On November 11th, the Supreme Court is scheduled to hear oral arguments in the latest challenge to the Affordable Care Act (ACA). What would the case, known as California v. Texas, mean for teachers?

If the Court votes to uphold the law, and thus overturn the lower court's ruling, nothing would change.

If the Court votes in favor of the lower court's decision, the effect on teachers would depends on the reach of the Court's decison.

At its heart, the case deals with the requirement under the ACA for individuals without health insurance to purchase coverage. In 2012, the Court ruled that the individual mandate was lawful because it was a tax, and Congress has the power to levy taxes. But Congress lowered the tax for the individual mandate to $0 as part of its 2017 tax bill, and Republican attorneys general from 18 states subsequently filed suit to claim that, since there's no longer a tax penalty, the individual mandate is unconstitutional.

The federal government, under the direction of the Trump Administration's Justice Department, is also joining the lawsuit in favor of overturning the individual mandate, but it differs slightly from the Republican attorneys general. Whereas the states would like the Court to deicde that throwing out the individual mandate invalidates the entire law, the Justice Department is asking the Supreme Court to send that issue back to the lower courts to decide. (See this explainer from the Kaiser Family Foundation for a longer explanation of the legal questions.)

Public-school teachers could be most affected in the event that the Court determines that the individual mandate is indeed unconstitutional and invalidates the entire law. In that scenario, federal law would no longer guarantee coverage for people with preexisting health conditions such as diabetes, heart conditions, asthma, or, potentially, people who have had COVID-19. In addition, invalidating the ACA would mean that federal law would no longer require health insurance plans to cover children under age 26, and women would no longer be guaranteed access to birth control with no out-of-pocket expenses. That does not mean that teachers would necessarily lose these benefits and protections--school districts could continue to offer them through their health insurance plans--but the federal guarantees would be gone.

In a less extreme outcome, the Court could rule the individual mandate unconstitutional but allow the remainder of the law to stand. In that case, experts predict the individual health insurance market would be destabilized, driving up prices for individuals who must shop for their own plans and leading many more Americans to be uninsured. That may not directly affect workers who receive health insurance benefits through their employers, including 99 percent of public school teachers, but there are still many employees who work in schools who do not receive health insurance benefits from districts. Those employees, including some teaching assistants, substitute teachers, teacher's aides, food service workers, janitors, and bus drivers, could all face a much harder time of remaining insured.

Finally, there's the issue of job lock. In general, older, veteran teachers have very low turnover rates--that is, right up until they become eligible for retiree health care and pension benefits. At that point, they become much more likely to retire. In other words, teachers seem to be aware of and react to their health insurance coverage. In Illinois, for instance, one study prior to the passage of the ACA found that teachers who are eligible for the state's retiree health benefit retire two years earlier than they otherwise would without it. The ACA made that decision less fraught by making it easier for individuals, even ones who might have preexisting conditions, to purchase health insurance on the private market. And, with the ACA's subsidies for individuals earning up to 400 percent of the federal poverty level--that's $69,000 for a household of two--the ACA also protected individuals who did not otherwise qualify for retiree health benefits at all.

In fact, Republicans might rue the loss of the ACA for this exact purpose. As I've argued before, it would make sense for states to offload some of the responsibility for providing retiree health coverage onto the ACA exchanges. Right now, states have amassed $700 billion in unfunded liabilities related to their promises to pay for health benefits for retired public-sector workers like teachers. But states have hardly put aside any money to pay for those promises. So far they've mainly pursued cost-cutting strategies like limiting eligibility to workers who serve for 20 or 25 years, but using the ACA as a release valve could be seen as a win-win all around. States could get rid of their retiree health obligations by relying on the ACA marketplace, and the ACA subsidies would help all lower-income retirees afford coverage. At the same time, such a shift could also create millions of new customers for the individual healthcare plans, which would help stabilize those markets and potentially lower prices for everyone else.

While it may not be obvious why the Supreme Court's decision would affect teachers at all, there are likely ramifications no matter which way the Court decides.

Teacher pension plans are technocratic systems that award benefits through numeric formulas that apply equally to all members. Teacher pension plans are not a racist system; they do not treat people differently based on the color of their skin.

