A teacher with split Social Security coverage emails us with a question about how to maximize her retirement:

Here is a little background on my question. I entered teaching later in life than is typical. I worked in the corporate world for over 10 years before pivoting to teaching. Thus, I already had the 40 quarters required for Social Security. I understand that my 10+ years of teaching service do not count towards Social Security, but I don't understand how I can have her 40 quarters taken away by entering teaching. It's almost beginning to feel like it may be in my best retirement interest to go back to the corporate world.

Can you point me in a direction that would give me some sort of clarity?

Thank you,

--Career Switcher

Hi Career Switcher,

I have two pieces of good news for you. The first is that you will not have all of your Social Security benefit taken away. Given your 40 quarters of contributing toward Social Security, you are entitled to a benefit when you reach the retirement age.

The second piece of good news is that you may be better off than your colleagues in terms of pension benefits. Because you are closer to reaching your state's retirement age, your pension is more valuable than your younger colleagues with the same amount of experience. See here for a longer explanation.

But now for the bad news. Yes, your Social Security benefit may be reduced under what's known as the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP). The exact answer to your question depends on how long you taught without Social Security coverage, how much money you earned (and thus contributed to Social Security) while there, and the comparison between the value of your pension and your Social Security benefit. For more detail about how the WEP works, see this two-pager from the Social Security Administration with an explanation and the methodology behind the calculation. Although it changes slightly every year, the maximum WEP penalty in 2020 is $480 a month in retirement.

However, the WEP cannot reduce the value of your Social Security by more than half of your pension amount. That provision means that the WEP does not apply to anyone with only a small pension.

To your ultimate question, it's hard to know whether you would be better off going back into the corporate world for a few years. That would depend on the salary in either job, how many years you have until retirement, and how many years you plans to continue working.

You should consult a qualified financial advisor to run the numbers, but from a purely retirement wealth perspective, it's possible you may earn more with the combination of Social Security (even with a WEP penalty) plus a teacher pension benefit rather than trying to maximize your Social Security benefits.

This may be a longer answer than you were looking for, but hopefully it's helpful, and all the best,

~Chad Aldeman

Note: This is a real question submitted to us. We have removed all personally identifiable information, but we believe there's a value in sharing frequently asked questions to benefit others with similar concerns. If you have a question you would like answers to, please feel free to email us at teacherpensions@bellwethereducation.org. Please note that by submitting a question to us, you agree to let us share the question and our answer publicly here on the TeacherPensions.org blog.

At what age can teachers retire?

The answer to that question depends on the state, the date the teacher began their employment, their age, and their years of service.

The table below is intended as a helpful tool for teachers to understand the rules that might affect them. For each state pension plan, the table provides the normal and early retirement ages applicable to teachers based on their hire date and relevant benefit tier.

Nearly every state has multiple tiers with different benefit rules that depend on the teacher’s start date. For each tier, the plan’s “normal” retirement age reflects the point at which the teacher can retire and begin collecting his or her full benefit. Retirement ages are generally expressed as a combination of age and years of service. For example, Alabama allows its Tier I employees to retiree with full benefits at age 60 once they have 10 years of service, or any age once they attain 25 years of service. In the table, these are marked as “60/10” and “Any/25,” respectively.

Many states also offer teachers the option to retire early with a reduced benefit. For example, Arizona allows teachers to claim a reduced pension benefit beginning at age 50 for those employees with five or more years of service. The farther away the worker is from the plan's normal retirement age, the larger the reduction they face. Those reductions are permanently locked in once the employee begins collecting their benefit.

See the table below for the normal and early retirement ages in your state. For more information, check out our state pages, or contact your state's pension plan.

State

Plan Name

Tier

Normal Retirement Eligibility: (Age/Years of Service)

Early Retirement Eligibility: (Age/Years of Service)

Alabama

Teachers' Retirement System (TRS) - Tier 1

Hired before January 1, 2013

60/10; Any/25

Alabama

Teachers' Retirement System (TRS) - Tier 2

Hired on or after January 1, 2013

62/10

Alaska

Alaska Teachers Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 1990 and before July 1, 2006

60/8; Any/20

55/8

Alaska

Alaska Teachers Retirement System

Hired after July 1, 2006

N/A

N/A

Arizona

Arizona State Retirement System

Hired before Jan. 1, 1984

60/10; 65/1; Age + YOS = 80;

50/5

Arizona

Arizona State Retirement System

Hired on or after Jan. 1, 1984 and before July 1, 2011

62/10; 65/1; Age + YOS = 80

50/5

Arizona

Arizona State Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 2011

65/1; 62/10; 60/25; 55/30

50/5

Arkansas

Arkansas Teacher Retirement System

60/5; Any/28

Any/25

California

California State Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS)

Hired before January 1, 2012

60/5

50/30; 55/5

California

California State Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS)

Hired on or after January 1, 2013

62/5

55/5

Colorado

Public Employees' Retirement Association (PERA)

Hired before July 1, 2005; vested on January 1, 2011

50/30; 55 and AGE + YOS = 80; 65/5

50/25; 55/20; 60/5

Colorado

Public Employees' Retirement Association (PERA)

Hired after June 30, 2005 and before January 1, 2007; vested on January 1, 2011

Any/35; 55 and AGE + YOS = 80; 65/5

50/25; 55/20; 60/5

Colorado

Public Employees' Retirement Association (PERA)

