Across the United States, growing unfunded pension liabilities have quietly slashed state education budgets, leaving fewer dollars for teacher salaries, classroom resources and other education priorities. A new report from Equable Institute has found the share of state education spending going to pension costs has nearly doubled from 7.5% in 2001 to 14.4% in 2018. The report is the first of its kind to quantify the effects of growing unfunded liabilities on the education system in detail.

Hidden Education Funding Cuts provides a state by state analysis of state education funding trends over the past two decades, and then adjusts that spending for inflation and pension costs to show what the ultimate effect has been of growing unfunded pension liabilities on K–12 resources.

Want to find out more about the hidden education cuts in your state? State specific reports and the national summary paper can be downloaded at Equable.org/hiddenfundingcuts.

What are “hidden education funding cuts”?

Since 2001, teacher pension plans have collectively fallen hundreds of billions of dollars behind in the savings levels necessary to pay all future promised benefits. Meanwhile, state K–12 education spending levels have generally been stagnant. Many states simply have not ensured education funding levels are keeping up with the increased costs created by pension funding shortfalls.

In an era when school districts nationwide are struggling financially, growing pension costs are exacerbating already-existing fiscal stress. The result is that less education money is available today for teacher salaries and classroom spending than there would be if teacher pension funds had been better managed over the past two decades. And that’s the hidden cut to education funding.

Where the national trend has seen hidden cuts nearly double from 7.5% to 14.4% of state K–12 funding going to teacher pension costs, the state to state results have varied. In Pennsylvania, exploding teacher pension debt has caused the rate of hidden cuts to surge from 2% to 34% between 2001 and 2018. The absolute hidden cut level has reached a similar 34% in 2018 for Illinois, up from 12%.

The effects of these cuts are felt particularly hard in high-need districts which have fewer local resources to draw on to fill in the gaps when education costs rise, creating less funding for teacher salaries and programs aimed at improving academic and other outcomes.

How did this happen?

Visit Equable’s interactive report website to dig into the details on how education budgets have stagnated while teacher pension costs soared since 2001.

To see how individual states stack up against each other in terms of how much their hidden education funding cuts have changed over the past two decades, see the chart below.

Anthony Randazzo is executive director at Equable Institute, a bipartisan non-profit working to create a safe, more secure retirement for public workers everywhere.

Taxonomy:The economic collapse in the wake of COVID-19 will hurt investment returns, whether those investments are held by individuals in their 401(k) accounts or in public-sector pension plans.

As states grapple with the consequences of a $1 trillion growth in unfunded liabilities, we’re likely to see calls for states to close their defined benefit pension plans and replace them with defined contribution accounts, like 401ks. Pension advocates may respond that the current environment shows exactly why not to take such a move, since the economic collapse presents a stark illustration of what might happen if we shifted all investment risks from state and local governments onto individuals.

But as I write in a new piece for The Omaha World-Herald, there’s another alternative that states should consider. This option, called a “cash balance” plan, should be particularly appealing to teachers. Cash balance plans balance the risks between employees and employers, provide a more portable benefit than traditional pension plans, and help prevent the build-up of unfunded liabilities.

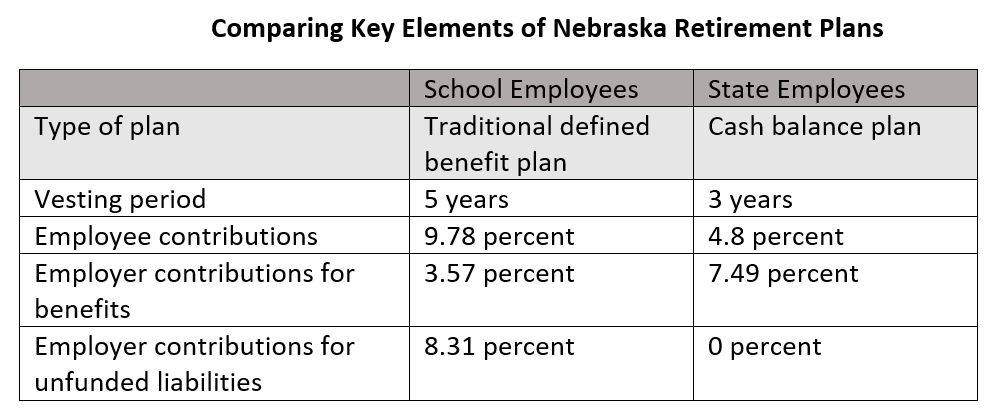

To illustrate this issue, consider the contrast between the retirement benefits Nebraska provides its school employees and its state employees. Teachers and other educators are enrolled in a traditional defined benefit pension system, while state employees hired since 2003 are enrolled in a cash balance plan.