But teacher pension plans are also not anti-racist systems. An anti-racist system would actively fight to push back against broader societal trends and seek to ameliorate racial wealth gaps. If there are any differences across racial lines among their members, teacher pension plan formulas will only amplify and extend those differences into retirement.

Consider how the benefit formulas work. In a typical plan, members earn benefits through a simple formula based on their years of experience and final salary. In the example below, in a state with a 2 percent multiplier, a teacher with 25 years of experience and a final salary of $50,000 would earn an annual benefit of $25,000. Mathematically, it looks this:

On its face, formulas like this are entirely neutral; the formula itself is indifferent to anything else about the teacher.

In the real world, however, teacher pension formulas literally multiply two variables--salary and experience--that are inequitably distributed across students and teachers. Research has found that low-income, Black, and Hispanic students are assigned to teachers with less experience and lower pay than the teachers working with white students. That is, the teachers of Black and Hispanic students receive lower pension benefits than the teachers of white students. The same trends appear among plan members: Black and Hispanic teachers have higher turnover rates and Black teachers at least receive lower pay than their white peers.

Another way to understand how this works is simply to look at the biggest winners and losers under the current system. The biggest winners are long-serving, highly paid workers, especially superintendents and principals, positions that are disproportionately held by white men.The biggest losers under the current systems are lower-paid workers who tend to change jobs more frequently, especially women, teachers of color, and other types of non-teaching staff who happen to be enrolled in so-called "teacher" pension plans.

(Lest anyone wonder if higher-paid workers pay for the more generous benefits they receive, the answer is no. While pension plan contribution rates are a function of salary, and thus higher-paid workers do contribute more while they work, they receive even larger benefits back in return.)

None of these factors make teacher pension plans a racist system per se. And it's fair to acknowledge that any type of retirement plan that delivers benefits as a function of worker salaries will only amplify existing inequities. But teacher pension plans are also not working to address longstanding wealth and income gaps across gender and racial lines that are prevalent in our society.

These problems are not inevitable for retirement plans. Social Security, for example, is a type of defined benefit pension plan that provides proportionately larger benefits to lower-income workers, who are more likely to be Black and Hispanic. States could restructure their benefit formulas to offer better benefits to lower-paid workers. Or, alternatively, states could create retirement plans that award benefits to workers based entirely on their years of service rather than salary. I'm not aware of any teacher pension plan that include progressive features like these, but they could. Without taking such steps, teacher pension plans will continue to turn income gaps among their active members into lifetime wealth gaps for their retirees.

How will teacher retirements change in the midst of COVID-19?

While teacher turnover comes from a variety of causes, retirements typically make up about one-third of all teachers leaving the profession. In this post, I'll look back at what we can say about teacher retirements during a "normal" economic recession and then discuss what's different about the current environment and how that may affect teacher decisions. Based solely on structural factors, we should expect teacher retirements to proceed along normal lines, or perhaps a bit higher than normal.

Teacher Retirements in a "Normal" Recession

About 90 percent of public school teachers are enrolled in defined benefit pension plans, where retirement benefits are guaranteed based on the individual’s years of experience and age. Those plans offer predictable, guaranteed benefit payments regardless of external economic factors. In addition, about two-thirds of public school teachers serve in states or districts that provide health care benefits to eligible retirees.

The combination of guaranteed retirement benefits and health insurance means that public school educators are in a more stable position financially than other Americans who are nearing retirement age. In contrast to teachers, most Americans depend on their own personal savings to fund their retirement and must continue working in order to receive health care benefits from their employer, at least until they turn 65 and qualify for Medicare. While educators or their partners may face other economic hardships, they can at least count on the security of their pension and health care benefits.

Research has found that these structural factors make a difference. Veteran teachers are aware of their pension benefits and time their retirements accordingly. Retiree health care benefits also give teachers confidence to retire at younger ages than they otherwise would.