Hired after December 31, 2006 and before January 1, 2011

Any/35; 55 and AGE + YOS = 85; 65/5

50/25; 55/20; 60/5

Colorado

Public Employees' Retirement Association (PERA)

Hired after December 31, 2010

Any/35; 58 and AGE + YOS = 88; 65/5

50/25; 55/20; 60/5

Connecticut

Teachers' Retirement Board

All

60/20; Any/35

60/10; 55/20; Any/25

Delaware

Delaware State Employees' Pension Plan

Hired on or after Jan. 1, 1997 and before Jan. 1, 2012

62/5; 60/15; Any/30

55/15; Any/25

Delaware

Delaware State Employees' Pension Plan

Hired on or after Jan. 1, 2012

65/10; 60/20; Any/30

55/15; Any/25

District of Columbia

District of Columbia Teachers' Retirement Plan

Hired before Nov. 1, 1996

62/5; 60/20; 55/30

District of Columbia

District of Columbia Teachers' Retirement Plan

Hired on or after Nov. 1, 1996

62/5; 60/20; Any/30

Florida

Florida Retirement System Pension Plan: Regular Class

Hired before July 1, 2011

62/6; Any/30

42/6

Florida

Florida Retirement System Pension Plan: Regular Class

Hired on or after July 1, 2011

65/8; Any/33

45/8

Florida

Florida Retirement System Investment Plan

Effective July 1, 2002

Any/1

N/A

Georgia

Teachers Retirement System of Georgia (TRS)

60/10; Any/30

Any/25

Hawaii

Employees’ Retirement System of the State of Hawaii (ERS) - Contributory Plan for General Employees

Hired before July 1, 1984

55/5

Any/25

Hawaii

Employees’ Retirement System of the State of Hawaii (ERS) - Noncontributory Plan

Hired on or after July 1, 1984 and before July 1, 2006

55/30; 62/10

55/20

Hawaii

Employees’ Retirement System of the State of Hawaii (ERS) - Hybrid Plan

Hired on or after July 1, 2006 and before July 1, 2012

55/30; 62/5

50/20

Hawaii

Employees’ Retirement System of the State of Hawaii (ERS) - Hybrid Plan

Hired on or after July 1, 2012

60/30; 65/10

50/20

Idaho

Public Employee Retirement System of Idaho (PERSI)

65/5; Age + YOS = 90

55/5

Illinois

Teachers' Retirement System of the State of Illinois

Hired before Jan. 1, 2011 (Tier 1)

65/any; 62/5; 60/10; 55/35

55/20

Illinois

Teachers' Retirement System of the State of Illinois

Hired on or after Jan. 1, 2011 (Tier 2)

65/any; 67/10

62/10

Indiana

Indiana State Teachers Retirement Fund

65/10; 60/15; age 55 and age + YOS = 85

50/15

Iowa

Iowa Public Employees Retirement System (IPERS)

Retired before July 1, 2012

62/20; 65/4; 55 and AGE + YOS = 88; 70 and still working for IPERS

55/4

Iowa

Iowa Public Employees Retirement System (IPERS)

Hired after June 30, 2012

62/20; 65/7; 55 and AGE + YOS = 88; 70 and still working for IPERS

55/7

Kansas

Kansas Public Employees Retirement System: School Tier 1

Hired before July 1, 2009

65/1; 62/10; Age + YOS = 85

55/10

Kansas

Kansas Public Employees Retirement System: School Tier 2

Hired on or after July 1, 2009 and before Jan. 1, 2015

65/5; 60/30

55/10

Kansas

Kansas Public Employees Retirement System: School Tier 3 (Cash Balance)

Hired on or after Jan. 1, 2015

65/5; 60/30

55/10

Kentucky

Kentucky Teachers' Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 1983 and before July 1, 2002

60/5; Any/27

55/5

Kentucky

Kentucky Teachers' Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 2002 and before July 1, 2008

60/5; Any/27

55/5

Kentucky

Kentucky Teachers' Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 2008

60/5; Any/27

55/10

Louisiana

Teachers' Retirement System of Louisiana

Hired before July 1, 1999

60/5; Any/20;

Louisiana

Teachers' Retirement System of Louisiana

Hired on or after July 1, 1999 and before Jan. 1, 2011

60/5; 55/25; Any/30

Any/20

Louisiana

Teachers' Retirement System of Louisiana

Hired on or after Jan. 1, 2011

60/5

Any/20

Maine

Maine Public Employees Retirement System: State and Teacher's Retirement Program

Hired before July 1, 1983

60/1

Any/25

Maine

Maine Public Employees Retirement System: State and Teacher's Retirement Program

Hired on or after July 1, 1983 and before Oct. 1, 1989

62/1

Any/25

Maine

Maine Public Employees Retirement System: State and Teacher's Retirement Program

Hired on or after Oct. 1, 1994 and before July 1, 2006

62/1

Any/25

Maine

Maine Public Employees Retirement System: State and Teacher's Retirement Program

Hired on or after July 1, 2006

65/1

Any/25

Maryland

Maryland State Retirement and Pension System: Teachers' Pension System

Hired on or after July 1, 2011

65/10; Age + YOS = 90;

