Giving teachers a say over their retirement plan just might be good for everyone.

The majority of states enroll their public school teachers in defined benefit (DB) pension plans. These plans are back-loaded, and they mainly benefit the small portion of teachers who remain both in the classroom and in the same state for 20 years or more. Supporters of these plans argue pensions are a retention tool – teachers might be less likely to leave the profession if there’s a large financial incentive waiting for them if they stay. These advocates rarely acknowledge that this idea suggests it's ok to use someone's retirement security as a tool to shape their behavior, but it's worth investigating whether these claims play out in pratice. That is, does a teacher's retirement plan shape her behavior?

My colleague Chad Aldeman has a forthcoming piece on this question in Education Next, but a recent study published by the National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER) provides some initial answers. The study, authored by Dan Goldhaber, Cyrus Grout, and Kristian Holden, looked at what happened when Washington State switched from a pure DB system to a hybrid plan. Hybrid plans combine aspects from portable, defined contribution (DC) models, like 401(k)s, as well as traditional, defined benefit plans, like most pensions. Here’s how it worked:

Washington introduced their current hybrid plan (called TRS3) in 1995, to replace their existing DB plan (TRS2). At the time, existing employees remained in the original DB plan, while new hires were enrolled in the new hybrid plan. A two-year transfer period allowed teachers in the DB plan the option to switch into the hybrid plan – those who did so received a bonus payment equal to 65% of their accrued TRS2 contributions.

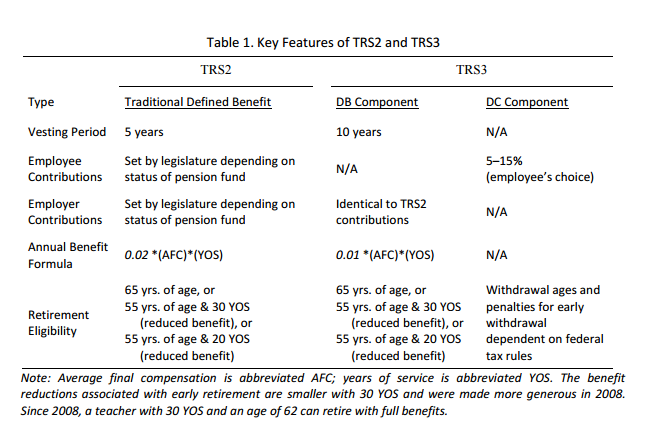

In 2007, Washington made changes again. Teachers hired after that point can select either the DB plan or the hybrid plan, with the latter as the default option for those who do not make an affirmative selection. The table below shows the differences between the two plans:

Public Pension Reform and Teacher Turnover: Evidence from Washington State 2015

So what happened to teacher retention after Washington changed its retirement plan? The study compares three sets of teacher turnover rates:

1. Teachers hired just before and after the introduction of the hybrid plan

2. Teachers who could choose between the DB or hybrid plan as new hires