Colorado is on the verge of cutting teacher retirement benefits. We’re nine years into one of the largest stock market booms in history, and yet Colorado’s teacher pension plan faces a massive, and unmoving, unfunded liability.

The plan itself is asking for a cut in benefits for new workers, and earlier this month the state legislature announced its proposal. There are really three main questions: How much will benefits be cut for new workers? How much will costs rise and who will pay them? And should teachers be given a choice over their retirement plan, like other state workers in Colorado?

The debate over the first two questions are yet to play out in the legislature, but everyone is in agreement that something must be done.

There’s less agreement on the third question, but after analyzing the plans, it’s clear that not only should Colorado teachers be given an option to join the PERA –DC plan already offered to state employees, but that plan should be the default for all new teachers.

We know defaults matter tremendously. In the private sector, auto-enrollment in 401k plans, with the option to opt out, has significantly increased plan participation rates. Whether that’s due to trust in the default or simple inertia, workers will often go with the option that’s suggested for them. As a result, the default model should be the one that best serves the interests of the most workers.

The PERA-DC plan is a good alternative, and it’s not the typical 401k-style plan from the private sector. Employees contribute 8 percent of their salary, and employers chip in another 10 percent. It’s run by the state, which ensures members have good investment options with low fees.

While those contribution rates may seem high, they’re necessary because Colorado public-sector employees aren’t enrolled in Social Security. Without the basic floor of benefits that Social Security provides and that most Americans depend on, it’s even more important for the state to ensure its retirement plans give all workers a path to a secure retirement.

Even the current defined benefit plan isn’t meeting that goal. Due to steep teacher turnover rates and a back-loaded benefit structure, about 85 percent of Colorado teachers leave their service without adequate retirement savings.

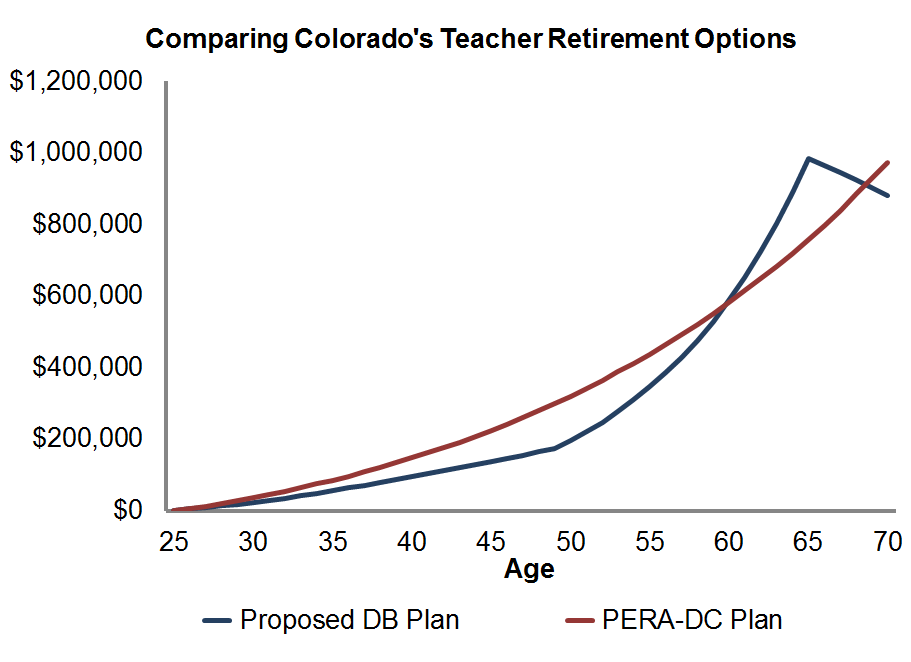

The proposed cuts would make the situation worse. The new defined benefit plan would be more back-loaded and leave more teachers exposed to inadequate retirement savings. The graph below shows what this would look like for a new, 25-year-old teacher. Even if the individual teacher was a slightly worse investor than the defined benefit plan, the defined contribution plan would deliver better benefits for the teacher’s first 34 years of employment. That is, she’d have to stay for 35 years before the value of her pension would finally surpass what she could have saved in the defined contribution plan.

Needless to say, the vast majority of teachers would be better off in the portable offering like the PERA-DC plan. At the very least teachers deserve the option to join the PERA-DC plan—after all, teachers deserve the same say over their retirement as state employees already have—but the numbers suggest lawmakers go a step further and make the PERA-DC plan the default option.

To be clear, my argument is premised on what’s good for teachers, but there would be other benefits as well. Crazy as this might sound, the PERA-DC plan is also cheaper, and it would halt the rising burden of unfunded liabilities. (Wisely, the proposed legislation also includes stabilization payments to the defined benefit plan to ensure that existing teachers and retirees are not harmed by the transition to a new plan.) If that sounds too good to be true, it all traces back to why Colorado is in this situation in the first place—its pension plan is so under-funded that it needs to keep cutting benefits for new workers. Under the status quo, costs keep rising, while benefits keep falling. Shifting new workers into a new plan would allow existing workers to keep their current benefits, while allowing new workers to opt into a better plan. That would be good for Colorado, and good for Colorado teachers.

Last week The New York Times ran an op-ed from Boston University law professor David Webber with the click-bait-y headline, "The Real Reason the Investor Class Hates Pensions." I work for a nonprofit and don't consider myself part of the "investor class," but Webber's piece is a mishmash of one solid argument undermined by several weak ones.

Webber's best and main argument is that public-sector pension plans provide a large source of capital to exert pressure on companies. According to his bio, Webber is writing a book on this topic coming out next month, and his op-ed is on firm ground when he points to instances of shareholder activism that led to more progressive policies and better corporate governance.

But he buries those examples amid a slurry of ad hominem attacks and a foggy understanding of what public-sector pensions are and do. Teacher pension plans are already in bed with Wall Street; the “retirement security crisis” narrative ignores data showing that elderly Americans are doing better and better; today’s defined benefit pension plans just don’t work that well for most teachers; and the costs of today's pension plans are enormous and are affecting schools and other public services.

But Webber’s biggest sin is he confounds the multiple roles that defined benefit pension plans play. They have many functions, among them:

Role #1: Provider of retirement benefits. When most people talk about public pension plans, they typically mean traditional "final average salary" pensions that deliver benefits through a formula based off years of experience and salary. As we and many others have documented, those formulas deliver benefits through back-loaded patterns that highly reward 20- and 30-year veterans while putting everyone else at risk of retirement insecurity. There are alternative models that offer much smoother benefit accumulation patterns that would protect all workers, including a type of defined benefit plan called a "cash balance" plan. The benefit accumulation function of retirement plans is distinct from other roles it plays.

Role #2: Investor. In addition to deciding how to deliver benefits, retirement plans also have to decide how to invest. They employ many individuals whose job is to decide how their state's pension plan should invest their capital. This is the role Webber seems to be most interested in, but it's distinct from the benefit role, and any retirement plan could make any investment decisions they choose. As an example, the California State Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS) could turn itself into the CalSTRS Investment Group and the state could require all teachers to invest their money through it. All of the political activism Webber highlights could continue (if that's what the members wanted with their investments), but the benefits could be delivered in some other fashion than the current design. In fact, CalSTRS already does this through a cash balance plan offered to certain types of school employees.

Role #3: Risk-taker. Under traditional defined benefit plans, the employer takes on most of the risks. The employer decides how much to save and where to invest, and bears the burden if their assumptions are wrong or if the stock market under-performs. Contrary to Webber, who implies that the "investor class" is somehow afraid of the role public-sector pension plans play in investments, my sense is that most people who care about public-sector pensions are primarily concerned about the risk-taking role. On one hand, taxpayers are worried about politicians who consistently over-promise and under-save for pensions, while workers like the idea of being protected from investment risk. From my vantage point, I find the cost arguments frustrating and at times mis-diagnosed, and I don't think workers fully appreciate the risks they do face, such as the risk that they might leave before they qualify for decent benefits, or the hidden costs that get passed down to them over time through lower salaries and worse retirement benefits. But again, there are ways to structure retirement plans to more adequately share risk between employees and employers.

Role #4: Provider of annuities. Webber doesn't mention it, but a fourth distinct role comes in the draw-down phase of someone's life. After they've accumulated assets during their working years, they need to figure out how to spend down their assets during retirement. Under current DB pension plans, the state takes responsibility for sending out monthly checks. Under most 401k plans, individuals have to make their own decisions about how much to withdraw and when. Any individual could decide to turn a lump sum amount of cash into an annuity that functions like a traditional pension, but states could also help out here by providing annuities to their workers as a way to help them make smarter decisions during the critical spend-down phase.

In order to think clearly about public-sector pension plans, we have to clearly distinguish what function we're talking about and why. Webber's main work appears to be focused on the "Investor" role as I've described it above, but his op-ed confused that role with other functions that pension plans play.

Since the vast majority of school districts employ uniform salary schedules, it seems reasonable to expect that educators should not experience gender-or race-based salary disparities’. Unfortunately, that is not the case. And to make matters worse, disparities in salary continue and grow through retirement.

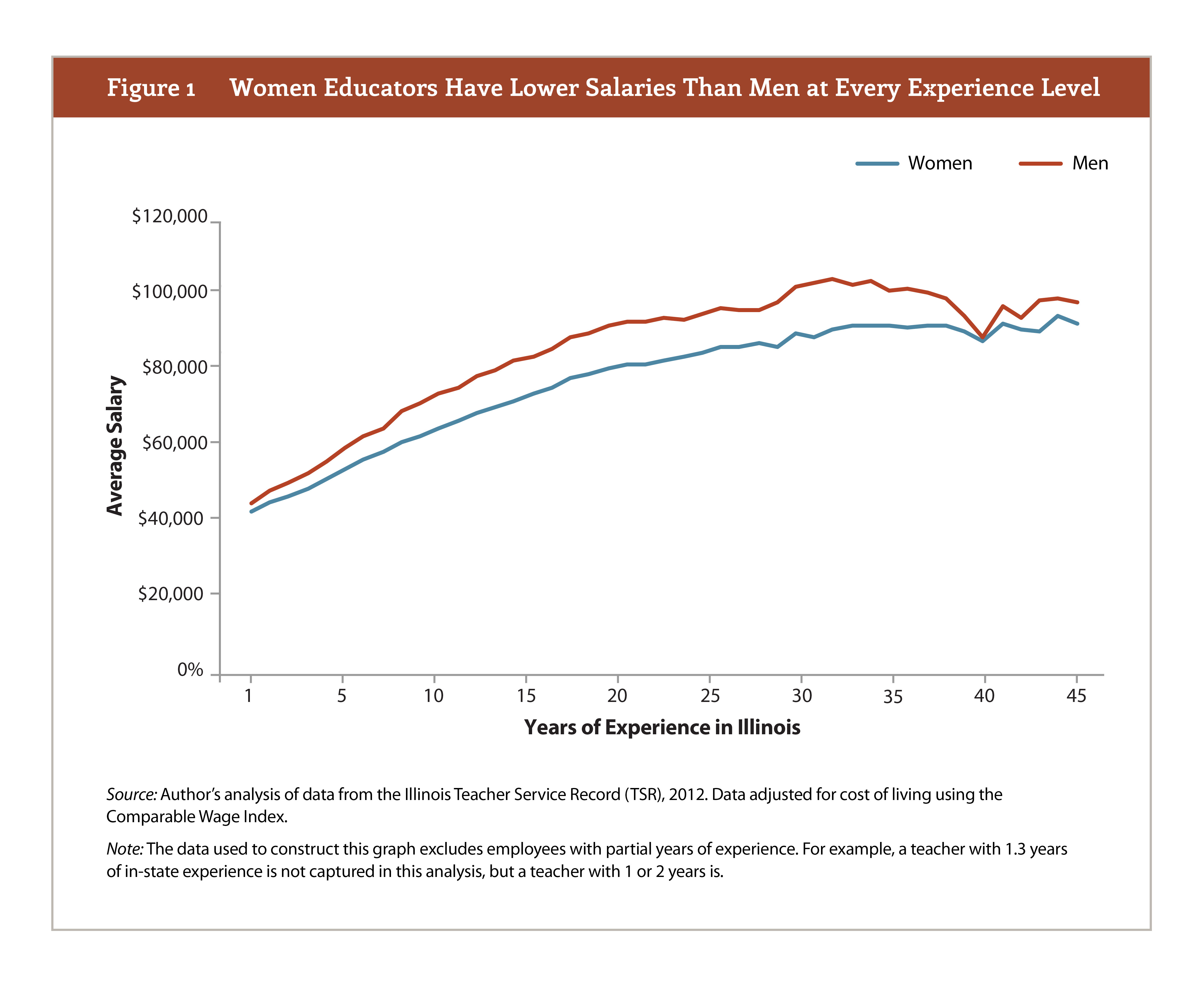

In a new report, we studied Illinois’ educator salary and tenure data, and found that women typically earn salaries that are $5,500 lower than their male colleagues. The salary gap exists as soon as women begin their careers. In year one, women earn on average $2,100 less than men. As shown in the graph below, the gender-based salary disparity persists and grows until educators reach their 30th year of service.

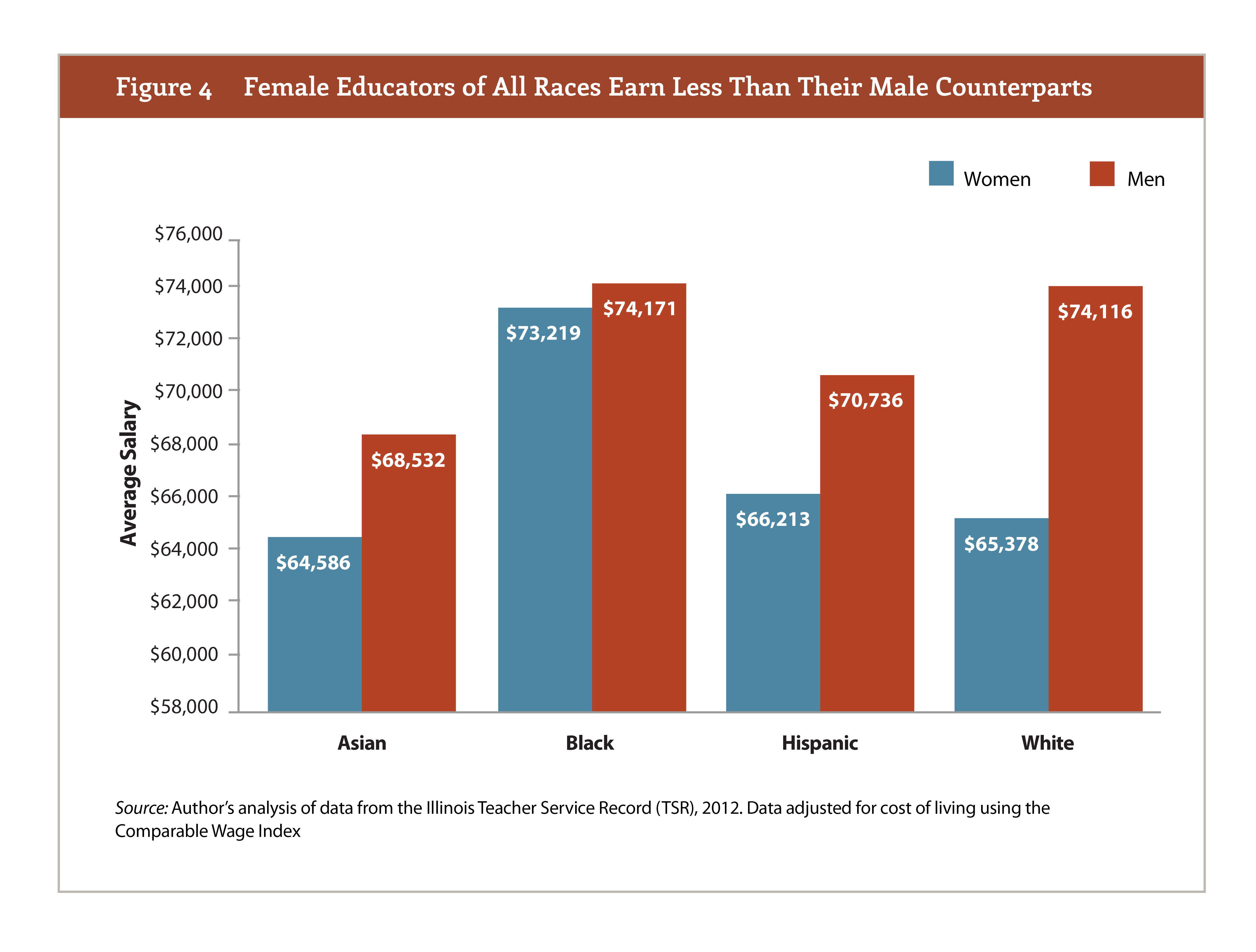

There are significant gender-based pay disparities within races and ethnicities. As shown below, women on average earn lower salaries than their male colleagues regardless of race. Hispanic men, for example, earn salaries around $4,500 more than Hispanic women. The largest gap is actually among white educators, while black educators have the closest average salaries. This is likely due to the fact that nonwhite educators primarily work in Illinois’ cities and suburbs, which pay the highest salaries in the state.

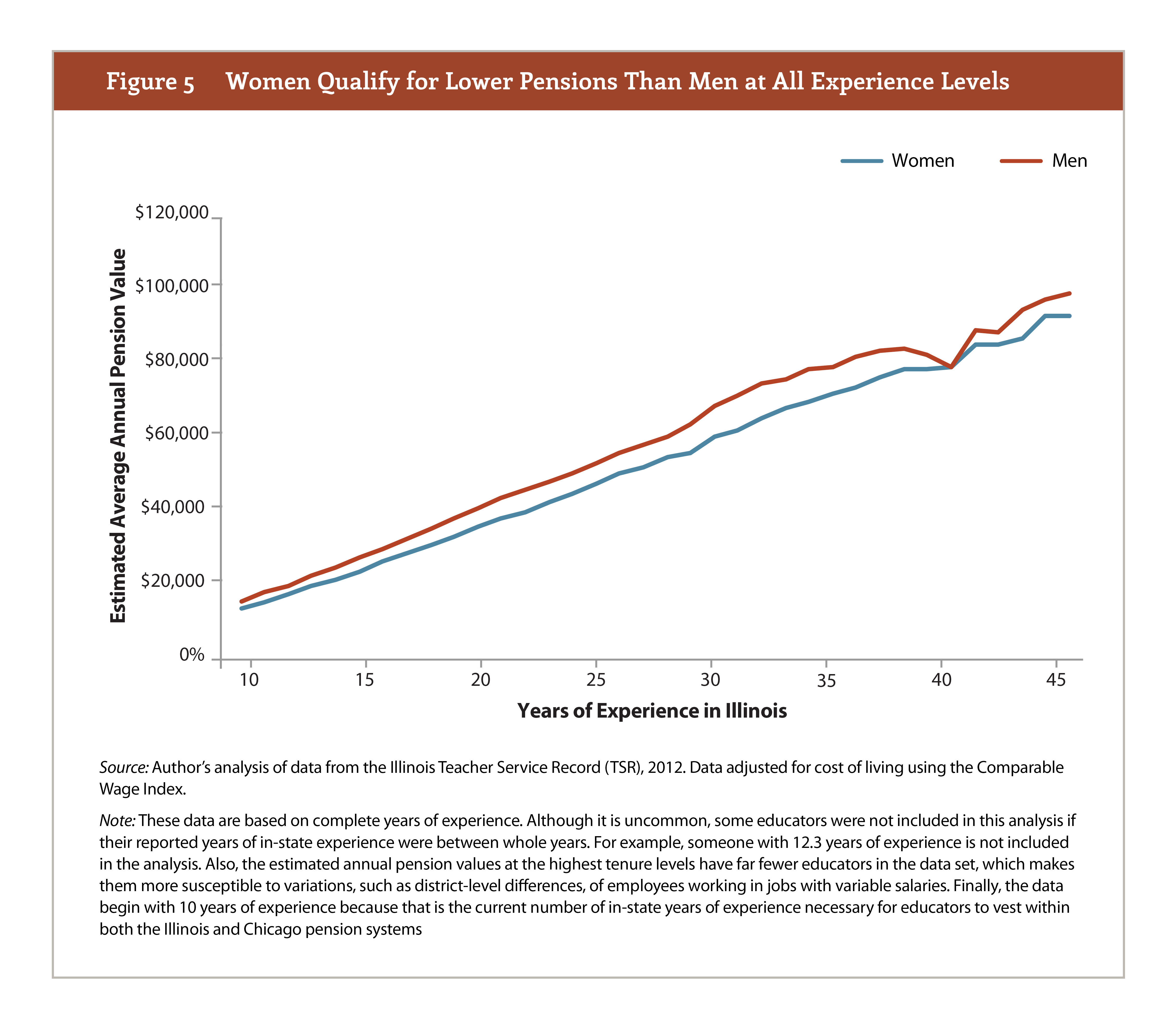

But unfortunately, salary gaps only tell part of the story. These inequities echo in retirement, resulting in even lower overall compensation for women compared with men. In fact, by excluding retirement wealth from analyses of gender-and race-based disparities in pay, we overlook the full extent of the problem. As shown in the graph below, women also earn less valuable pensions at every experience level.

After about 30 years of experience – a full working career – women’s estimated average annual pension value is $8,000 less than her male colleagues. After 10 years, men will have amassed $80,000 more in total retirement wealth than women who worked the same number of years. This pattern holds regardless for all races and ethnicities except for black educators. Black women early slightly larger annual pensions, which is likely due to the fact that they work longer and work exclusively in high-paying districts. Finally, while it is true that women tend to live longer than men, longer life does not eliminate the pension wealth gap, and it also requires women to live well into their 80s and 90s.

States and districts must recognize that large pay and retirement wealth gaps exist despite the use of uniform salary schedules. To address these problems, states and districts should consider:

- Analyzing their data to determine if they pay educators similar salaries for similar performance.

- Assessing whether an educator’s salary trajectory suffers unduly when they need to take time off, such as new or expecting mothers, to care for their family.

- Considering their rules on where incoming educators are placed on the salary schedule and whether provisions capping the number of years of credited experience disadvantages certain groups of workers.

- Evaluating promotion and leadership pipeline data and practices to identify race-or gender-based inequities.

To learn more about gender-and race-based educator salary and pension inequities, read the full paper here.

For the last nine days, West Virginia teachers have been out on strike over concerns about salaries and healthcare benefits. Much of the press coverage on the strike has focused on West Virginia's low ranking in average teacher salaries (see examples from The New York Times, USA Today, The Washington Post, CNN, Vox, etc.).

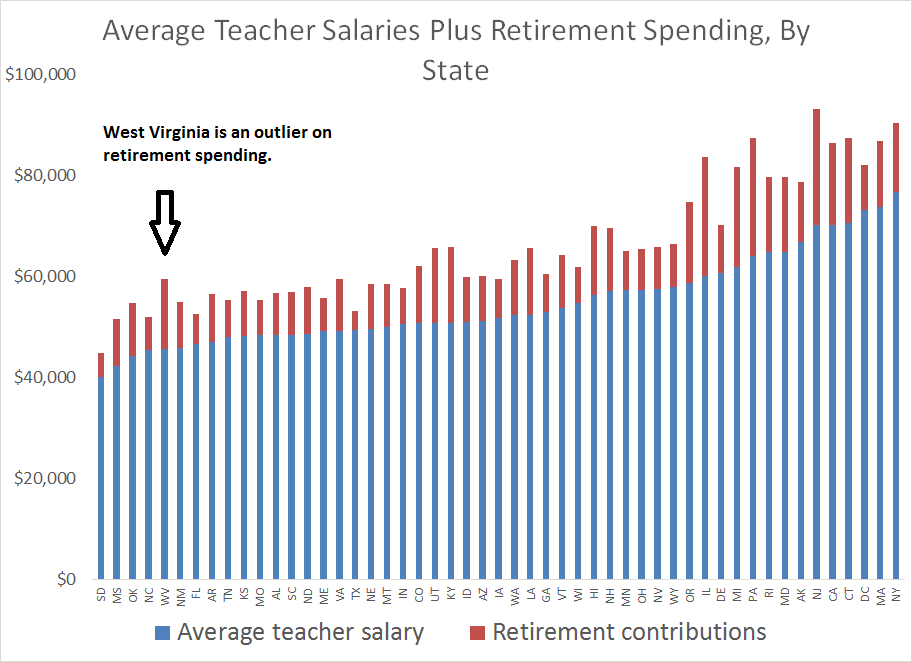

While it's true that West Virginia has low average salaries, this statistic misses out on lots of other things. For example, I've written before about how growing retirement costs are eating into teacher salaries, and it turns out West Virginia is a prime example of this. In fact, while West Virginia ranks in the bottom five states in teacher salaries, it ranks in the top five in terms of retirement costs (most of that money is going toward paying down unfunded liabilities, but it's a real expense incurred by the state and its school districts). Overall, West Virginia climbs to 32nd in terms of salary plus retirement costs. That's a very different story than the one being told by the media.

Of course, this also doesn't get into cost of living. West Virginia lands in the middle of the pack on cost of living, and if we adjusted the raw salary figures based on how far $1 would go, West Virginia teacher salaries would rank even higher.

None of this is to make a judgment about how much West Virginia teachers should be paid, but that argument shouldn't hinge on the "average teacher salary" metric. Without looking at all forms of compensation or adjusting for cost of living, average teacher salary rankings don't tell us all that much.

Taxonomy:In February Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner announced his latest budget proposal. One of his money-saving ideas is to cut $2 billion in state spending by shifting teacher pension costs to school districts. While this plan has some merits, there nevertheless is a lot to dislike about this approach.

In every state, pension benefits and pension contributions are made as a percentage of educator salaries. And since school districts set salaries, it makes some sense that they should carry the responsibility of financing the resulting pension costs. The issue, as Governor Rauner points out, is that districts can establish generous back-end salaries to attract educators, knowing that the increase in pension costs from those higher salaries will be picked up by the state. This disconnect can become an expensive cycle in which districts raise wages to compete for educators, leading to a tragegy of the commons.

There are a few problems with this argument.

For one, there is a case to be made that districts, particularly those serving a lot of students living in concentrated poverty, need additional funds to encourage effective teachers to work in more challenging schools. And while the new state school funding formula will send additional money to high-poverty districts, it is unclear if it will be enough to offset the new pension costs.

Also, it is disingenuous to suggest that lavish salaries and pension spiking are the main or even a primary reason Illinois’ teacher pension system is in dire financial straits. To be sure, higher salaries means higher pension payments. However, there are greater drivers of burgeoning state pension debts, such as the state legislature’s long history of underinvesting in the pension fund as well as increasing benefits during bull markets without ensuring long-term solvency.

To avoid pushing out other education expenses to cover pension costs, communities could elect to raise property taxes. But of course, levying new taxes is politically and economically challenging. And even if a district were to raise new revenues, that would likely exacerbate existing inequities in school funding. Low-wealth districts will likely struggle to raise revenue to avoid pushing out other educational expenditures, while wealthier districts have the capacity to increase revenue more easily and avoid that trade-off.

There is no denying that something must be done to address the more than $70 billion in teacher pension debt Illinois is carrying. But shifting the cost to districts and hoping that they can make up the difference is wholly insufficient and could cause greater damage to local districts and schools.

The unfortunate truth is that the state of Illinois only has itself to blame for this problem. Getting out of it will take state-level solutions that, at the very least, provide new educators the option of opting into a different retirement savings plan that is actually more productive than the pension system for the typical teacher. Forcing districts and schools to raise local taxes or forgo other spending while cutting state pension funding may sound like a neat trick, but if anyone should be tightening their belt, it’s the state.

Taxonomy:Earlier this week the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce released a new report looking at the gender wage gap. They found that even with the same education credentials and work in the same occupation, women earn only 92 cents for every dollar a man earns. Even when women choose the most lucrative majors, men still are paid more. In the words of the authors, “women can’t win.”

In a forthcoming report looking specifically at teachers and administrators in Illinois, we found similar results. After digging into the data, we found that female educators on average earned 92 percent of what their male educators do. Our analysis shows that gender pay gaps exist even when narrowing in on certain roles and regardless of educational attainment.

Stay tuned for more—or reach out to me at max-dot-marchitello-at-bellwethereducation-dot-org to receive an alert when it comes out.