60/15

Maryland

Maryland State Retirement and Pension System: Teachers' Pension System

Hired between Jan. 1, 1980 and July 30, 2011

65/2; 64/3; 63/4; 62/5; any/30

60/15

Massachusetts

Massachusetts Teachers' Retirement System

Hired on or after Jan. 1, 1979 and before Jan. 1, 1984

55/10; Any/20

Massachusetts

Massachusetts Teachers' Retirement System

Hired on or after Jan. 1, 1984 and before July 1, 1996

55/10; Any/20

Massachusetts

Massachusetts Teachers' Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 1996 and before July 1, 2001

55/10; Any/20

Massachusetts

Massachusetts Teachers' Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 2001 and before April 1, 2012

55/10; Any/20

Massachusetts

Massachusetts Teachers' Retirement System

Hired on or after April 1, 2012

60/10

Michigan

Public School Employees' Retirement System - Basic

Hired before January 1, 1990 and retired before February 1, 2013

55/30; 60/10

55/15

Michigan

Public School Employees' Retirement System - Member Investment Plan (MIP) Fixed - Option 1

Hired before January 1, 1990, elected MIP plan - 25 YOS on February 1, 2013 (Option 1)

Any/30; 60/5; 60/10

55/15

Michigan

Public School Employees' Retirement System - Member Investment Plan (MIP) Fixed - Option 2

Hired before January 1, 1990, elected MIP plan - 25 YOS on February 1, 2013 (Option 2)

Any/30; 60/5; 60/10

55/15

Michigan

Public School Employees' Retirement System - Member Investment Plan (MIP) Fixed - Option 3

Hired before January 1, 1990, elected MIP plan - 25 YOS on February 1, 2013 (Option 3)

Any/30; 60/5; 60/10

55/15

Michigan

Public School Employees' Retirement System - Member Investment Plan (MIP) Fixed - Option 4

Hired before January 1, 1990, elected MIP plan - 25 YOS on February 1, 2013 (Option 4)

Any/30; 60/5; 60/10

55/15

Michigan

Public School Employees' Retirement System - Member Investment Plan (MIP) Graded - Option 1

Hired after December 31, 1989 and before July 1, 2008 - 20 YOS on February 1, 2013 (Option 1)

Any/30; 60/5; 60/10

55/15

Michigan

Public School Employees' Retirement System - Member Investment Plan (MIP) Graded - Option 2

Hired after December 31, 1989 and before July 1, 2008 - 20 YOS on February 1, 2013 (Option 2)

Any/30; 60/5; 60/10

55/15

Michigan

Public School Employees' Retirement System - Member Investment Plan (MIP) Graded - Option 3

Hired after December 31, 1989 and before July 1, 2008 - 20 YOS on February 1, 2013 (Option 3)

Any/30; 60/5; 60/10

55/15

Michigan

Public School Employees' Retirement System - Member Investment Plan (MIP) Graded - Option 4

Hired after December 31, 1989 and before July 1, 2008 - 20 YOS on February 1, 2013 (Option 4)

Any/30; 60/5; 60/10

55/15

Michigan

Public School Employees' Retirement System - Member Investment Plan (MIP) Plus

Hired after June 30, 2008 and before July 1, 2010 (MIP Plus)

Any/30; 60/5; 60/10

55/15

Michigan

Public School Employees' Retirement System - Pension Plus Plan (PPP)

Hired after June 30, 2010 (Pension Plus Plan)

60/10

55/15

Minnesota

Minnesota Teachers Retirement Association

Hired on or before June 30, 1989

65/3; 62/30; Age + YOS = 90

55/3; Any/30

Minnesota

Minnesota Teachers Retirement Association

Hired after June 30, 1989

66/3

55/3

Mississippi

Mississippi Public Employees' Retirement System

Hired before July 1, 2007

60/4; any/25

Mississippi

Mississippi Public Employees' Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 2007 but before July 1, 2011

60/8; any/25

Mississippi

Mississippi Public Employees' Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 2011

65/8; any/30

60/8

Missouri

Public School Retirement System of Missouri

Retire on or before July 1, 2013

60/5; any/30; Age + YOS = 80

55/5; any/25

Missouri

Public School Retirement System of Missouri

Retire after July 1, 2013

60/5; any/30; Age + YOS = 80

55/5; any/25

Montana

Montana Teacher's Retirement System (TRS)

60/5; Any/25

50/5

Nebraska

Nebraska School Employees' Retirement System

65/1; age 55 and age + YOS = 85

60/5

Nevada

Nevada Public Employees' Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 2001 and before Jan. 1, 2010

65/5; 60/10; Any/30

Any/5

Nevada

Nevada Public Employees' Retirement System

Hired on or after Jan. 1, 2010

65/5; 62/10; Any/30

Any/5

New Hampshire

New Hampshire Retirement System

Hired before Jan. 1, 2002

60/1

50/10; 20 YOS and Age + YOS = 70

New Hampshire

New Hampshire Retirement System

Hired on or after Jan. 1, 2002 and before July 1, 2009

60/1

50/10; 20 YOS and Age + YOS = 70

New Hampshire

New Hampshire Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 2009 and before July 1, 2011

60/1

50/10; 20 YOS and Age + YOS = 70

New Hampshire

New Hampshire Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 2011

65/1

60/30

New Jersey

New Jersey Teachers' Pension and Annuity Fund

Hired before July 1, 2007 (Tier 1)

60/10; 55/25

Any/25

New Jersey

New Jersey Teachers' Pension and Annuity Fund

Hired on or after July 1, 2007 and before Nov. 2, 2008 (Tier 2)

60/10

Any/25

New Jersey

New Jersey Teachers' Pension and Annuity Fund

Hired on or after Nov. 2, 2008 and before May 22, 2010 (Tier 3)

62/10

Any/25

New Jersey

New Jersey Teachers' Pension and Annuity Fund

Hired on or after May 22, 2010 and before June 28, 2011 (Tier 4)

62/10

Any/25

New Jersey

New Jersey Teachers' Pension and Annuity Fund

Hired on or after June 28, 2011 (Tier 5)

65/10

Any/30

New Mexico

New Mexico Educational Retirement Board

Hired before July 1, 2010

65/5; Any/25; Age 60 and age + YOS = 75

Age + YOS = 75

New Mexico

New Mexico Educational Retirement Board

Hired on or after July 1, 2010 and before July 1 , 2013

67/5; Any/30; Age 65 and Age + YOS = 80

Age + YOS = 80

New Mexico

New Mexico Educational Retirement Board

Hired on or after July 1 , 2013

67/5; 55/30; Age 65 and Age + YOS = 80

Any/30; Age + YOS = 80

New York

New York State Teachers' Retirement System

Hired on or after July 27, 1976 and before Jan. 1, 2010 (Tiers 3 & 4)

62/5; any/30

55/5

New York

New York State Teachers' Retirement System

Hired on or after Jan. 1, 2010 and before April 1, 2012 (Tier 5)

62/10; 57/30

55/10

New York

New York State Teachers' Retirement System

Hired on or after April 1, 2012 (Tier 6)

63/10

55/10

North Carolina

Teachers' and State Employees' Retirement System (TSERS)

Hired before August 1, 2011

65/5; 60/25; Any/30

50/20; 60/5

North Carolina

Teachers' and State Employees' Retirement System (TSERS)

Hired after July 31, 2011

65/10; 60/25; Any/30

50/20; 60/10

North Dakota

North Dakota Teachers' Fund for Retirement

Hired before July 1, 2008 and age 55 by July 1, 2013

65/3; Age + YOS = 85

55/3

North Dakota

North Dakota Teachers' Fund for Retirement

Hired before July 1, 2008 and younger than 55 on July 1, 2013

65/3; Age 60 and Age + YOS = 90

55/3

North Dakota

North Dakota Teachers' Fund for Retirement

Hired on or after July 1, 2008 and retire after July 1, 2013

65/5; Age 60 and Age + YOS = 90

55/5

Ohio

State Teachers Retirement System of Ohio

Retiring before Aug. 1, 2015

65/5; Any/30

55/25; 60/5

Ohio

State Teachers Retirement System of Ohio

Retiring on or after Aug. 1, 2015 and before Aug. 1, 2017

65/5; Any/31

55/26; 60/5; Any/30

Ohio

State Teachers Retirement System of Ohio

Retiring on or after Aug. 1, 2019 and before Aug. 1, 2021

65/5; Any/33

55/28; 60/5; Any/30

Ohio

State Teachers Retirement System of Ohio

Retiring on or after Aug. 1, 2026

65/5; 60/35

60/5; Any/30

Oklahoma

Oklahoma Teachers Retirement System (TRS) - Low Base

Hired after June 30, 1979 and before July 1, 1992

62/5; AGE + YOS = 80

55/5; Any/30 YOS

Oklahoma

Oklahoma Teachers Retirement System (TRS) - High Base

Hired after June 30, 1979 and before July 1, 1992

62/5; AGE + YOS = 80

55/5; Any/30 YOS

Oklahoma

Oklahoma Teachers Retirement System (TRS) - Low Base

Hired after June 30, 1992 and before July 1, 1995

62/5; AGE + YOS = 90

55/5; Any/30 YOS

Oklahoma

Oklahoma Teachers Retirement System (TRS) - High Base

Hired after June 30, 1992 and before July 1, 1995

62/5; AGE + YOS = 90

55/5; Any/30 YOS

Oklahoma

Oklahoma Teachers Retirement System (TRS) - Low Base

Hired after June 30, 1995 and before November 1, 2011

62/5; AGE + YOS = 90

55/5; Any/30 YOS

Oklahoma

Oklahoma Teachers Retirement System (TRS) - Low Base

Hired on or after November 1, 2011

65/5; 60 and AGE + YOS = 90

60/5; Any/30 YOS

Oregon

Oregon Public Employees Retirement System: Tier One

Hired before July 14, 1995

58/5; any/30

55/5

Oregon

Oregon Public Employees Retirement System: Tier Two

Hired on or after Jan. 1, 1996 and before Aug. 29, 2003

60/5; any/30

55/5

Oregon

Oregon Public Employees Retirement System: OPSRP

Hired on or after Aug. 28, 2003

65/5; 58/30

55/5

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania Public School Employees' Retirement System (PSERS) - Class T-C

