecticut pays for teacher pensions out of its state budget. And that has consequences:

The current system of funding teacher pensions also is regressive.

To make his point, Malloy contrasted one of the state’s most affluent communities, Greenwich, with one of its poorest, New Britain. Both have similar populations and school enrollment totals, but Connecticut spent $24 million more last year to cover pension costs for retired Greenwich teachers than for those from New Britain.

In simple terms, Greenwich can afford to pay much higher salaries than New Britain can, yet it gets more help from the state on a per capita basis to provide pensions for its retired teachers.

There are a handful of states, like Illinois, Kentucky, and New Jersey, that also pay for teacher pension costs out of the state's general fund. These states tend to be in worse financial shape, since state legislators face annual decisions over whether they should contribute to the pension fund or use the money elsewhere. And inevitably, politicians find other places to spend money, and they regularly short the pension fund. That has implications for the financial health of the plan, but Connecticut is a good reminder that paying for pension plans this way also leads to large and inequitable subsidies. The biggest winners from this arrangement are communities with a stable teaching workforce, like Greenwich, that can afford to pay high salaries. A "blue" state like Connecticut is operating a pension system that is neither fair nor progressive.

Connecticut provides a stark example of funding inequities buried in statewide pension plans, but every state has benefit inequities even when districts are responsible for paying the tab. That's because most states are operating statewide teacher pension plans, and they set contribution rates as a function of all teachers in the state. In that arrangement, school districts with high teacher turnover and low salaries will be forced to subsidize the pensions earned in districts with higher teacher stability and higher salaries.

The politics of this are especially confusing, because the loudest defenders of pension plans are Democrats who support efforts to increase equity in other areas of policy. But on pensions, Democrats are often the ones fighting to preserve systems that deepen financial inequities.

Taxonomy:Over the summer, the Supreme Court ruled in the Janus v AFSCME case that public-sector unions can no longer collect "agency fees," the mandatory fees that unions charged employees to cover the costs of collective bargaining. The court ruled that agency fees were an unconsitutional form of forced speech, since collective bargaining in itself is a political act. (For more on the details of the case, see this comprehensive explainer deck from my Bellwether colleagues.)

The conventional wisdom on the effects of Janus seems to go like this:

1: With the loss of agency fees, teachers unions will have fewer paying members and thus smaller budgets.

2: With smaller budgets, teachers unions will be less effective at lobbying for change on behalf of their members, and teachers will have lower salaries and worse working conditions.

3: Lower pay will harm the teacher workforce, through worse recruitment and higher turnover rates.

But what if these issues are not as directly related as theory might predict? My thinking on this question was challenged by an academic paper that came out a few months before the Janus case was decided. In that paper, political scientist Agustina Paglayan looked at the timing of when states adopted collective bargaining and how that related to changes in teacher salaries and overall education spending (see an Education Week write-up here, or read the full study here). Paglayan found that states with high education spending and high teacher salaries were more likely to become unionized. In fact, the notion that teachers unions caused teacher salaries to rise appeared to be backwards: Places that were already investing in public education and paying their teachers well were also likely to allow those teachers to unionize. Paglayan's paper included state-by-state graphs showing that unionization often followed large increases in school spending and teacher salaries, not the other way around.

If we apply the lessons from Paglayan's research, the Janus case may well weaken unions, but we should decouple that effect from predictions about changes in education spending or teacher salaries. The connection between teachers unions and the teacher workforce may not be as tight as the conventional wisdom might predict.

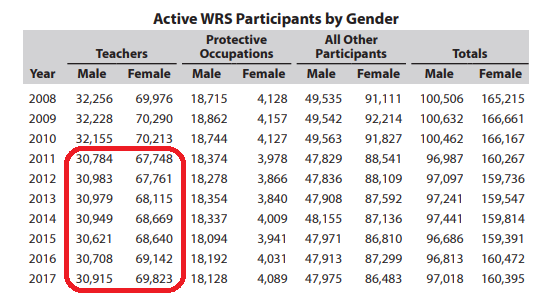

The recent history in Wisconsin presents a useful modern comparison. In 2011, Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker signed a controversial piece of legislation known as Act 10. The bill restricted collective bargaining to base wages, required annual recertification for bargaining unit representation, and raised teacher contribution rates to the state pension and health care systems. Many observors predicted these changes would devastate the teacher workforce in Wisconsin.

We already have some preliminary results, and Wisconsin teacher union membership and union revenues did indeed go down. There's also been some preliminary research suggesting that more Wisconsin school districts are experimenting with differential pay, which may create a more uneven spread between winners and losers.

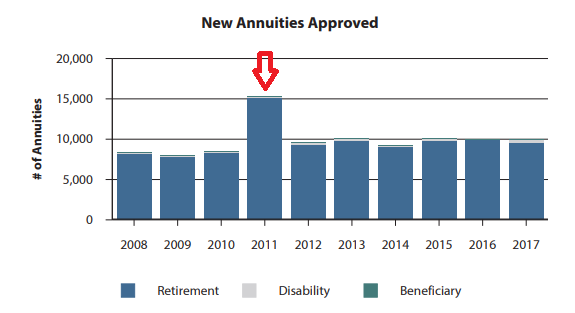

But the more drastic predictions about the demise of the Wisconsin teacher workforce have not transpired. Today, there are more educators working in Wisconsin schools (over a time when student enrollment actually dipped slightly), and average salaries have kept up with other states (although not inflation, see more below). After an initial surge of retirements when the law passed in 2011, things have returned to normal. Meanwhile, turnover rates, salary growth rates, median years of experience, age, and retirement rates all look pretty much in line with long-term trends. And regardless of who wins the governorship tomorrow, school spending is likely to rise in the immediate future: Both Walker and his Democratic opponent, state schools superintendent Tony Evers, have proposed significantly more education spending.

To see how things are changing over time, I looked at the latest version of the Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) of the Wisconsin Department of Employee Trust Funds (ETF). This report compiles results and assumptions about different types of public servants, including teachers, who receive benefits through the Wisconsin Retirement System (WRS). The report breaks out the results by broad categories. It lumps all educators including school support personnel into one "Teacher" category, but classroom teachers represent the bulk of the category, and the data are broadly illustrative about the people working in Wisconsin school districts. Here's what the data show:

Leading up to 2011, Wisconsin was shedding public-sector jobs, especially in education. After Act 10 passed in 2011, Wisconsin was slow to rebuild its teacher workforce, but it has happened over time. Today, Wisconsin is back to about where it was in 2010. Meanwhile, K-12 student enrollment has fallen by about 0.5 percent over this same time period.

As we've written before, Act 10 did seem to lead to a large exodus of workers right when it passed. This surge may have led people to believe this was a new normal, but in subsequent years the number of workers retiring each year has returned back in line with its prior baseline. Contrary to what we might expect, this mass exodus of veteran teachers did not seem to harm student achievement. This is consistent with evidence from the retirement world, where early retirement programs that induce many veteran teachers to retire have not led to declines in student performance.

In fact, the teacher workforce in Wisconsin today looks pretty similar to what it looked like in the past. Since Act 10 passed in 2011, the average age of Wisconsin teachers has dropped from 43.5 to 43.3 years old. It hasn't budged at all since 2013.

Similarly, the average years of experience has also not changed much, and it's risen from 12.4 in 2011 to 12.6 years of experience today.

Average salaries show a similar trend. The graph below is in nominal dollars, so it presents a slightly rosier picture than what Wisconsin teachers might be feeling. In inflation-adjusted terms, Wisconsin teacher salaries are lower today than they were in previous decades. But you could have said the same thing at the end of 2010, before Act 10 passed. In real terms, average teacher salaries in Wisconsin were much higher in the late 1980s. Act 10 had nothing to do with this long-term decline.

The slide in average teacher salaries is also not unique to Wisconsin. In real terms, teacher salaries have been flat or declining all across the country, and the changes in Wisconsin in recent years put it in the middle of the pack on this metric.