Under Nebraska’s School Employees’ Retirement System, the state has built up an unfunded liability of $1.3 billion. In response, the state has raised contribution rates and introduced new, less generous benefit tiers for workers based on their hire date. Employees must serve for at least five years before qualifying for a pension (called the vesting period). Those hired post-2018 are placed in Tier Four. They must contribute 9.78 percent of their salary and are eligible to retire at age 65 or as early as age 60 if the sum of their age and years of service is more than 85 (called the “rule of 85.”). At that point, they qualify for a pension worth 2 percent times their years of service times the average of their five highest years of salary.

Due to very high early-career turnover rates, only about one-third of new Nebraska educators will qualify for any pension at all, and only about one-in-eight will leave with a pension benefit worth more than their own contributions plus interest.

In contrast, since 2003 Nebraska has enrolled all new state employees in a different type of retirement plan. Commonly known as a cash balance plan, it is legally a defined benefit plan. But rather than conferring benefits via a formula, it guarantees employees a minimum rate of return on their investments. In Nebraska, that figure is 5 percent a year, plus additional interest credits and dividends when investment returns are strong. Employees contribute 4.8 percent of salary, and after vesting at three years, employees receive a state matching contribution equal to 7.49 percent of their salary. Upon reaching retirement age, cash balance plan members can collect a monthly annuity (just like a pension plan) or take their money as a lump-sum.

The table below compares the two plans as of today. Compared to state employees, school employees have to wait longer to collect a retirement benefit (five years versus three), pay higher contribution rates (9.78 versus 4.8 percent), and receive less in employer-provided benefits (3.57 percent of salary versus 7.49 percent). Moreover, employers under the school plan are paying an additional 8.31 percent of each member’s salary to pay down the plan’s unfunded liabilities. That money could be going toward salaries or other school services but is instead being siphoned off to pay for the plan’s pension debts.

The teacher plan already has more than $1 billion in unfunded liabilities. If the past recession is any guide, it will likely need to raise contribution rates again and/ or make further benefit cuts.

In contrast, Nebraska's cash balance plan is currently operating a surplus and has mainted a funding ratio of 90 percent or more every year since it began. In the midst of the current economic downturn, the cash balance plan will continue crediting employees with the same 5 percent investment return guarantee. While those of us with 401k plans will watch our investments decline, and teachers will feel the effects of a downturn via their pension benefits, Nebraska state employees can rest easy knowing their investments will continue to grow at the same 5 percent rate.

Taxonomy:Illinois’ pension contributions have grown to over 20 percent of the state’s available general funds revenues; this limits other critical investments in education, social services and infrastructure, all of which are vital to the state’s growth.

This sentence appears in Illinois' official Fiscal Year 2021 budget book, released just a few weeks ago in late February. It's likely badly out of date already, as the state faces mounting health care costs and falling tax receipts in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak. Meanwhile, the state's pension systems are likely taking a massive hit in the stock markets, which will drive up pensions costs in the years to come.

This is not unique to Illinois, nor will it be new information to many of the state's residents. But it's striking to look at the trajectory over time to see just how much pension costs are strangling public education in the Land of Lincoln.

To get a sense of what that looks like, I collected data from the Public Plans Database on contributions toward public-sector pension plans. In Illinois, almost all of those contributions come out of the state's general fund, rather than being passed along to school districts or other employers. For my purposes here, I used something called "required contribution rates," which reflect the plan's best guess for how much the state needs to contribute in any given year in order to pay out future benefits down the road.

Next, I collected data on the state's direct spending on K-12 and higher education from the National Association of State Budget Officers. To get a sense of the state's spending on current students, I excluded expenditures on bonds and contributions from federal funds.

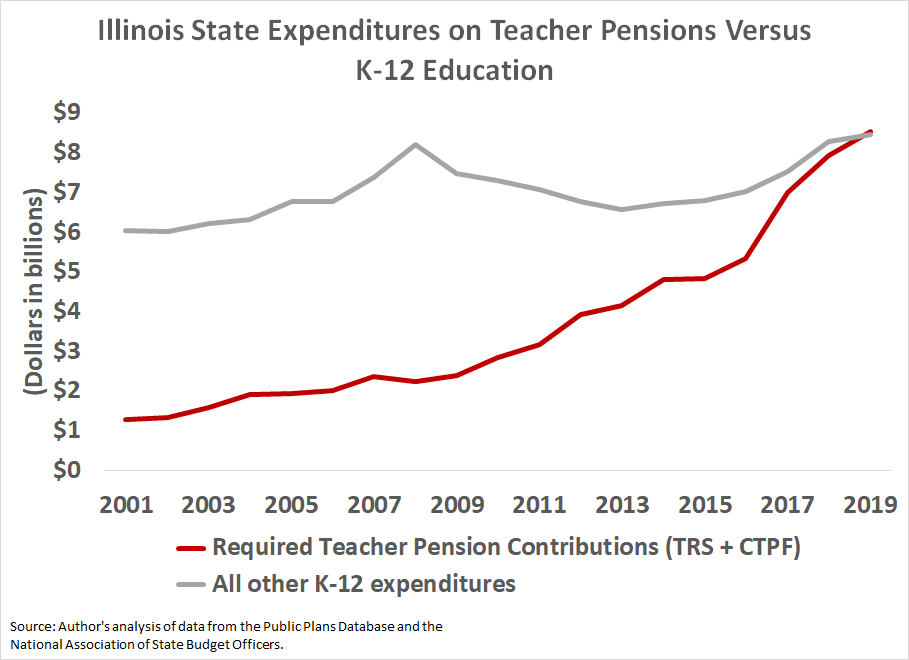

The first graph below shows the results on the K-12 side. As the gray line shows, Illinois' spending on elementary and secondary education has held up reasonably well. From 2001 to 2019, Illinois increased its K-12 expenditures by about $2.4 billion. Although this reflects the raw, unadjusted figure, Illinois' K-12 spending has also held up even on a real, per-pupil basis.

However, Illinois' required teacher pension contributions (represented by the red line in the graph) have increased much faster. Between the statewide Teachers' Retirement System (TRS) and the Chicago Teachers' Pension Fund (CTPF), the required teacher pension contributions have risen by $7.2 billion over the same time period. In fact, in 2019 Illinois' required teacher pension contributions surpassed what the state allocated for all other K-12 expenditures.

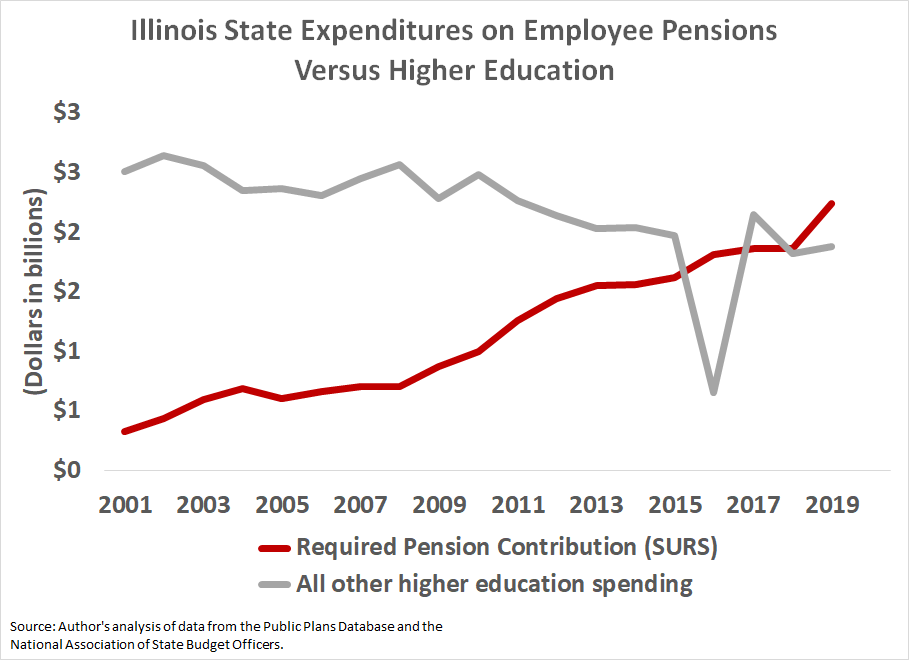

The story is similar for higher education, except that Illinois has not been able to protect its colleges and universities from budget cuts. Again, this isn't just an Illinois story, but states have been asking their public higher education institutions to do more with less, or else raise student tuition and fees to make up the difference. As in the first chart, the gray line in the next graph shows Illinois' declining support for public higher education.

The red line again represents required pension contributions, this time toward the State University Retirement System (SURS). Required pension contributions first surpassed the state's higher education spending in 2016, during a particularly bad budget year. The state's higher education budget has improved slightly since then, but the required contributions into SURS were again higher than what the state spent on all of its colleges and universities in both 2018 and 2019.

In raw dollar amounts, Illinois reduced its higher education spending by about $630 million over the last two decades. Again, that's in nominal dollars and is not adjusted for inflation or changes in student enrollment. Meanwhile, the required pension contributions into SURS rose by $1.9 billion over the same time period.

Of course, Illinois has not actually been making its "required" pension contributions. Over the last two decades, the state has contributed just 77 percent of what actuaries said it needed to pay into SURS, 70 percent of what actuaries estimated TRS needed, and just 56 percent of what CTPF neeeded. That adds up to billions of dollars that should be in the plans today if Illinois policymakers had been more responsible in years past. Those shortfalls have also contributed to the dramatic rise in the required contribution rates.

While it’s hard to pin down causality, this period of rapidly rising pension costs has been associated with benefit cuts for active workers, including both teachers and other public-sector employees. Due to legal protections, Illinois applied those changes only to new workers. In effect, those changes handed a disproportionately large bill to future generations.

Whether we’re talking about the effects on teachers or college students, Illinois and other states with high pension costs are punishing future generations to pay for the mistakes of the past.

Taxonomy:Today is Equal Pay Day -- our annual reminder that women do not receive equal pay for equal work. Although most educators are women, education nevertheless struggles with gender-based salary inequities. Pay gaps persist even though most school districts use a fixed salary schedule based on years of experience and educational attainment. Among teachers, principals, and superintendents, researchers have documented gender wage gaps. In 2018, I analyzed Illinois teacher salary data and found that across the state female teachers earn on average 92 percent of what male teachers earn. Race further complicates the problem. For example, Hispanic women earned about $4,000 less than Hispanic men, and white women earned $10,000 less than white men.

A new study by Grissom et al., out of the Annenberg Institute at Brown University found similar patterns of pay inequities among principals. Using educator-level records, the researchers found that school principals in Missouri earn around $1,400 less per year than their male colleagues. And using the nationally representative Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS), they found that across the country female school leaders earn $900 less than male ones. Gender-based salary gaps can only be “partially explained” by career path choices, suggesting gender discrimination contributes to male-female pay differences in school leadership.”

If you take into consideration an educator’s total compensation, including their pensions, the inequities increase considerably. As I wrote previously, any gaps in salary are reflected, and often are amplified through statewide teacher pension systems. As shown in the graph below, women qualify for lower value pensions at every stage in their career.

After 30 years, about the time many educators will be considering retirement, the gender pay gap is about $10,000. If two typical educators, one female and one male, retired after 30 years, the man would receive $8,000 more in pension benefits each year. After 10 years in retirement when they’re both about 70 years old, the male educator will have collected $80,000 more in pension benefits than his female colleague.

It is critical that we better understand the causes and impacts of gender-based pay disparities in schools. However, we must also remember that the salary gap is only part of the disparity in total compensation.

Taxonomy:How will COVID-19 affect teacher pensions? The best way to answer that question is to answer it for specific groups:

Retirees will be mostly unaffected. There may be some states that pause or reconsider their policies around cost-of-living adjustments, but for the most part current retirees can rest assured that their pension checks will continue as before.

Teachers about to retire should also be unaffected. Teachers in this group should double check with their plan, but as long as they remain employed and continue their pension contributions, the current school year should count toward their "years of service" toward their benefits. If that is the case, teachers can continue to make plans just as before, knowing that the pension they were promised will still be intact.

Pension plan administrators will likely remind state politicians and the general public that public-sector pension plans are meant to be long-term investors providing patient capital to the markets. They will prefer to sit tight and weather the storm.

State governors and legislators will be handed a large bill from their pension plan administrators. We don't know yet exactly how large this bill might be, but that money will have to be made up somehow.

School district leaders should be prepared for sharing a portion of the pension bill. Depending on the state, that may come through lower state education spending, higher employer contribution rates, or a combination of both.

Current teachers are typically protected from any changes to their benefits, but they could see a rise in their own contribution rates. This will feel like a cut in take-home pay, and it means they'll be contributing more for the same retirement benefit. On top of that, teachers may also see their district freezing salary schedules, imposing hiring freezes, or cutting other services.

Future teachers will be hit the hardest. They will face the full brunt of any pension contribution rate increases. Plus, if states need to reduce their benefit costs, they often apply any changes only to future employees. That helps protect current workers and retirees, but it means the cuts on new workers must be even larger to achieve the same level of savings.

Washington Post columnist Jay Mathews has a new piece on teacher pensions with a headline that reads, “So you think teacher pensions are too big? Relax. Few ever get them.”

In other words, the truth is somewhere between people who think that teacher pensions are too generous and those who think they’re just fine. Jay lets Bellwether Education Partner co-founder and partner Andrew Rotherham explain:

Rotherham, a former adviser in the Clinton White House and a former member of the Virginia state school board, has long been a leading expert on education policy. He told me more than half of people who teach never get any kind of pension. In 16 states, you have to be teaching for 10 years before you qualify.

“People say we should reward longevity, and I think we should,” he said. “But life happens to people and lots of teachers don’t teach for decades in one place, not because they don’t love teaching, or aren’t good at it, or don’t want to, but because they have to move because of their spouse’s career, military service, a sick relative, whatever.”

Read the full column here.