Hired before July 1, 2001

62/1; 60/30; Any/35

Any/5; 55/25

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania Public School Employees' Retirement System (PSERS) - Class T-D

Hired after June 30, 2001 and before July 1, 2011

62/1; 60/30; Any/35

Any/5; 55/25

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania Public School Employees' Retirement System (PSERS) - Class T-E

Hired on or after July 1, 2011, Class T-E

65/3; 35 YOS and AGE + YOS = 92

Any/10; 55/25

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania Public School Employees' Retirement System (PSERS) - Class T-F (Optional)

Hired on or after July 1, 2011, Class T-F

65/3; 35 YOS and AGE + YOS = 92

Any/10; 55/25

Rhode Island

Employees' Retirement System of Rhode Island (ERSRI) - Schedule B2

Hired after September 30, 2009 and before July 1, 2012

65/10; 62/29

62/20

Rhode Island

Employees' Retirement System of Rhode Island (ERSRI) - Schedule AB

20 YOS on July 1, 2012

60/10

55/20

Rhode Island

Employees' Retirement System of Rhode Island (ERSRI)

Hired after June 30, 2012

Social Security FRA

Social Security FRA-5/20

South Carolina

South Carolina Retirement System

Hired before July 1, 2012 (Class 2)

65/5; Any/28

60/5; 55/25

South Carolina

South Carolina Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 2012 (Class 3)

65/8; 8 YOS and Age + YOS = 90

60/8

South Dakota

South Dakota Retirement System (Class A)

Retired before July 1, 2008

65/3; Age 55 and Age + YOS = 85

55/3

South Dakota

South Dakota Retirement System (Class A)

Hired on or after July 1, 2008

65/3; Age 55 and Age + YOS = 85

55/3

Tennessee

Tennessee Consolidated Retirement System

Hired on or after July 1, 1976

60/5; any/30

55/5; any/25

Texas

Teacher Retirement System of Texas

Tier 1: hired on or before Sept. 1, 1980, or hired on or before Sept. 1, 2005 and at least age 50 at that time or age + YOS = 70 that year

65/5; Any/5 and Age + YOS = 80

55/5; Any/30

Texas

Teacher Retirement System of Texas

Tier 2: hired after Sept. 1, 1980 and on or before Sept. 1, 2007, and not in Tier 1

65/5; Any/5 and Age + YOS = 80

55/5; Any/30

Texas

Teacher Retirement System of Texas

Tier 3: hired after Sept. 1, 2007

65/5; 60/5 and age + YOS = 80

55/5; Any/30; age + YOS = 80

Utah

Tier 1 Contributory

Hired before July 1, 1975

65/4; Any/30

60/20; 62/10

Utah

Tier 1 Contributory

Hired after June 30, 1975 and before July 1, 1986

65/4; Any/30

60/20; 62/10

Utah

Tier 1 Noncontributory

Hired after June 30, 1986 and before July 1, 2011

65/4; Any/30

60/20; 62/10; Any/25

Utah

Tier 2 Public Employees Contributory Retirement System

Hired after June 30, 2011

65/4; Any/35

60/20; 62/10

Vermont

State Teachers' Retirement System of Vermont

Hired before July 1, 1981

60/any; Any/30

55/5

Vermont

State Teachers' Retirement System of Vermont

Hired on or after July 1, 1981 and before July 1, 1985 (or at least age 57 on July 1, 2010)

62/any; Any/30

55/5

Vermont

State Teachers' Retirement System of Vermont

Hired on or after July 1, 1985 (and younger than age 57 on July 1, 2010)

65/any; Age + YOS = 90

55/5

Virginia

Virginia Retirement System (VRS) - Plan 1

Hired before July 1, 2010 and vested on January 1, 2013

65/5; 50/30

55/5; 50/10

Virginia

Virginia Retirement System (VRS) - Plan 2

Hired after June 30, 2010

Social Security FRA/5; AGE + YOS = 90

60/5

Washington

Washington Teachers' Retirement System (TRS) - Plan 2

Hired after September 30, 1977 and before July 1, 1996

65/5

55/20

Washington

Washington Teachers' Retirement System (TRS) - Plan 3

Hired after June 30, 1996 and before May 1, 2013

65/10; 65/5 with 1+ YOS after age 44

55/10

Washington

Washington Teachers' Retirement System (TRS) - Plan 3

Hired on or after May 1, 2013

65/10; 65/5 with 1+ YOS after age 44

55/10

West Virginia

Teachers' Retirement System (TRS)

55/30; 60/5; Any/35

Any/30-35

Wisconsin

Wisconsin Retirement System (WRS)

Retired before January 1, 2000

65/Any; 57/30

55/Any

Wisconsin

Wisconsin Retirement System (WRS)

20 YOS on January 1, 2000

65/Any; 57/30

55/Any

Wisconsin

Wisconsin Retirement System (WRS)

Hired after June 30, 2011

65/Any; 57/30

55/Any

Wyoming

Wyoming Public Employee Pension Plan

Hired before Sept. 1, 2012

60/4; Age + YOS = 85

50/4; Any/25

Wyoming

Wyoming Public Employee Pension Plan

Hired on or after Sept. 1, 2012

65/4; Age + YOS = 85

55/4; Any/25

Note: Table is based on data from the Urban Institute's State and Local Employee Pension Plan Database.