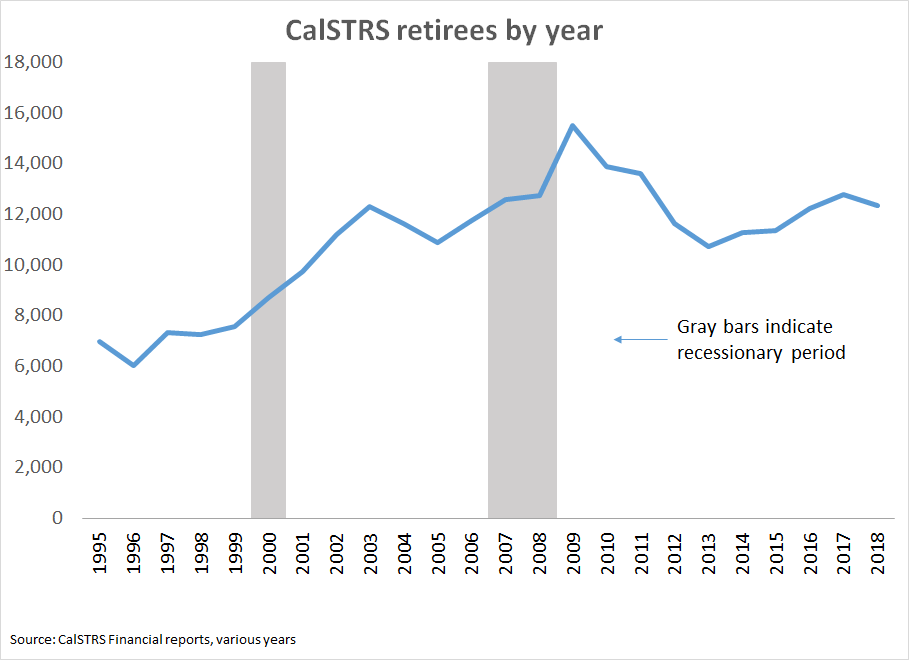

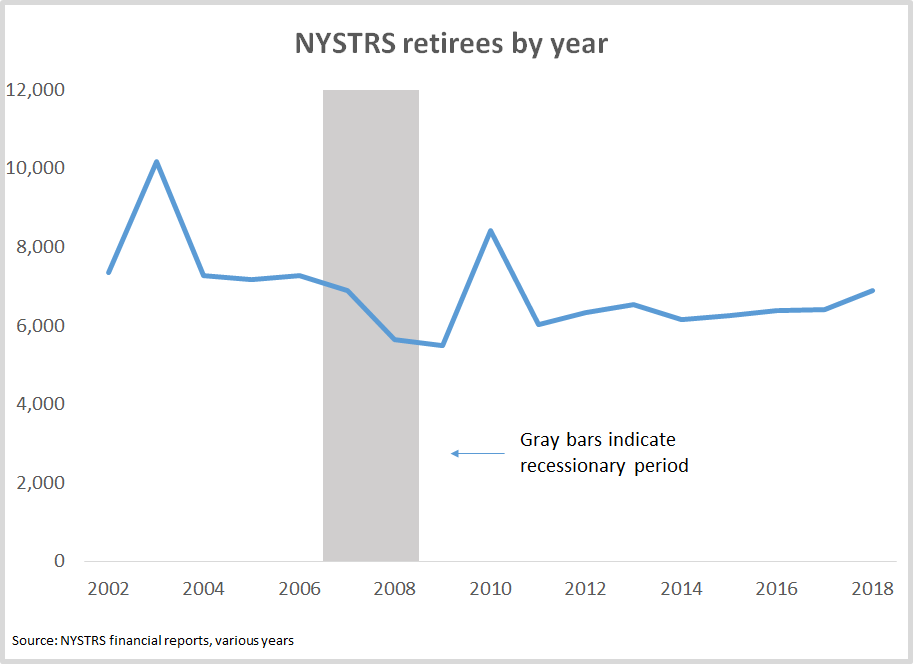

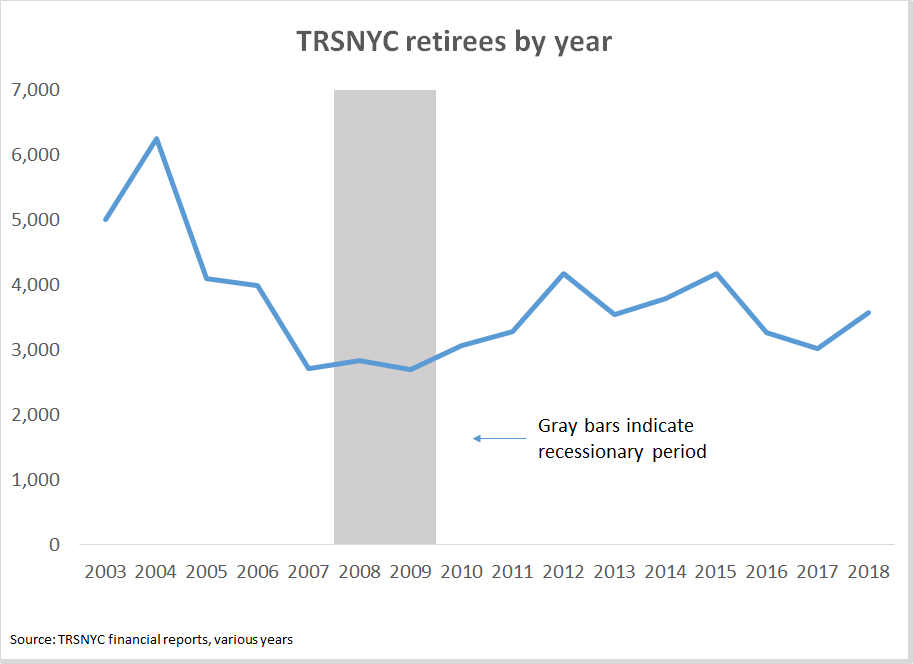

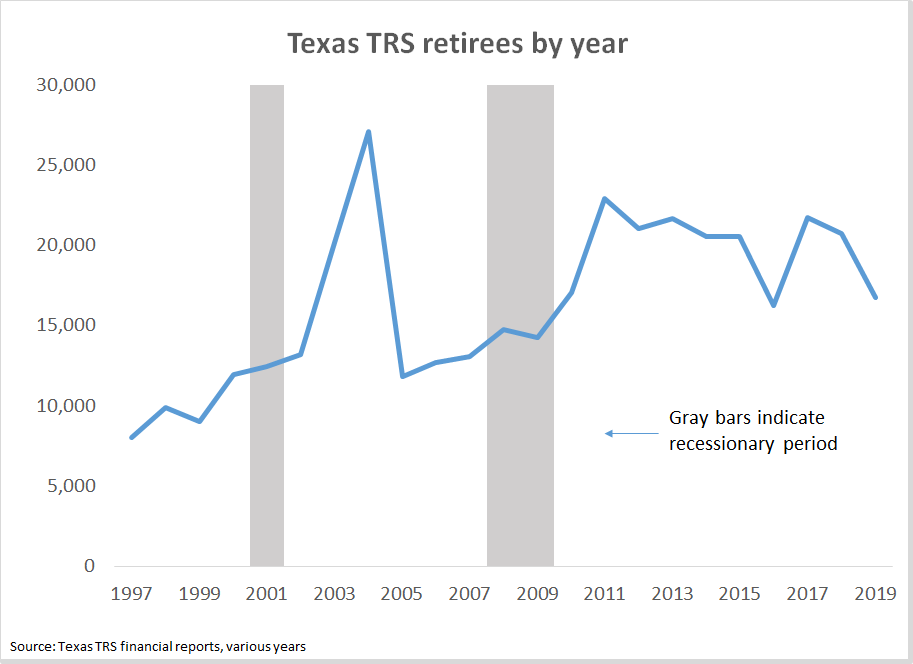

These factors help keep teacher retirements mostly stable year-to-year. To show a few examples, I've pulled data from teacher pension plans in the three states with the most teachers--California, New York, and Texas. The graphs below come from the annual financial reports of the respective teacher pension plans. In each of the graphs, the vertical gray bars indicate official economic recessions, as declared by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Note that, while these plans are named the state's “teacher” pension plan, they also include other education employees.

The first graph shows the number of people retiring from the California State Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS) from 1995-96 to 2018-19. Retirements more or less continued on their prior trajectory during the 2001 and 2007-9 recessions.

The data from New York doesn't go back as far as what I was able to find for California, but it shows similar trends during the Great Recession. The next two graphs show total retirements from the New York State Teachers' Retirement System (NYSTRS) and the Teachers' Retirement System of New York City (TRSNYC). The state system did have fewer retirements during the 2007-9 recession than it had in years prior, but that was part of a downward trend that began in 2003. The spikes in retirements in 2003 and 2011 could reflect some pent-up interest in retirements, but it's hard to know for certain what's causing those.

The data on TRSNYC are even more inconclusive. Like the state as a whole, New York City teacher retirements declined every year from 2004 to 2009 and then rose until 2012.

Finally, the last graph shows retirements by year from the Teacher Retirement System (TRS) of Texas. The data for Texas go back to 1997, which allows us to see both the 2001 and 2007-9 recessions. Again, there's no obvious movement during those recessionary periods, although like New York there does seem to be some pent-up retirements occuring a couple years after the official end of the recessions.

Based solely on economic reasons, we wouldn't expect any dramatic swings in teacher retirement patterns this year, since the current recession only officially began in February. However, our current COVID-19-induced recession is different than a normal economic one. Although we don't have solid data yet, the next section wades through what we might expect.

Teacher Retirements Under COVID-19

Teacher retirement numbers this year are likely to depend on a number of factors, including the spread of COVID-19 cases in the community as well as teacher reactions to school reopening plans.

Nearly a third of traditional public school teachers are aged 50 or older and at heightened risk of the virus. Many of those teachers are close or already eligible for normal or early retirement. (See here for a full list of teacher retirement ages by state.)

In addition to the health risks of the virus, the changing and uncertain nature of what “school” will look like in the coming year may influence teacher retirement decisions. Some teachers may see the transition to distance learning as overly taxing and not what they signed up for, while others could be rededicated to the cause. Austerity measures imposed by schools operating on reduced budgets could also contribute to teacher decisions.

We don't know yet whether teachers nearing retirement age will continue to retire as planned, or if they will become more or less likely to retire as an outgrowth of the pandemic’s economic and health implications. Over the summer, a USA Today/ Ipsos poll found that 18 percent of teachers would leave their jobs if schools were to reopen, including 25 percent of teachers over the age of 55. However, a survey from RAND found that 36 percent of teachers were making their teaching plans based on their eligibility for retirement benefits. In other words, structural issues may continue to play a large role in teacher retirement decisions.

At the margins, some teachers may be more willing to start collecting a pension or file for an early retirement benefit this year, but that theory and the survey results will be put to the test as schools reopen. For now, I think it's safe to predict that teacher retirements will proceed at least in line with recent trends, if not a bit higher. Over the next few weeks, we'll be reaching out to the largest teacher pension plans to see if they can share updated data on teacher retirement figures. Check back soon for those results.

Taxonomy:After lagging behind for much of the decade, average teacher salaries finished with strong gains in the 2019-2020 school year. Based on the new data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, public school teacher salaries rose by 3.2 percent from March 2019 to March 2020, well above the 1.5 percent increase in the consumer price index.

In fact, teacher salaries rose over the entire decade. From 2010 to 2020, average teacher salaries rose by 19.3 percent, slightly above the rate of inflation.

But before celebrating too much, teachers may be miffed to find out that their total compensation increased even more, by 28.5 percent over the same time period. In real terms, teachers got a tiny bit more in their pockets even as employers were paying significantly more money to employ them.

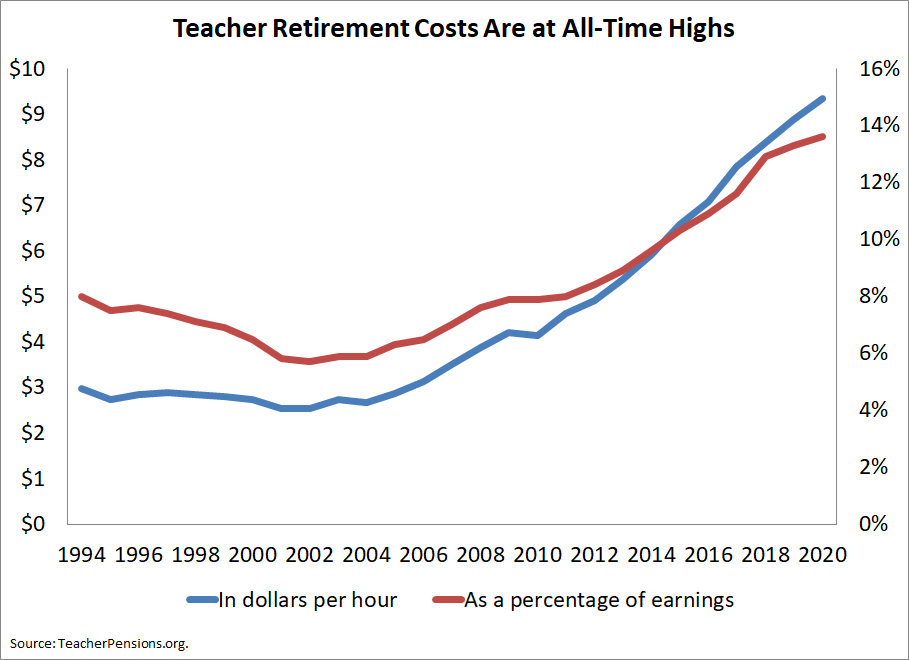

What's driving this disconnect? Benefits costs. Health care and pension payments rose much faster than teacher salaries did and, as a result, benefits are eating up a growing share of teacher compensation. Teacher health care costs rose by 27.6 percent over the course of the decade, well above the rates for wages or inflation, but the real culprit was teacher pensions. Over the last decade, teacher retirement costs soared by 126.4 percent.

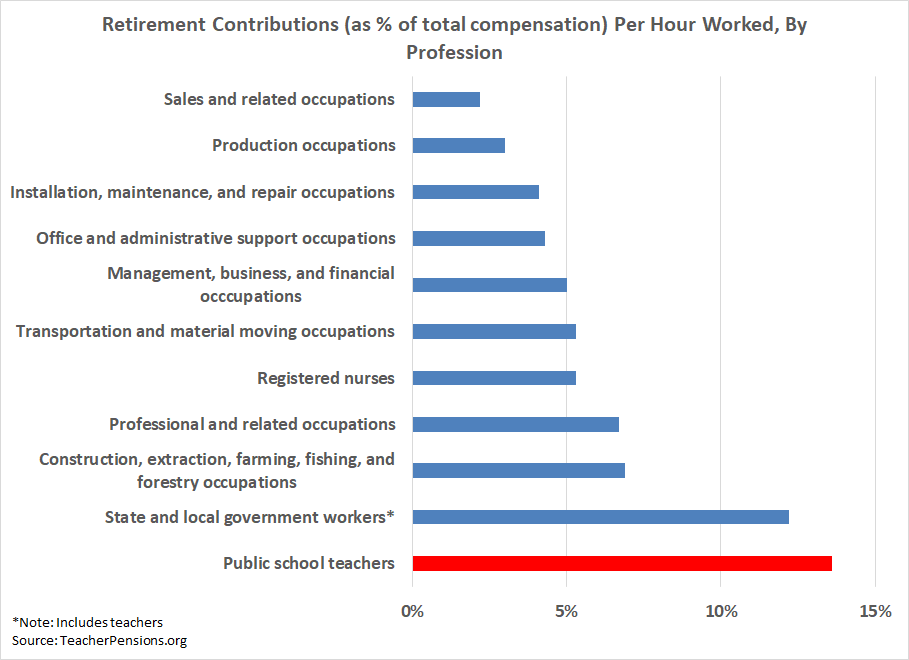

Back in 2016, I dubbed this trend the "Pension Pac-Man" and warned that teachers already had higher retirement costs than any other employee group in the American economy. The trend has only continued since then. While the average civilian employee receives $1.97 in retirement benefits per hour of work, public school districts pay retirement costs of $9.35 per hour. Even if you look at it as a percentage of their total compensation package, teacher retirement benefits eat up two and a half times as much as other workers (13.6 versus 5.2 percent). In terms of retirement costs, teachers are even starting to pull away from other state and local government employees.

Not only are retirement costs for teachers high compared to other professions, they're also high compared to historical trends. Going back to 1994, teacher retirement costs have never been higher, in either dollar or percentage terms. At the end of 1990s, as pension fund assets ballooned in tandem with rising stock prices, teacher retirement costs per hour briefly dipped as a share of teachers’ total compensation package. But beginning in the ealry 2000s, pension funds needed an infusion of new money. That trend has continued to accelerate in recent years as pension costs continue to eat up a higher and higher share of teacher compensation.

Unfortunately for teachers, the rising costs of their retirement systems do not reflect improved benefits. Today, the costs of paying down unfunded liabilities, not benefits for active teachers, make up the biggest proportion of employer retirement costs.

Going forward, it's possible that salaries could continue to rise thanks to recently negotiated teacher contracts. Even in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, some leaders have made good on their promises to find money for teachers salaries. But the Pension Pac-Man continues to eat. And without a change change, retirement costs will continue to eat further and further into school district budgets.

With school districts across the country laying off thousands of teachers and other employees, it might be hard to focus on something as long-term as retirement benefits. But layoffs are particularly harmful to workers covered by teacher pension plans.

Let's use Massachusetts as an example. As Daarel Burnette II and Madeline Will reported in a recent story for Education Week, "the Massachusetts Teachers Association estimates that more than 2,000 teachers and education support professionals in that state have been laid off in about 50 districts."

Although the stories don't all specify whether the laid-off workers were unionized teachers or other types of workers, it's likely that most of the laid-off employees were enrolled in a traditional defined benefit pension plan run by the Massachusetts Teachers' Retirement System (MTRS). MTRS has two tiers of benefits depending on the employee's hire date, and workers hired since 2012 are in Tier 2. Since Tier 2 workers must serve for at least 10 years before qualifying for a pension, the reality is that no Tier 2 member has qualified for a pension yet. They are eligible for 3 percent interest on their own contributions, but they are not eligible for employer-provided retirement benefit.

Worse, Massachusetts teachers are not enrolled in Social Security, so they may be leaving their service with very meager retirement benefits.

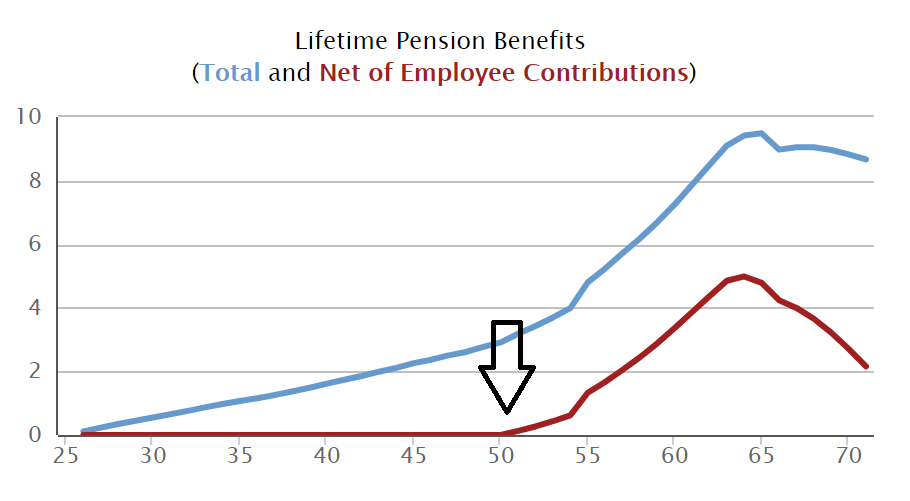

Even for teachers who are vested in MTRS, the benefit formulas are so back-loaded that employees would need to stay for 25 years or more to qualify for a positive benefit. To see this visually, check out the graph below from the Urban Institute's State and Local Employee Pension Plan database. It shows how retirement benefits accumulate under Tier 2 for hypothetical teachers who begin their Massachusetts teaching career at age 25. The blue line tracks their total benefits earned, and the red line shows the benefits earned net of the employee's own contributions. I've added an arrow where the net benefit turns positive, around age 50.

As the graph shows, Tier 2 members won't qualify for a pension worth more than their own contributions until they have served for at least 25 consecutive years. Many of the laid-off Massachusetts school employees are likely to fall short of this mark. In other words, it's likely the case that Massachusetts school districts are laying off workers with no positive retirement benefit, and no Social Security to show for their years of service.

Massachusetts is somewhat of an extreme example, but most states require teachers, especially newer teachers, to serve for 20 or 25 years before qualifying for a pension benefit worth more than their own contributions.

