As a part of its ongoing teacher diversity series, the Brown Center on Education Policy recently published a piece looking at different incentive structures districts use to attract people to the education profession. They found that some incentives are related with an increase in educator diversity. These findings are instructive and districts may want to consider them as a part of their teacher diversity efforts. That said, our research suggests that even once a person of color enters the education profession, she likely will still face significant barriers to advancement and higher salaries.

The Brown Center’s study relied on 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS), which provides information on the context of public and private schools across the country. Among the race-neutral financial incentive policies they studied, they found that offering relocation assistance, loan forgiveness, and bonuses for excellence in teaching are associated with increased staff diversity. As such, they recommend districts interested in increasing racial diversity explore these racially-neutral financial incentive structures.

These findings are important in their own right. Nevertheless, diversifying the education workforce does not stop after recruitment. More must be done to address the fact that educators of color must contend with additional barriers once they enter the profession.

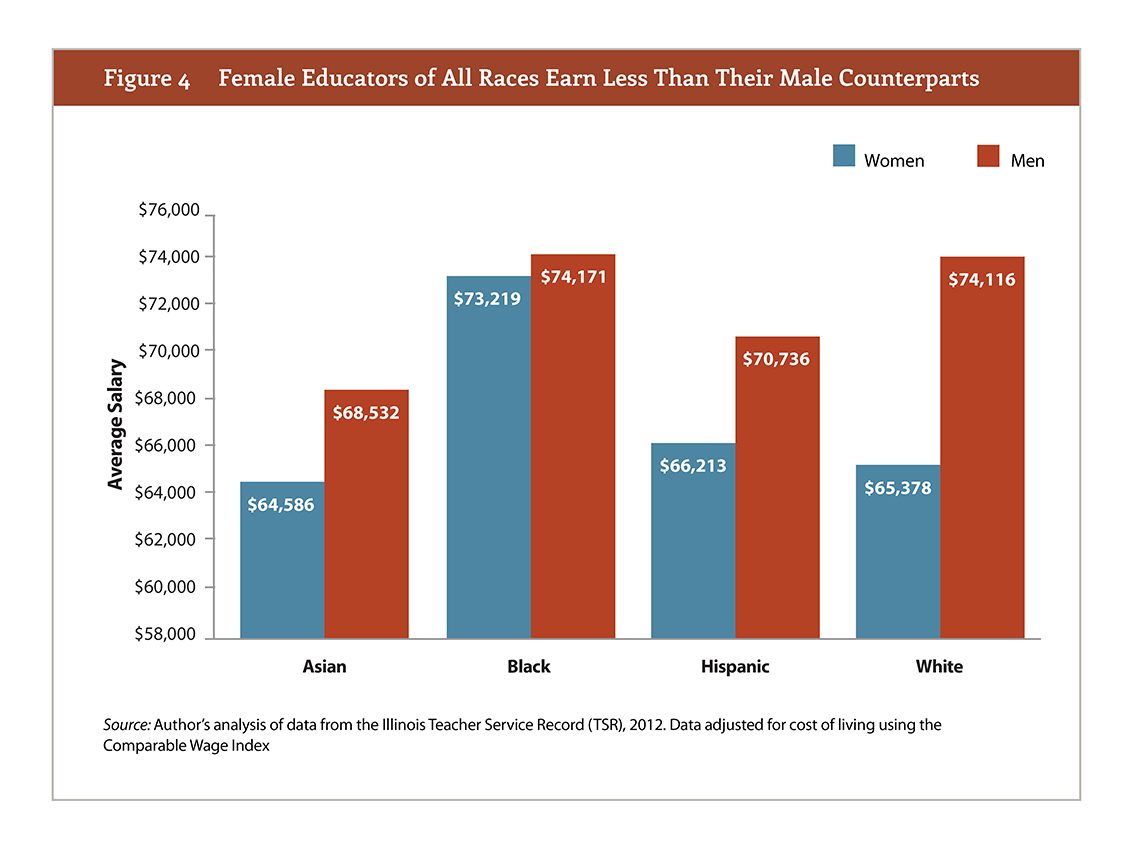

In our recent report we explored race-and gender-based salary gaps in Illinois. We found that women earn salaries that are on average $5,500 less than what men earn. As shown in the graph below, we also found significant gender-based pay gaps within races and ethnicities. Hispanic women, for example, earn on average $4,500 less in salaries than Hispanic men.

The story is less clear when it comes to across race salary gaps. At first glance, it appears that black educators are the highest paid, while Hispanic and white educators earn comparable compensation. But as my colleague Chad Aldeman and I demonstrated in a recent piece, digging deeper into the data reveals that black educators typically had to work longer and overcome significant barriers along the way to earning a higher salary.

We found that black educators are promoted and earn their master’s degrees much later in their career than white educators. This has a meaningful impact on their salaries since most district salary schedules assign the most significant pay bumps to additional degrees and administrative jobs. In Chicago Public Schools (CPS), black educators typically earn their master’s degree 3.5 years later than white educators, and those black educators who climb the leadership ranks do so five years later than their white colleagues. As a result, black educators need to work longer to earn the same aggregate compensation as white educators.

The silver lining for black educators is that they eventually acquire master’s degrees at higher rates than white educators and tend to work longer. Since teacher pensions are a function of salary and years of experience, this means that those who stick around earn a slightly greater reward in retirement. That may be cold comfort, however, since they had to suffer through many years of lower salaries and barriers to advancement. And, that doesn’t account for the many black educators who leave the profession without ever qualifying for a pension. Even those who remain may not ever make-up the gaps from earlier in their career.

We need to recruit educators of color, but we also need to retain them. Salary schedules, despite their uniformity, appear insufficient to guard against race-based disparities. Thus, as districts consider how to diversify their workforce, they must consider their recruitment pipeline AND their hiring and promotion practices to ensure that educators of color are treated fairly and enjoy equal opportunity. Otherwise, districts risk undermining their important diversity goals by asking educators of color to accept slower salary growth.