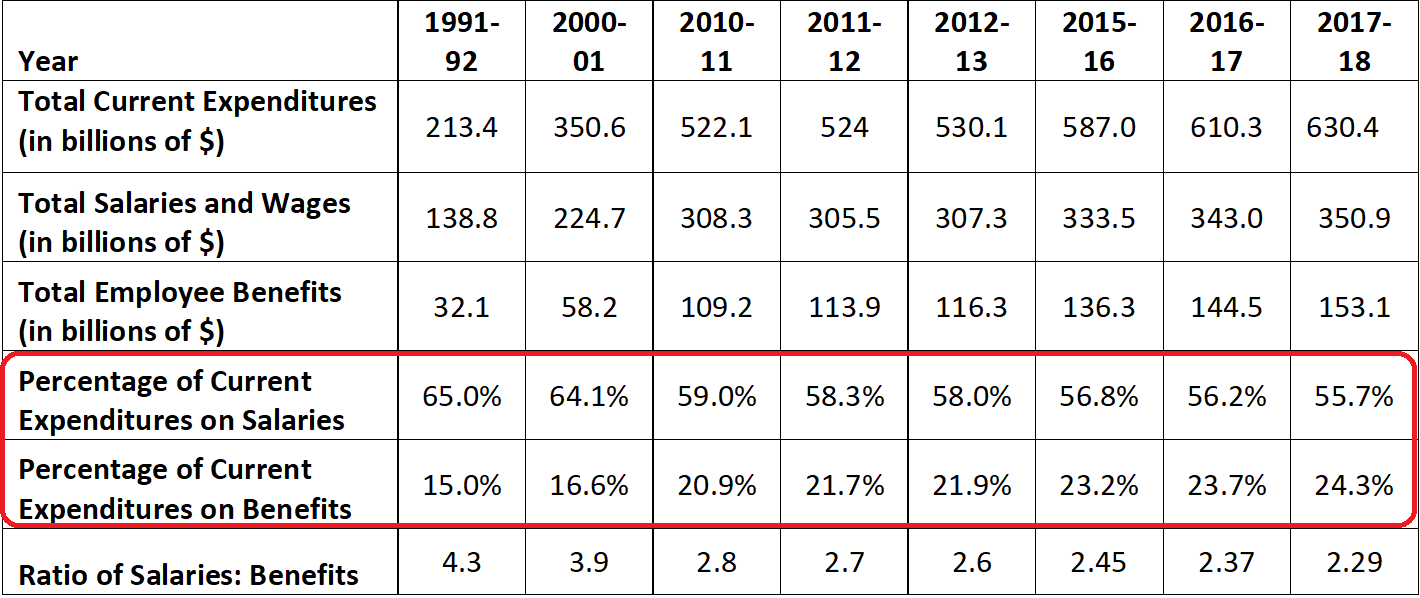

The Census Bureau’s Annual Survey of School System Finances compiles total education spending and revenue across the entire country. The latest data, released earlier this week, shows teacher benefits continue to eat away at school budgets.

In total, public school expenditures have tripled since 1992 (including inflation). The table below shows how those dollars are being spent across broad categories. Figures for all years reflect current expenditures and do not include capital costs or debt.

As the table shows, school districts are spending more and more of their budgets on employee benefits, at the expense of base salaries and wages. Over the long term, the percentage of education budgets going toward salaries fell from 65.0 percent in the 1991-92 school year to 55.7 percent in 2017-18. Over the same time period, the percentage of school district budgets going toward employee benefits increased from 15.0 to 24.3 percent.

As a share of total expenditures, benefits now eat up nine percentage points more than they did in 1992.

These are steady, long-term trends, but they're no less troubling. Increased spending on benefits is one reason teacher salaries have been flat, in real terms, over the last few decades. Benefits are also a less efficient use of money than salaries, since teachers value $1 in take-home pay more than they do $1 in benefit spending. Worse, much of these rising benefit costs reflect the growing burden of debt costs, not actual benefit enhancements for teachers and retirees.

Updated on May 18, 2020

Taxonomy:A Massachusetts teacher emails us with a question about her options for an early retirement:

I am a teacher in Massachusetts. With my last child going to college next year, we have kicked around the idea of moving out of state. This would be after my 15th year of teaching and I will be 51 years old. I see that I am vested after 10 years so my question is:

Could I retire after next school year (my 15th year at age 51) but defer my payment until I am 55 or 60? This would give me 15 years at 55 which I believe would be a reduced pension, or 15 years at 60, which would be a full pension.

I wanted to see if these plans were an option that would be available to me after my 15th year of teaching.

Any information you could provide would be greatly appreciated.

--Massachusetts Teacher

Hi Massachusetts Teacher,

The short answer is yes, you could certainly take either of those options. As long as you don't withdraw your contributions from the Massachusetts Teachers' Retirement Systems, you'd be eligible to begin collecting a pension at either the early or normal retirement ages. Those ages depend on when you started teaching in Massachusetts, see here to determine which tier you are in.

Massashusetts provides a retirement "percentage chart" to help you make your decision. With 15 years of service, if you begin collecting your pension at age 55, you'd be eligible for 22.5 percent of your final average salary. If you wait to collect until age 60, you'd be eligible for a pension equivalent to 30 percent of your final salary.