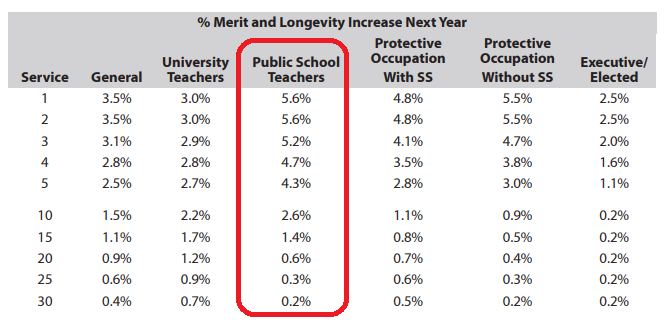

All of the measures we've looked at so far show how things have changed over time, but it's also worth looking at how teachers compare to other types of public-sector workers in Wisconsin. According to the official WRS projections, teachers have faster salary growth rates than other types of public workers. (These growth rates are on top of inflation.)

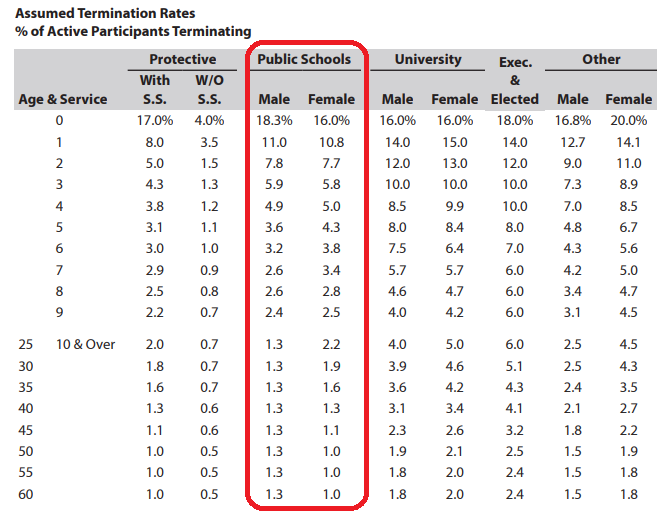

Again contrary to popular perception, public school employees in Wisconsin have comparable turnover rates as other public-sector workers, with the exception of a small group of protective service employees who do not receive Social Security. (In this context, "termination" means employees leaving the pension system. That is, teachers who transfer schools or districts are not counted in this statistic.)

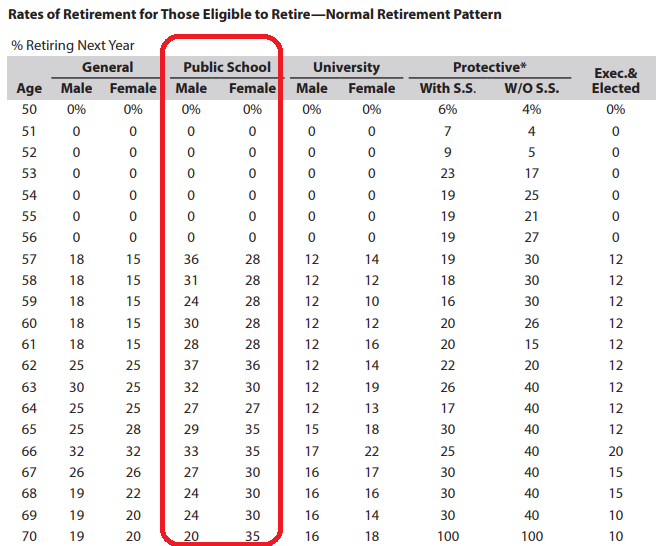

Wisconsin teachers also retire at younger ages than their public-sector peers (and much earlier than the typical worker in the private sector). According to this chart, the WRS assumes that 36 percent of male public school employees will retire when eligible at age 57, compared to 18 percent of similar general state employees. On a cumulative basis, that means very few Wisconsin teachers remain in the classoom into their 60s, and they have different retirement patterns than general state employees or university employees, despite them all being enrolled in the same retirement plan.

Overall, Act 10 had a large effect on Wisconsin teachers unions but hardly any effect on Wisconsin teachers. That distinction is important, and as we look to interpret the effects of the Janus decision, the Wisconsin example should remind us to be careful to separate out the effects on unions from the effects on teachers.

Taxonomy:Here in the United States, the vast majority of public school teachers are enrolled in traditional defined benefit pension systems. But that fact hides several points of nuance. Here are five key points to remember about teacher pensions:

1. Most public school teachers are enrolled in a traditional defined benefit (DB) pension plan

Unlike teachers in private schools, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that 89 percent of “primary, secondary, and special education school teachers” employed by state or local governments participate in a defined benefit (DB) pension plan. That figure is down slightly from 2009, when 94 percent of public school teachers participated in DB plans.

Those numbers are changing over time as more states transition to alternative retirement plans such as defined contribution or cash balance plans. Some states give new teachers a choice over which type of retirement plan they prefer, but the new plans usually only apply to new workers, so participation rates will fall slowly as more states transition away from the old DB pension model.

2. Enrollment in a pension plan does not necessarily guarantee teachers receive a pension

States impose rules called vesting requirements that determine how long a teacher must stay before she qualifies for a pension. The majority of states require teachers to serve for five years before qualyfing for a pension, and 16 states require teachers to serve for 10 years. Due to relatively high early-career turnover, large numbers of teachers won't reach these vesting requirements. In the median state, about half of all new teachers won't stay long enough to qualify for any pension at all. (See the numbers for your state here.) Whether they decide to switch jobs, move to another state, or leave the workforce entirely, many teachers are technically enrolled in a pension plan, but they may never actually receive a pension.

3. Even after qualifying for a pension, some teachers will cash out

Merely qualifying for a pension does not say much about how large that pension will be, and many teachers decide they'd rather withdraw their contributions than wait to draw a pension when they reach retirement age. For example, a 40-year-old teacher with 10 years of experience would likely qualify for a pension, but she may not be able to collect those payments until she turns 60 or 65. Her pension at that point will be based on the salary she earned while she was 40, and inflation will have worn away its value significantly. (For a longer explanation of how this works, see here.) This issue isn't as true for older teachers who are closer to retirement, but they may still decide they'd prefer a lump-sum withdrawal payment over monthly pension checks in retirement.

These are complicated decisions, and teachers should consult a financial professional to help determine what's best in their unique circumstances.

4. Unlike private-sector workers, not all teachers are covered by Social Security

About 40 percent of public school teachers, or about 1.2 million teachers nationwide, are not covered by Social Security. Those teachers are concentrated in 15 states— Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nevada, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Texas—and the District of Columbia, where many or all public school teachers neither pay into nor receive benefits from Social Security. Teachers in those states face substantial uncertainty and must rely more heavily on their employer retirement plans (state pensions) and personal savings.

5. The "average" teacher pension can be quite modest, but that can be a misleading statistic

While there's a debate about whether teacher pension plans are too generous, that debate is skewed by who ends up receiving benefits. For example, going back to our earlier example, for a teacher who quits working at age 40 with 10 years of service, her pension is likely to be quite modest by the time she's eligible to collect her benefit. In contrast, some long-serving, highly-paid employees wind up with pensions that surpass $100,000 a year or more. There are many more people like the former than the latter, but calculating the statistical average combines them all into one number.

Teacher pension plans today are very expensive, but the bulk of those costs are going to pay down unfunded liabilities, not for actual benefits for teachers. Once we take out the debt costs that states and districts are paying, the total retirement savings provided to teachers start to look worse. Moreover, pension plans distribute benefits in an uneven fashion. Some lifelong veteran teachers and school district administrators qualify for pensions that are quite generous, while the bulk of teachers will receive far less.

Teachers may take comfort with the fact they're enrolled in a pension plan, but they should check the fine print and consult a financial advisor to determine how long they need to stay in their respective pension plan in order to secure a solid foundation of retirement benefits.

There’s a common misconception that teachers’ retirement plans are gold-plated, extremely generous options. And for a very small pool, they do provide a secure retirement. But that’s not the case for the majority of teachers. To illustrate this, we dug into a sampling of states to see how they measure up, and ran the numbers to see if an alternative plan design might serve more of their workforce. Here’s what we found for Georgia.

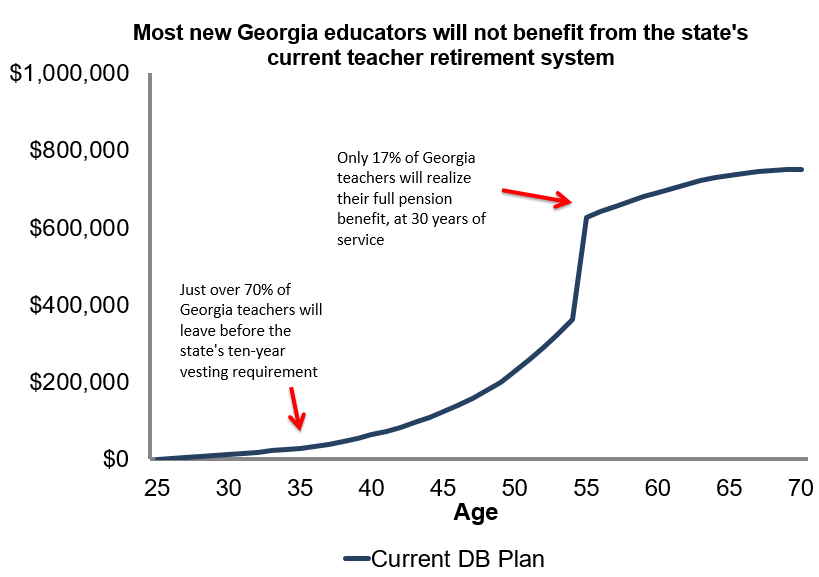

- Georgia’s current defined benefit plan is more extreme than most. The formula used by the Teachers Retirement System of Georgia (TRSGA) offers minimal benefits to short- and medium-term workers and requires an especially lengthy vesting period – ten years. If Georgia teachers stay nine years or less, they do not qualify for any pension or employer-provided retirement benefit at all.

In addition, not all Georgia teachers are covered by Social Security. It’s up to each district to decide whether to extend coverage to educators, and teachers in metro Atlanta, DeKalb, Fulton, and Clayton counties, who do not have Social Security coverage, are particularly vulnerable to a poorly designed state retirement system.

- Most Georgia teachers won’t actually benefit from their retirement benefits. In Georgia, 83 percent of teachers who begin their careers at age 25 will leave before reaching 30 years of service, which is the point when they’ll finally qualify for a benefit that’s more than their own contributions plus interest. The graph below compares pension wealth accrual to Georgia teacher retention rates, and captures this discrepancy.

- Given its current workforce demographics, most Georgia teachers would do better under a more portable retirement plan. A portable plan would better support Georgia’s mobile teacher workforce and allow educators to take their savings with them across state lines or out of the classroom. In addition, nearly all portable plan options would accrue benefits in a smoother fashion, rather than the state’s current back-loaded model. We know most Georgia teachers will leave before they reach peak pension wealth – they shouldn’t suffer from inadequate retirement savings because of it.

All Georgia teachers should have access to a portable, fair retirement plan, as well as Social Security coverage. The current system works for some, but not most of Georgia’s educators. A portable solution could better serve the state’s existing workforce.

- Georgia’s current defined benefit plan is more extreme than most. The formula used by the Teachers Retirement System of Georgia (TRSGA) offers minimal benefits to short- and medium-term workers and requires an especially lengthy vesting period – ten years. If Georgia teachers stay nine years or less, they do not qualify for any pension or employer-provided retirement benefit at all.

Teacher pension funds are complicated and can be difficult to understand. They’re not as straightforward as other retirement savings accounts, such as 401ks, nor are they like traditional investments in stocks. In a 401k, for example, the value of the retirement fund is determined by employer and employee contributions, plus the growth of those investments over time.

Defined benefit pension plans, like the ones serving 90 percent of public school teachers, don't work that way.

To be sure, teacher pension plans are invested in the market. However, individual teacher contributions and those made on their behalf by the state or school district do not determine the value of the pension. Instead, a teacher's pension wealth is determined by a formula based on her years of experience and final salary.

To further complicate matters, there often are several tiers within a state’s pension fund that provide different levels of benefits based on when a teacher was first hired. And of course, teacher pension funds can vary significantly from state to state.

How Teacher Pensions Work in Arizona

In Arizona, teachers are a part of the Arizona State Retirement System, which includes not only teachers but all state employees. Indeed, the system was established in 1953 and teachers voted to join two years later.

The basic structure of Arizona’s teacher pension is similar to that of other states. The figure below illustrates how a teacher pension is calculated in Arizona. It is important to note, however, that the state assesses an educator’s final salary based on their average salary from the past 5 consecutive years.

Generally, states use a consistent multiplier, for example 2 percent, for all teachers. However, Arizona is unique and applies four different multipliers depending on the teacher's years of service. This approach provides slightly more generous benefits to those teachers who serve the longest. As shown in the table below, for the first 19 years a teacher’s pension benefit will be calculated with a multiplier of 2.1 percent. Once they begin their 20th year teaching, however, the multiplier increases to 2.15 percent.

Table 1: Arizona’s Pension Multiplier

Years of Service

Multiplier

Less than 20

2.1%

20 to 24.99

2.15%

25 to 29.99

2.2%

More than 30

2.3%

There are a few other features of Arizona’s teacher pension plan that make it unique. First, unlike most states, Arizona does not have a vesting period. This means that educators qualify for a pension regardless of how long they serve. That pension may not be worth all that much, and educators can’t begin to collect it until they hit the state’s retirement ages, but immediate vesting does at least ensure all educators begin to accrue pension benefits immediately.

The state sets specific windows when teachers can retire with full benefits based on age and years of experience. For new teachers just startting out in Arizona, they can retire with their full benefits when they meet the following conditions:

- Age 65;

- Age 62 with at least 10 years of experience

- Age 60 with at least 25 years of experience; and,

- Age 55 with at least 30 years of experience.

Additionally, Arizona allows early retirement at age 50 with at least 5 years of experience, but teachers taking that option have their benefits reduced based on their years of experience and how early they are retiring.

As they work, teachers and their employers must contribute into the plan. Those contribution rates are set by the state legislature and can change year-to-year. In 2017, both the state and the employee contributed 11.34 percent of their salary to the pension fund. This year the rates are the same, but that may not always be the case.

Finally, in Arizona, as with most states, teacher pensions are not portable. This means that if a teacher leaves the state she can’t take her benefits with her, even if she continues working in the teaching profession. As a result, a teacher who moves states might have two pensions, but the sum of those two pensions is likely to be worth less than if she remained in one system for her entire career. In other words, the lack of benefit portability will hurt the long-term retirement savings of any educator who leaves teaching altogether or who crosses state lines to work in another state.

Arizona’s Teacher Pension System Heavily Favors Teachers with More Than 25 Years of Experience

An unfortunate feature of teacher pension systems is that they are severely back-loaded. In other words, benefits accrue extremely slowly and thus educators only earn valuable pensions after decades of service. This structure may work well for teachers who spend their entire career in classrooms in a single state, but it does not work as well for those educators who change jobs or are more mobile.

The graph below illustrates the benefit accrual rate for a typical Arizona teacher who begins teaching at age 25. The first thing to notice is that benefits accrue very slowly until they teach for about 25 years. However, According to the state’s own projections, only about 19 percent of teachers will remain in the profession long enough to reach their 25th year of service. In other words, for most teachers Arizona’s immediate vesting does not translate into a valuable pension benefit.

Figure 2: How Retirement Assets Accumulate in the Arizona State Retirement System

There is a severe mismatch between Arizona’s teacher pension system and the educator workforce in the state. Pensions are great at providing valuable retirement benefits to those who spend their entire career in schools in one state. But the Arizona teacher workforce doesn’t fit that model. As a result, the vast majority of teachers in Arizona will leave their years of service with only meager retirement benefits.

Overall, Arizona’s teacher pension system is a bit more complicated than the typical state plan. But as with most state pension funds, Arizona’s teachers must remain in the profession for nearly three decades to earn a quality retirement benefit. With that in mind, new and current teachers in Arizona should think carefully about their career plans and how they interact with the state's retirement plan. Educators who leave the profession early, even if they qualify for a small pension, will unintentionally do damage do their long-term retirement savings.