Last week, Chad Aldeman and I attended the annual Association of Education Finance and Policy (AEFP) conference in Denver where we shared our latest research on inequities inherent in teacher pension plans. Below are descriptions of selected slides from our presentation:

Our work starts with the premise that teacher salaries are often unequal across cities and schools. Wealthier communities will likely offer higher salaries than poorer ones. Wealthier districts may then be able to attract and retain more experienced teachers. Since teachers are distributed inequitably across states and within districts, our hypothesis is that pensions exacerbate these inequities.

Pension benefits are based on a formula consisting of a plan multiplier, the worker's salary, and their years of experience. The formula literally multiplies these factors together. If the factors themselves--salary and experience--are unequal, then the pension benefits will amplify those inequities.

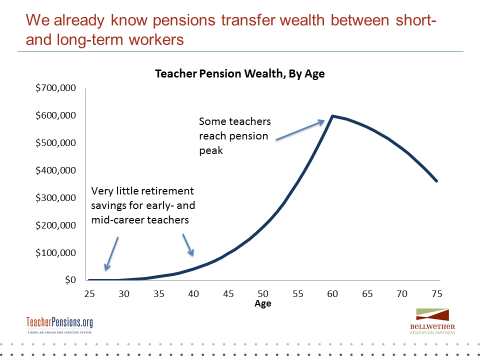

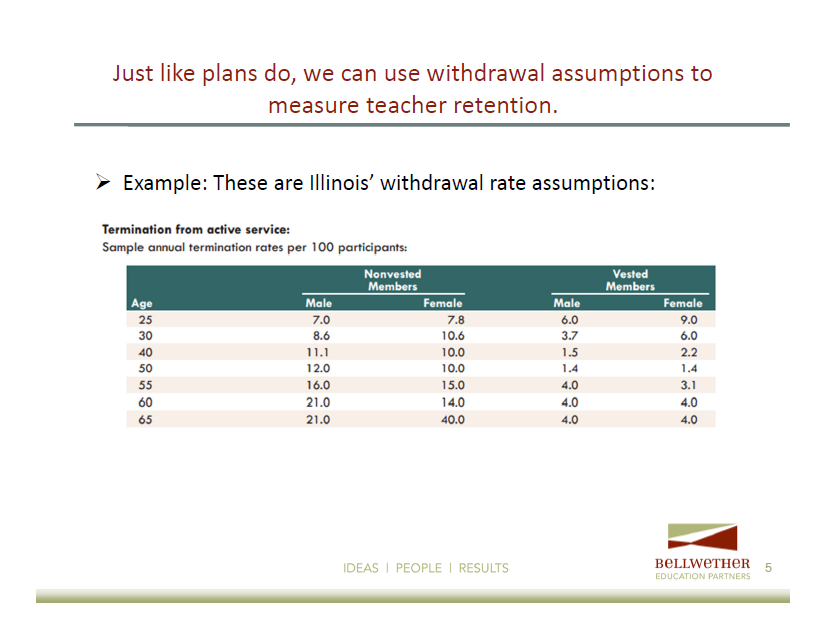

Moreover, we know that pension systems are inequitable in other ways. Traditional pensions accrue wealth unevenly, beginning relatively low during the early years of service and rapidly accruing benefits at the back end after 25 or more years of experience. The majority of teachers will end up with minimal or no benefits, and the system depends upon these teachers to subsidize the benefits of workers with full-career benefits.

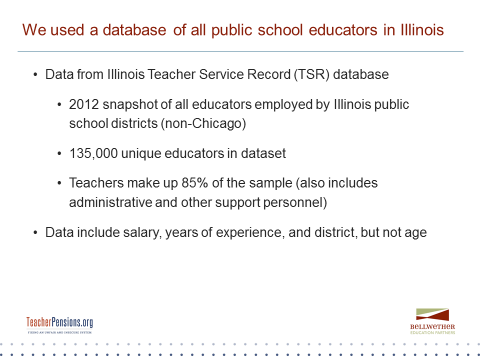

To test our hypothesis, we examined a dataset comprised of every educator in the state of Illinois. The dataset allows us to look at characteristics of Illinois’ educator workforce in 2012, including variables such as an educator’s salary, in-state experience level, and district experience.

Our findings are still preliminary at this point, but they suggest that teachers are unevenly distributed across the state, and that pensions magnify inequities according to salary and experience level. Not only do poor communities have lower-paid, less-experienced teachers, they're also receiving less from state pension plans. When we cut the state’s districts into five poverty quintiles, we found that educators in the state’s richest districts often had higher salaries, experience levels, and subsequently, pension benefits. Additionally, other variables, such as who contributes to the plan and how much can, increase inequity. In Illinois, districts only pay a small portion of their workers’ contribution and the state picks up the remainder. Here, too, richer districts are getting a subsidy from all state taxpayers.

Stay tuned in the upcoming month as we finalize our research. To learn more about pensions the teaching workforce, check out our past publications.