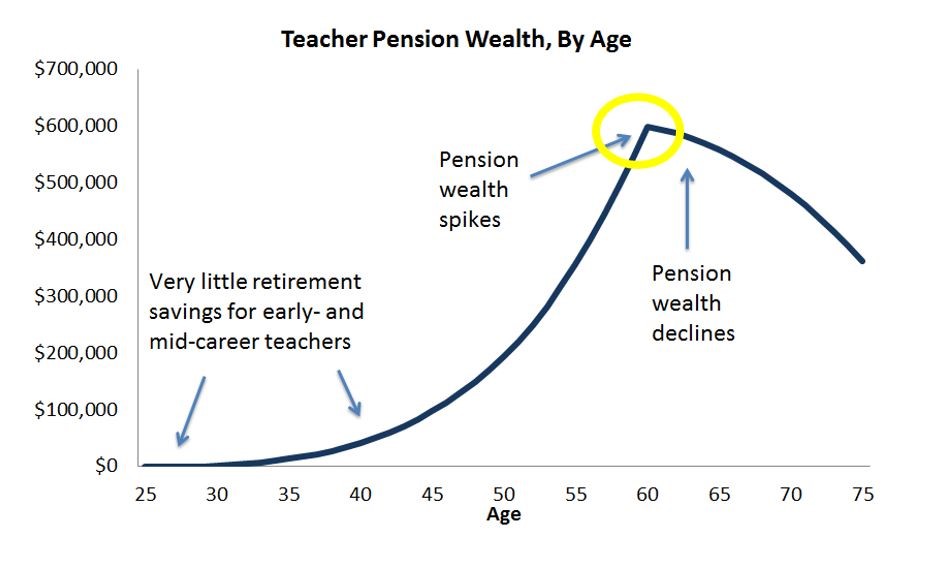

Although the decision about when to retire is a personal one involving many factors, in most states there is a very clear window during which you can maximize your retirement wealth. As explained below, you can receive the most total money in pension benefits by following two rules: stay in the same pension plan for as many years as possible, and then retire at your state’s normal retirement age.

In the 401(k)-style plans common in the private sector, your pension wealth is tied directly to your contributions, the contributions of your employer, and the investment returns earned by these contributions. In most states, however, public school teachers receive a Defined Benefit (DB) retirement plan. In these plans, pension wealth is instead tied to a formula that calculates a monthly defined benefit based on years of service in that retirement system and final average salary (usually calculated as your average salary over the three to five highest-earning years of your career in the system). These two numbers are then multiplied together, and a small percentage of that factor — usually around 2% — becomes your monthly defined benefit.

These pension rules offer some clear guidelines about how to maximize your pension wealth. First, you should work as long as you can in one system. Because your defined benefit is calculated based on years of service in a system, switching systems will most likely leave you with two small benefits that, when combined, are less than the one large benefit you would have gotten if you had remained in one plan for your entire career.

In addition, you should think twice about retiring earlier than the normal retirement age. In California, for example, the normal retirement age is 62, meaning that a teacher who retires at that age receives a benefit based on the 2% formula multiplier. However, if you retire at the age of 55 — the earliest possible retirement age — the state will instead use a multiplier of 1.16% to calculate your pension benefit.

Financially, it also makes sense to avoid retiring much later than the normal retirement age. You get your pension benefit in the form of yearly payments rather than as a lump sum of cash. This means that as you age, even if you receive a higher amount of money per year, you will have fewer years of life to receive these payments.

For example, imagine that you can either retire now and earn an annual retirement benefit of $50,000, or retire in five years and receive a retirement benefit of $60,000. By waiting five years to retire, you would lose more than $250,000 in pension wealth, then earn an additional $10,000 every year after that (not including inflation). This means that you would have to live 25 years past that later retirement date in order to receive the same amount of money as you would have if you had retired at your state’s normal retirement age. Therefore, you should keep in mind your health at your time of retirement and decide whether the slightly higher pension payments are worth the loss of years of annual payments. (This advice is merely about maximizing one’s pension wealth and does not consider a teacher’s desire to continue teaching.)

All of these factors combined create a structure in which pension wealth remains low throughout most of a teacher’s career, spikes at the state’s normal retirement age, then slowly declines from there. So an ideal window to retire begins at your state’s normal retirement age and continues for a few years after that. A typical plan provides a trajectory of pension wealth that looks something like the graph below:

With an understanding of this pension structure in mind, you should be able to make an informed decision about what retirement age is best for you and your family. For more information about your state’s pension plan, check out our state teacher pension plans page here, or look at your state pension plan’s member guide that can be found at your plan’s website. And for more information about how to calculate a teacher pension, read our explainer post here.

Taxonomy: