How much do teacher pension plans cost? How have those costs changed over time?

Those may seem like simple questions, but there aren’t perfect data sources to answer these questions. At the national level, the U.S. Census Bureau tracks total benefit spending by states and school districts, which does include retirement costs but also includes healthcare and other employee benefits. The Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks national figures but only reports the data in terms of percentages and a per-hour basis.

Luckily, the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College (CRR) has done the yeoman’s work of collecting comparable data from state pension plan financial reports. The raw data still aren’t perfect to answer the questions I posed above—many states include teachers and other education workers alongside other public workers in the same plan—but with a little bit of work, I was able to narrow the data to look solely at teachers and other educators. (For simplicity’s sake, I’m going to use the term “teachers” throughout the remainder of the post, but the numbers also include other school support staff, principals, superintendents, and central office staff.)

With that throat-clearing out of the way, what do the numbers say?

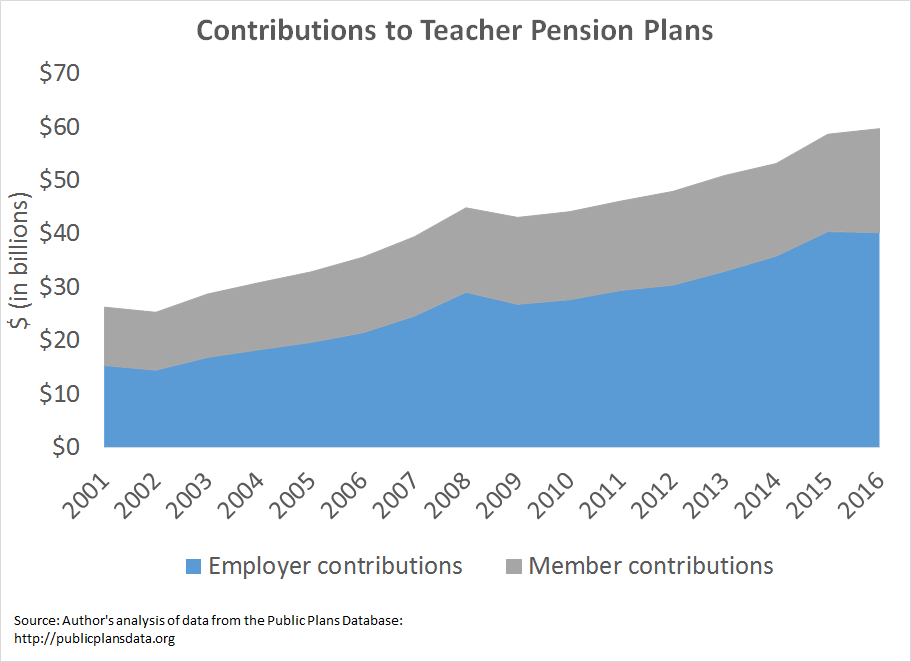

Over the last 15 years, state and district spending on teacher pensions is up approximately 261 percent. Meanwhile, states have cut teacher retirement benefits and asked teachers to pay more for worse benefits.

I’ve written about these issues recently for particular states, but it’s also worth zooming out to look at the national picture. Nationwide, states and districts now spend about $40 billion on teacher pension costs, up from $15 billion 15 years ago.* Over a period where states struggled to invest in K-12 education, rising pension costs have meant even fewer dollars making it into classrooms.

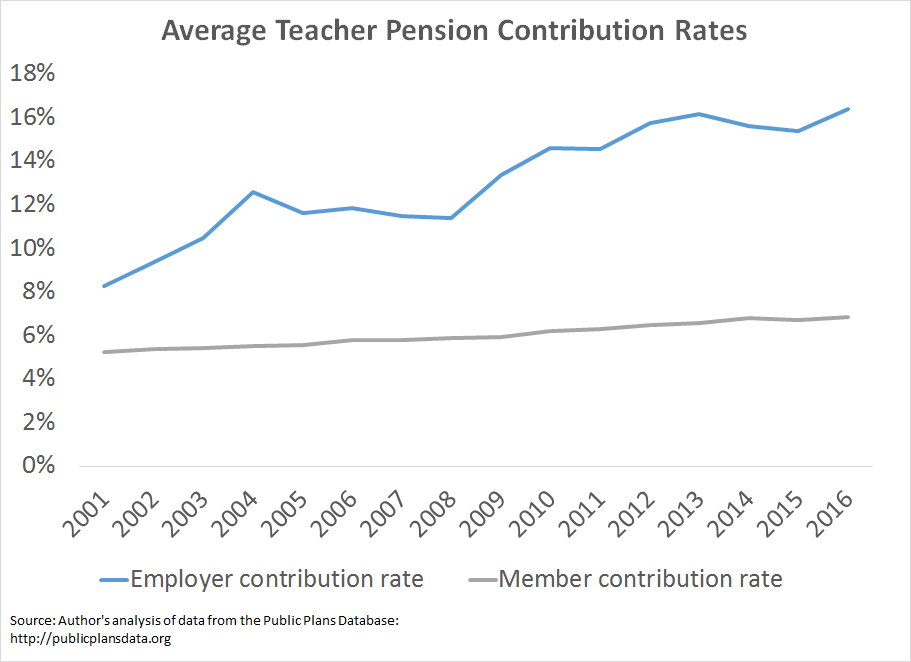

Another way to look at pension costs is to look at contribution rates. As the next graph shows, mandatory member contributions have increased over time, from an average of 5.2 percent of salary up to 6.8 percent. Again, this has happened at the same time states have been cutting benefits for new teachers. Teachers are paying more for less.

Worse, the employer actuarially required contribution rates, the rate that actuaries estimate will be needed to pay for all the future promised benefits, has doubled from 8.3 to 16.4 percent.

These graphs don’t even include Social Security. If you factor in Social Security contributions, it would appear as if teachers have enormous pots of money being set aside for their retirements.

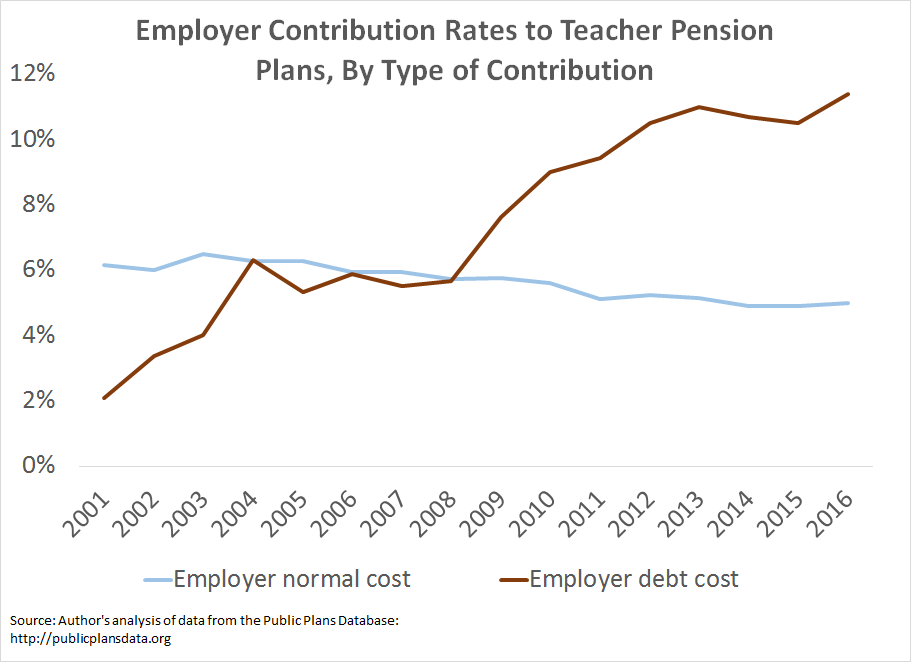

I say “appear” because that’s not how teacher pension plans work. Unfortunately, the increase in pension contributions is entirely due to paying for past pension promises that have not been adequately saved for, not to pay for actual benefits for teachers. States break down their contributions into two rates, the “normal cost” of benefits, which is the actuaries’ estimate of how much the benefits are worth on average, and the cost of paying down any accumulated debt, known as the “amortization cost.” As the graph below shows, the average normal cost of teacher retirement benefits has fallen from about 6.2 percent of salary to slightly less than 5 percent. These are averages across all members in a given plan; as states have cut benefits for new teachers, the figures would be even lower if we had accurate data about how much each of these tiers are worth.

Meanwhile, the amortization costs, aka the debt cost, of teacher pension plans have risen from an average of 2 percent of teacher salaries to more than 11 percent. To put it crudely, it’s as if states failed to make sufficient payments on their credit cards or their home mortgage, and now their interest costs have ballooned.

These costs will not go away any time soon, and states will need to think differently if they want to see any future changes. Left unaddressed, the mountain of debt is likely to keep growing, and teachers will see more and more of their compensation going toward paying off past pension debts instead of going into their pockets.

*Note: The numbers in this post are meant as estimates. They start with data from the Public Plans Database, with a few adjustments. About half the plans in the database include educators and non-educators alike, so in order to get a closer estimate of the education share, I applied weights used by the National Council on Teacher Quality which are based on the percentage of each plan’s membership who are educators. For most states, the data run from fiscal year 2001 through fiscal year 2016, but data were not available for all states and all years. A few states were missing random years of data, in which case I used the average of the years before and after. I took out Kentucky entirely, since it was missing all years prior to 2014. And a couple states, notably New Hampshire and Oregon, were missing data for the earliest years in this time period. For those states, I simply applied the later rates going backwards.

Taxonomy:The state pension plan funding gap is well-documented -- according to Pew, the gap between the promises states have made for public employees’ retirement benefits and the money they have set aside to pay these bills was at least $1.4 trillion in fiscal year 2016. For a blog dedicated to providing high-quality analysis and information on teacher pensions, it’s clear that there is a problem.

Let’s talk solutions.

While traditional, back-loaded pension plans fall short of providing adequate retirement benefits to all members, there are better options. And, contrary to a public debate that often pits pensions against 401ks, there are other alternatives that would better balance the needs of employers and employees.

As one alternative example, the Texas Municipal Retirement System (TMRS) is legally a defined benefit cash balance plan. As of December 2016, 872 Texas cities had opted into the plan, covering 108,500 active members and 59,000 retirees. Participating cities select an employee contribution rate (of 5, 6, or 7 percent), an employer match (1:1, 1.5:1, or 2:1), and the contributions go into a worker's account. The plan invests the money and guarantees a rate of return of at least 5 percent. This provides a more portable benefit with a steadier accumulation of assets than the typical defined benefit plan.

The plan also helps employees once they retire. When the employee reaches retirement eligibility, the money in their account is annuitized into regular monthly paychecks. These paychecks allow for sustained monthly income, mirroring the benefits and stability of a traditional pension plan without the back-loaded accumulation under traditional pension plans. (See more details of how the plan works here.)

No plan is perfect. Here, employees might be able to earn higher return in a defined contribution, 401k style plan, but to do that, they would have to sacrifice the guarantee. Employers still bear some risk, but it’s smaller than under a traditional defined benefit plan. Still, this system allows employers some level of customization, and the portability piece makes it appealing to employees. TMRS, a defined benefit cash balance plan, is just one of many retirement options that could better address the cost and portability problems that are prevalent in the plans offered to public school teachers.

By now it's become something of a joke on social media, but earlier this month MarketWatch tweeted that, "By 35, you should have twice your salary saved, according to retirement experts." The original source for the tweet is a set of calculations by Fidelity Investments. It may be funny to joke about--my favorites involve acquiring a wide variety of Tupperware, plastic bags, and electric cords--but the Fidelity targets were an earnest attempt to estimate how much people should have saved at various ages in order to be on a path to a secure retirement.

The Fidelity targets are ambitious, but they're not crazy. They start with the assumption that people should aim to replace 45 percent of their income every year in retirement. That level of savings, plus Social Security, should afford someone to comfortably retire at age 67. Fidelity works backwards from there to estimate how much people should have saved at every stage of their career. The targets are framed as a percentage of income on the assumption that people should aim for a similar lifestyle in retirement as they enjoyed during their working years.

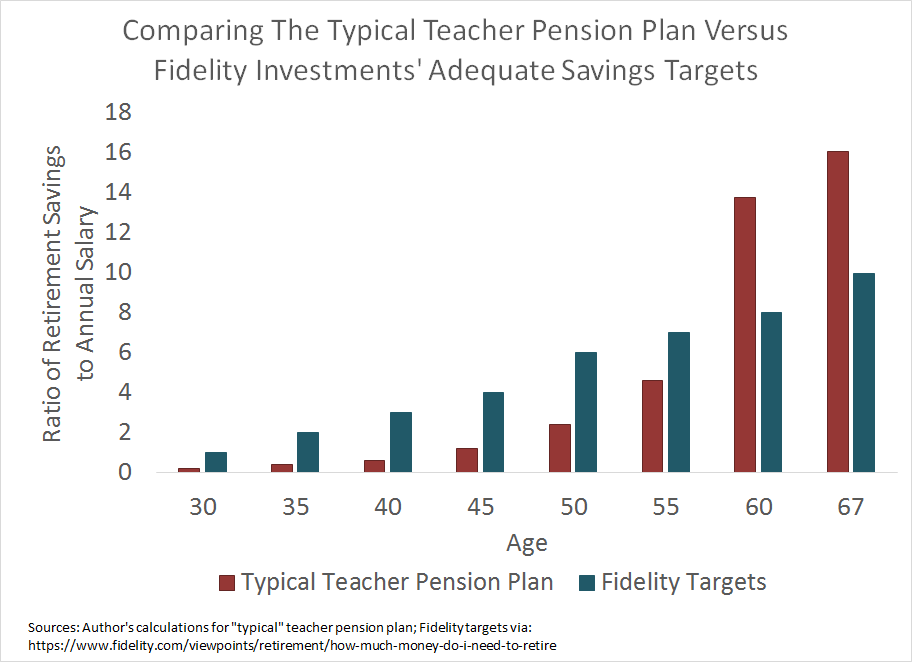

Given the perception of teacher pensions as being extremely generous, I set out to compare the typical teacher pension plan against the Fidelity targets. Using data from the National Council on Teacher Quality, I created a "typical" teacher retirement plan and then compared how assets accumulate for a typical public school teacher versus what Fidelity recommends.

As the graph below illustrates, the typical state-run pension plan forces teachers to suffer from years of low savings. If a teacher leaves the profession short of a full career, she may qualify for a pension, but it won't be large enough to provide for a comfortable retirement. To reach the same level of retirement security, ex-teachers will have to save more in later years, retire later, work longer, or depend on family members.

The graph also shows the opposite end. For the fraction of teachers who do stay for a full career, the typical pension system works fairly well. If they stick it out and continue teaching well into their 60s, their retirement income will start to beat out the Fidelity targets. (Due in part to the way the plans are structured and when they allow teachers to retire, most teachers, even full-career teachers, retire well before their mid-60s.) Still, this level of retirement security is only provided to those who remain as teachers in one state for their entire careers. Depending on the state, that's only 15-20 percent of incoming teachers. The rest fall short.

Public school teachers could have their own personal investments that might make help make up the difference, but the graph above may be under-selling the issue somewhat, since Fidelity's targets take Social Security for granted. About 40 percent of public school teachers do not have Social Security, so they're even more vulnerable to back-loaded teacher pension plans.

As the jokes made clear, many people find the Fidelity targets unrealistic. And they may be for lots of young people facing other financial pressures. But they're simply one way to gauge retirement readiness. And public school teachers aren't passing the test.

Taxonomy:How do retirement plans affect teacher recruitment and retention? What happens to the teacher workforce when states change their retirement plans?

Of these two questions, it’s much easier to study how pensions affect retention, because retention is a measure of people who are already in the profession. For early-career teachers, pensions don’t seem to have much effect at all. When we looked at state assumptions on worker turnover, we discovered that no state assumes teachers will change their behavior in order to qualify for a pension benefit. That is, new teachers don’t stick around just for a pension. There is evidence of a “pull” effect as teachers approach normal retirement age, the age at which they can begin collecting an unreduced pension benefit. Veteran teachers are aware of the pension system and will stick it out a few more years to hit their milestone. But this effect seems to occur quite late in a teacher’s career, and few teachers make it to that point.

After teachers reach normal retirement age, there’s a large "push" effect that nudges them out of the classroom and into retirement. All told, pensions seem to have a mild retention effect, but mainly on late-career veterans, and they also push veteran teachers out of the classroom at relatively young ages. On net, switching to a different type of retirement plan is likely to have only a limited effect on teacher retention.

But what about teacher recruitment? Do retirement plans play a role in getting potential educators into the classroom in the first place?

Pension plan effects on recruitment are harder to pin down, because those questions are asking about the behavior of potential teachers. A recent study from Matthew Kraft, Eric Brunner, Shaun Dougherty, and David Schwegman on teacher accountability reforms and the supply of new teachers shines at least a partial light on this issue. The paper is primarily focused on whether teacher tenure and teacher evaluation reforms affected the supply of new teachers, but one of the variables Kraft et al included was the employee contribution rate into state pension plans. The authors did not look at other pension reforms going on at the same time, but employee contribution rates should be one of the most salient. And yet they did not find employee contribution rates had an effect on the supply of new teachers.

This finding offers at least one piece of evidence that new teachers don't pay that much attention to retirement issues. Based on our read of the broader literature on retirement and worker retention (see discussion here, for example), it’s clear that workers want to know they have some retirement plan, but the specifics of that plan are not likely to drive their decisions as much as salary, location, or other intangible factors might.

There are two more issues that are specific to the teaching profession. One is that the vast majority of teachers are enrolled in statewide retirement plans. That means school districts aren’t competing for teaching talent with other districts in their state on the basis of retirement benefits. If there’s a change in the retirement plan, it affects the entire state. For a change in retirement plan to affect the supply of new teachers, those would-be teachers would have to cross state lines or give up on their chosen profession. Private schools are also not competitors here, because private school retirement benefits tend to be far less generous.

Two, the typical teacher pension plan is enormously complicated. Even if teachers valued the structure of a defined benefit pension plan, they would have to be exceptionally well-versed in financial modeling to factor in all the variables that determine someone’s ultimate benefit. Pension plans pay actuaries to do this, and there’s a whole body of research trying to explain how workers accumulate benefits under pensions plans. Unlike in a 401(k) plan where a worker can easily understand and compare employer contribution rates, the pension plans offered to most public school teachers are much harder to quantify and evaluate.

The Kraft et al paper is just one piece of evidence, but the findings suggest that pension reform need not harm the supply of incoming teachers. If anything, updating teachers’ retirement options could even free up resources to raise base salaries, which may ultimately affect the teacher workforce more than retirement benefits ever can.

The fact that pensions aren’t an effective tool to shape the teacher workforce doesn’t mean states should eliminate all retirement benefits. On the contrary, recognizing that fact frees up policymakers to focus on the question of whether all workers are on a path to a secure retirement. It may be interesting to think about whether pension plans affect teacher behavior, but ultimately retirement plans should be designed for workers, not their employers.

In honor of Teacher Appreciation Week, we think one of the ways states could thank teachers would be to make sure they all have secure, portable, sustainable retirement benefits. Unfortunately, too many teachers do not. To help illustrate why that’s not happening, consider six ways states make it harder for teachers to qualify for secure retirement benefits, as told through the lens of some of the most memorable, fictional teachers and educators:

Transitioning: State pension plans require teachers to remain as a teacher in that state for five or even 10 years to qualify for a pension at all. But according to the pension plans themselves, about half of all new teachers don’t make it that far. Teachers like Jessica Day (Zooey Deschanel) in New Girl and even Laura Ingalls Wilder (loosely fictional, I know, work with me) ultimately leave the profession after only a few years, and thus without any retirement benefits.

Portability: In most states, teacher pension benefits are not portable, and states impose barriers for teachers who want to transfer their benefits to other professions or other states. In contrast, Professor Indiana Jones and other higher education teachers typically have more portable retirement benefits, even if they work at public colleges and universities.

Breakeven: For the majority of teachers, what they can anticipate in retirement benefits will actually be worth less than what they contributed to the system while they were in the classroom. Viewers may not feel sorry for the plight of Matthew Broderick in Election, but he loses more than his job and his dignity over the course of the film. In Nebraska, where Broderick’s character taught, only 12 percent of teachers stay long enough to earn a pension worth more than their own contributions.

Social Security: What do Erin Gurwell in Freedom Writers (played by Hilary Swank), Mr. Hand in Fast Times at Ridgemont High (Ray Walston), and Nona Alberts in Won’t Back Down (Viola Davis) have in common? All three taught in California, a state where teachers do not qualify for Social Security benefits. They aren’t alone. Teachers in 15 states (Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nevada, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Texas) and the District of Columbia go uncovered.

Leadership: Most states enroll all educators — teachers, principals, and superintendents — into one state pension plan, and it's usually named the "teacher" plan. But the largest payouts from "teacher" pension systems aren't actually going to teachers. Instead, the biggest winners are long-serving, highly paid administrators. For example, while teacher Edna Krabappel might earn a decent pension for her years of tolerating Bart Simpson, Principal Skinner and Superintendent Chalmers likely do even better. In this way, pension formulas amplify the gender wage gap

Longevity: This is morbid, but pensions are only beneficial so long as you don’t die. In October Sky, Miss Riley (played by Laura Dern) accepts a low West Virginia teacher salary in exchange for an expensive pension benefit that never comes. Or, spoiler alert: Several of Hogwarts’ Defense Against the Dark Arts professors (Quirinus Quirrell, Gilderoy Lockhart, Remus Lupin... all of them?) don’t make it into retirement.

These are all fictional characters, but they help illustrate common problems with teacher pension plans. We should work to make sure teachers don’t have to suffer from these same problems in their real lives.

Student loan debt passed the $1 trillion threshold a few years ago. And now, credit card debt has also reached that unfortunate milestone. This rapid growth in debt occurred despite the fact that wages, for the most part, have remained stagnant for decades. To reverse this trend, financial literacy and planning will be increasingly important.

A new study from WalletHub finds that financial literacy and sound financial practices vary widely by state. According to WalletHub’s analysis based on their own financial literacy survey as well as other measures of financial tools and habits, these are the most and least financially literate states in the country:

It is a problem, particularly for teachers, that financial literacy and planning varies so widely since teacher retirement plans require a good deal of financial savvy to understand.

That may not be apparent at first glance. The vast majority of public school teachers in this country are enrolled in state-run defined benefit (DB) pension plans. Teachers are automatically enrolled in those plans, and all investment decisions, including how much to contribute and how to invest those contributions, are made by the states.

But the benefit formulas are actually quite complicated, and there's mounting evidence that the plans fail to provide most teachers with benefits sufficient to meet their retirement needs. Due to different decisions in state legislatures, pension rules vary from state-to-state, leading to different vesting periods, variation in teacher contribution rates, and differences in benefit quality.

Furthermore, the majority of state pension funds are non-portable. This means that they cannot be taken across state lines if an educator moves. The lack of portability can dramatically, and negatively, affect a teacher’s long-term retirement savings. And finally, around 1 million teachers are uncovered by Social Security, which leaves them more dependent on their own personal saving.

In short, teachers may think that because they are enrolled in a pension system their retirement is taken care of for them by the state. But, that only works for a handful of educators. The rest have to figure out whether they’re covered by Social Security, how to make up for years of low savings rates for the pension fund by the state, and what to do if they leave teaching or cross state lines. None of these are easy decisions, and a recent a study of Illinois educators suggests many are doing it “wrong,” at least in financial terms.

Although it does not deal directly with teacher pensions, WalletHub’s study is a useful prism through which to understand the financial challenges facing teachers. And while much could be done to provide educators with better retirement options, states need to, in the meantime, do more to educate their workers about the true value of their pension at various points in the career and what to do when they leave the profession.