There are two things to be aware of. One is that your pension will eventually be based on your salary in the last years in which you were employed. That is, your pension amount will essentially be frozen from now until you begin collecting; it won't increase due to inflation.

The second thing is that starting over in a new state would mean significantly less in terms of pension wealth than sticking it out in Massachusetts. Two smaller pensions are usually worth much less than one larger one. This article gives a good explanation of how that works, with a Massachusetts example.

I hope you don't let those cautions discourage you from pursuing your plans to spend time with your family, but hopefully they're helpful as you weigh your options. Best,

~Chad Aldeman

Note: This is a real question submitted to us. We have removed all personally identifiable information, but we believe there's a value in sharing frequently asked questions to benefit others with similar concerns. If you have a question you would like answers to, please feel free to email us at teacherpensions@bellwethereducation.org. Please note that by submitting a question to us, you agree to let us share the question and our answer publicly here on the TeacherPensions.org blog.

Taxonomy:At the same time as states face budget shortfalls in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, public pension plans also lost an estimated $400 billion in assets in the first three months of 2020. In response, as part of a larger request for a COVID-19 relief package the Illinois Senate President called for $10 billion in federal funding to help plug Illinois' state and municipal pension funding gaps.

Historically, Congress has enacted rules and regulations to govern private-sector retirement plans, but it has mostly shied away from extending those rules to the public sector. Should that change? Are state and local pension plans in such a dire situation that they need the federal government's support? And if so, what should Congress ask for in return? We reached out a range of voices to weigh in on these questions. Here are their responses:

Andrew Biggs, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute

Public sector pensions have long argued that they need not abide by the stricter federal funding rules applied to private sector pensions. Private pensions must assume conservative rates of return on investments and must address unfunded liabilities promptly. Under those rules, the average single-employer private pension today is about 86% funded, assuming a 3.4% “discount rate” applied to plan liabilities. Measured using that same discount rate, the average state and local government pension would be around 38% funded. Simply put, for each dollar of promised future benefits, private sector pensions have set aside nearly twice as much money as state and local plans.

State and local governments have long fought stricter pension funding rules. They assumed average investment returns of 7.3% in 2019 and amortized unfunded liabilities over decades rather than years. They claimed that governments have special powers that make the more-prudent federal regulations unnecessary. These arguments were wrong before and today, with pensions worse-funded than following the Great Recess and Illinois requesting $10 billion in federal aid to stay afloat, they are more clearly mistaken.

Federal law already regulates state government workplaces via minimum wage laws, the Affordable Care Act and other means. There is today compelling evidence that underfunded state and local government pensions should be similarly-regulated. But federal regulation of state and local pensions, by covering them under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), could be made voluntary and come with certain benefits.

Congress could allow state and local pensions to become ERISA-regulated in exchange for providing them with financial aid, such as to cover pension contributions over the next several years. Pension participants would also become employees eligible for Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation benefit insurance should their plan become insolvent in the future. In return, the state or local government would need a credible plan to significantly increase future funding of their pension and address unfunded liabilities promptly, while also paying PBGC insurance premiums. Congress might also include a provision requiring that governments seeking federal pensions assistance enroll their employees in Social Security, if not already covered.

But ERISA regulation provides another option: if a state cannot or does not wish to fund a traditional pension to ERISA standards, it can instead freeze its pension and shift employees to a defined contribution, 401(k)-style plan. Because federal law pre-empts state law, ERISA coverage would free states like Illinois from legal prohibitions on changing future benefit accruals or altering the plan’s structure.

The issue is simple: Federal pension regulations exist for a good reason and those reasons apply to governments as much as to private companies. Those regulations offer employers a choice: either run a traditional pension prudently, using conservative assumptions and prompt addressing of unfunded liabilities, or don’t run one at all.

Chantel Boyens, principal policy associate in the Income and Benefits Policy Center at the Urban Institute

One important role of the federal government in supporting state and local governments as they address ballooning debt is to ensure that any steps taken to address financial shortfalls do not undermine the retirement security of workers broadly, and especially the adequacy of benefits for lower-wage workers. This includes preventing state and local governments from reducing pensions below Social Security levels for workers not covered by the program. Pension plans should not be allowed to continue reducing future benefits for workers not covered by Social Security through loopholes and gaps in the existing regulations.

Like other state and local pension plans, plans offered to workers not covered by Social Security have reduced promised benefits for new hires substantially since the Great Recession. But because these plans are offered to workers not covered by Social Security, they are required by law to provide participants with benefits that are at least equivalent to those provided by Social Security. However, recent analyses by Chad Aldeman and Laura Quinby show that the safe harbor test used to determine whether state and local pension plans meet this threshold is not adequate.

As state and local pension plans consider steps to address funding shortfalls, the federal government has a responsibility to ensure that the retirement safety net provided by Social Security protects all workers. For workers outside of Social Security, that means strengthening the safe harbor rule that governs their non-covered pension plans. For example, the rule should consider protections for workers who change jobs and may move in and out of Social Security coverage. Most plans use backloaded benefit formulas and vesting requirements that favor long-tenured workers.

The risks posed to workers by shortfalls in state and local pension plans also underscores the case for moving to a truly universal Social Security program. Covering all workers would impose transition costs on states. The federal government could consider options to help states manage these transition costs over time or even subsidize a portion of the cost to protect the adequacy of benefits for all workers.

Keith Brainard, research director, on behalf of the National Association of State Retirement Administrators

A careful review of the operations and funding of public pensions, their share of overall state and local budgets, and the steps state and local governments are taking to bring their pension plans into long-term solvency, reveals that on the whole, state and local pensions are weathering the COVID-19 crisis. Public retirement system administrative operations have successfully been moved remotely; payments to retirees continue to be made on time and in full; trillions of dollars in public pension fund assets continued to be managed and invested in the financial markets; and measured changes can be expected to continue to be made to ensure public pensions’ long-term sustainability. Suggestions for federal intervention into public pension plans continue to be resoundingly rebuked.

NASRA opposes efforts to both impose new federal regulations on state retirement systems, and to restrict states’ ability to design plans and manage investments. NASRA testimony before a U.S. Congressional Committee in 2011, remains relevant today. Over the last generation, most public pension plans have moved from financing on a pay-as-you-go basis, to funding based on actuarial methods. State and local pensions’ long-term financing strategy, which takes place over decades, should not be mistakenly juxtaposed against current annual revenues and expenditures of state and local governments. Given the differing plan designs and financial pictures across the country, one-size-fits-all federal intervention is unhelpful.

As national organizations representing state and local governments and elected officials have jointly stated, “Federal regulation is neither needed nor warranted, and public retirement systems do not seek federal financial assistance. State and local governments have and continue to take steps to strengthen their pension reserves and operate under a long-term time horizon.”

Dr. Marguerite Roza, research professor at Georgetown University and director of the Edunomics Lab

First and foremost, any federal action on state and municipal pensions must include an expansion of ERISA – the law that requires private sector pension systems to properly fund their obligations on an annual basis. Those underfunded systems that can’t meet the ERISA terms and needing a bailout would then be subject to the following requirements:

1. Close under-funded pension plans to new salary dollars. Pension systems deep in a hole must first stop digging, in this case by closing the pension fund to new salary obligations. Pensions on existing salary dollars would be protected and continue to earn years of service. Employers could award new raises, but the increments of the raise would be non-pensionable (although could be eligible for other compliant retirement plans). Often it is local employers who award late-career raises (which drive up pension obligations) but states who then must pay the pensions. Edunomics Lab analysis shows that California’s CALSTRS plan would have over $16B less in obligations if such a requirement had been imposed 10 years ago (even after accounting for what would be lower employee contributions).

2. Pay for any bailout with a federal tax on pension payments from systems needing rescue funds. In places like Illinois, leaders pledged to unsustainable pensions, ignored their debts, and paid more in salaries (further driving up pension debt). Leaders in other locales, like neighboring Wisconsin, followed a path of fiscal prudence and paid its debts, even when doing so has meant teachers earn $10K less per year. So, who should own Illinois’ pension tab?

Illinois’ TRS fund needs a bailout, and while Illinois leaders haven’t been able to legally modify the generous pensions it promised, the federal government can tax those payments. The tax could take the form of a flat or progressive rate, collected by the pension fund via a monthly withdrawal from pension checks. Where a retired teacher earns $130,000 per year from the Illinois TRS (and yes, plenty do), the payments could be taxed before they ever reach the retiree. Such a tax would only last as long as the fund needed bailing.

This plan gives states the tools they need to get back on track financially without passing the debt burden to younger generations who neither benefitted from the spending nor had no say in the decisions that got us here.

Taxonomy:In a recent op-ed for The Sacramento Bee, Ted Toppin, the chairman of Californians for Retirement Security, argues that traditional pension plans help “flatten the curve” and are “built to withstand the extremes of economic cycles.”

Unfortunately for Californians, the required contribution rates into two the state pension plans covering teachers, firefighters, and police officers—CalSTRS and CalPERS—have been rising for two decades, and will have to rise again in the wake of the coronavirus.

What will the current market downturn mean for those plans? It’s still too early to know for sure, but in a new piece for The 74, I look back at what happened to CalSTRS in the last recession:

Between declining assets and rising liabilities, CalSTRS went from being 89 percent funded in 2007 to 67 percent funded in 2012. Its unfunded liabilities — the gap between what it had saved and what it owed to current and future retirees — grew from $19 billion to $71 billion.

Rather than seizing the opportunity to consider alternative models, California legislators hunkered down with a number of small changes. Like most states, California made its pension benefits worse by creating a new, less generous tier of pension benefits that applied only to new hires. For those workers only, California raised the retirement age by two years.

The state also increased contribution rates required of teachers themselves, as well as state and district budgets. In legislation passed in 2014, the state scheduled CalSTRS contribution rates to slowly ramp up from a total of 18.3 percent in 2014 to 35.3 percent in 2020-21.

CalPERS has pursued similar changes, but neither plan is prepared for the coming recession. Across both plans, the state had an unfunded liability totaling $246 billion as of last April. That figure is surely much higher today. Just like in the last recession, costs are likely to trickle down to workers and taxpayers through higher contribution rates—not to mention less money available for all other public services.

In short, the California pension plans have not yet flattened their curves. Workers and taxpayers will suffer the consequences.

Taxonomy: