The following is a guest post from Martin F. Lueken, Ph.D., the director of fiscal policy and analysis for EdChoice, formerly the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice.

Like most states, Nevada faces challenges with rising pension costs. According to University of Arkansas economist Robert Costrell, per-pupil school pension costs have doubled nationally in the last 10 years. This trend is similar in Nevada. The contribution rate for school districts has increased by about 40 percent since 2002. Annual payments (adjusted for inflation) devoted to paying off the state’s pension debt, however, more than doubled from $540 to $1,200 per student. Unfortunately, there’s no sign of when this trend will break in the future absent structural reform.

Last year, Nevada passed the nation’s first universal education savings account (ESA) program (the state’s Supreme Court is currently reviewing the constitutionality of the law). In addition to the non-fiscal benefits attached to educational choice, the program can relieve pressure for district budgets from rising pension costs (for each one million dollars spent on the program, I estimated that the state would save almost half of that amount, while school districts would save almost $700,000). These savings would give district officials flexibility and more control over their budgets. One option they have would be to reallocate these savings to shore up retirement-related obligations.

Nevada’s effort to provide true and meaningful educational choices to its citizens by enacting the ESA program is needed. But to maximize the program’s effectiveness, it’s important for Nevada to have the right policies in place to allow its education system to fire on all cylinders. This includes a fluid educational labor market where teachers can move from one sector to another in response to changes in supply and demand. One area with potential to create inefficiencies in its teacher labor market is pensions.

In this post, I examine in detail how Nevada’s pension plan for teachers operates and show how it incentivizes teachers to make employment decisions around arbitrary points in their careers.

How Nevada’s Pension Plan Works

Public school teachers in Nevada automatically become members of the Public Employees’ Retirement System (PERS) of Nevada. The pension plan is a traditional (or “final salary”) defined benefit (DB) plan. Teachers can vest in the plan after five years, meaning that they become eligible to receive a pension. If a teacher leaves the system before vesting, she may only take a refund of her own contributions. Vested teachers can collect a normal pension starting at age 65. Teachers who leave with 10 years of service can start collecting a pension at age 62, and teachers with 30 years of service can begin collecting a pension immediately. Vested teachers can also receive a reduced benefit if they retire before age 65. Depending on a teacher’s years of service, his benefits are reduced by 4 percent to 6 percent each year younger than his normal retirement age.

The value of a teacher’s benefit is determined by how many years she works, the average of her highest three consecutive years of salary (final average salary, or FAS) and an accrual factor of 2.5 percent.

Let’s start with an example. A teacher who started at age 25, worked in the system for 29 years, and has an FAS of $50,000 can expect to receive an annuity worth:

(2.5 percent) x (29 years) x ($50,000) = $36,250 per year

While she would leave at age 54, she cannot start collecting her benefit until age 62. If she lives until age 80, then she would collect 18 years’ worth of pension payments, and the total value of her pension would be $652,500 (ignoring factors like inflation and cost-of-living adjustments).

Now consider the same teacher, but this time she works an additional year to reach her 30th year of service. Her annual benefit would be worth $37,500. While similar to the annual benefit she’d receive if she left after 29 years, she would be eligible to immediately collect a pension starting at age 55. This is a huge difference. The value of her pension would be $937,500. This large jump (44 percent) in the value of her pension benefit occurs because she would collect 25 years worth of pension payments, up from 18. By working just one additional year and reaching her 30th year of service, she can receive 7 additional years worth of pension payments.

What a difference a year makes!

The teacher in the first example has a very strong incentive to stay until her 30th year. With such a strong incentive built in to the system, however, some teachers will likely stay regardless of their life circumstances or preferences. Those who cannot remain for an additional year will consequently face a severe financial penalty for their mobility – not staying for her 30th year means the teacher in our example gives up $285,000 worth of pension payments.

The story doesn’t stop there, though. Let’s consider an additional year of work. By working her 31st year, her annual benefit would be worth $38,750 – an increase in the annual benefit of $1,250. But the total value of her retirement would actually decrease from $937,500 to $930,000, because by working an additional year, she is giving up one year’s worth of pension payments. That is, she will now collect pension payments for 24 years instead of for 25 years. In other words, the year of pension payments she foregoes is greater than the additional pension benefit she accrues from working an extra year. Financially, she would be better off retiring instead of continuing to teach in the system.

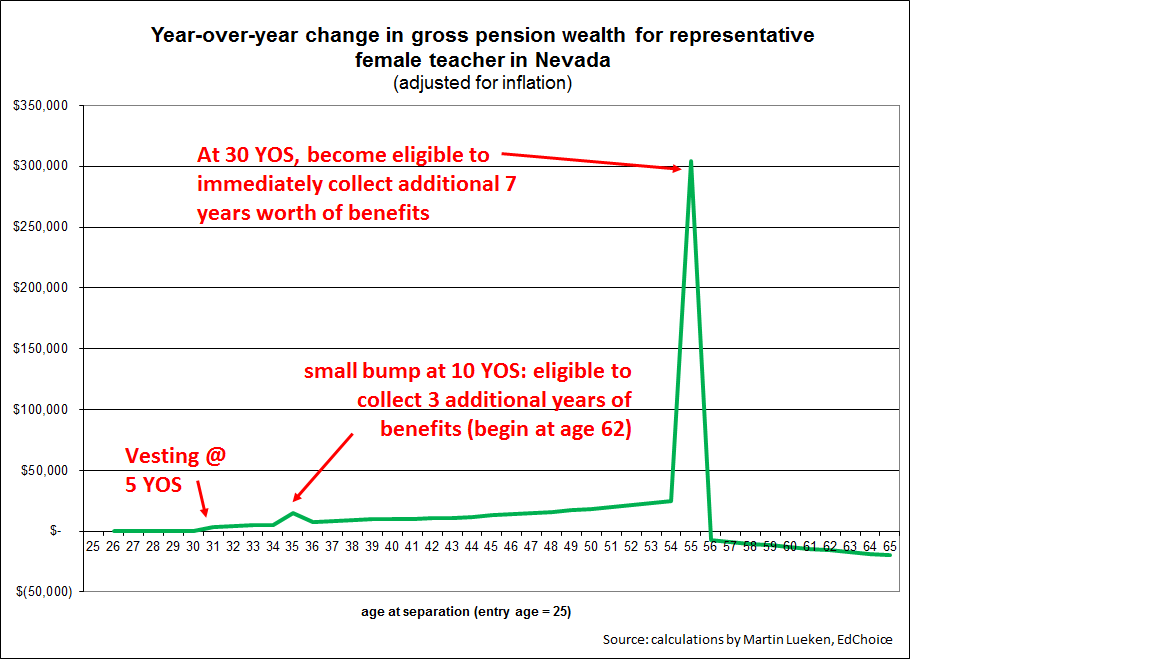

The adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” rings particularly true for examining pension incentives. The graph below clearly shows the financial incentives Nevada’s pension system places on teachers.* It plots the year-over-year change in pension wealth for a teacher who begins teaching in Nevada at age 25. This example uses the pay schedule for the Carson City School district.

Imagine that a teacher receives a one-time lump-sum payment worth his pension wealth when she retires in a given year. This amount (i.e. the value of his pension wealth) varies with the timing of her decision to leave covered service. For each year in his career which she might leave, the value on the graph at a given point is how much the value of her retirement benefit changes from working an additional year. It is not the value of her pension wealth itself.

Before vesting, she is not eligible to receive a pension. Her gross pension wealth is zero (and therefore the change from year-to-year during this period is zero). If she leaves in year five (when he is 31), she can collect a pension starting at age 65 because she will then be vested in the system. Her pension wealth at this point would be worth $3,671.

The value of her retirement grows slowly and steadily up to age 54, at which point she’s given 29 years of service to the state. Working his 29th year generates an additional $24,586 in pension wealth. She can collect a pension starting at age 62 if she leaves Nevada’s system at this point. Her total pension wealth is worth almost $400,000 (not shown in the graph).

If she works year 30, then she will increase her pension wealth by $304,288 for this single year of service. This will boost her total pension wealth up to more than $700,000. In terms of her retirement, this would be an extraordinary year in his career.

If she works another year, then her pension wealth will actually decrease by $7,411. Financially, she’ll be better off retiring after his 30th year instead of continuing to teach. Of course, numerous factors drive these decisions (health, family circumstances, etc.). But it’s not hard to imagine how this financial incentive can become a serious consideration that is difficult for a teacher to ignore—if it wasn’t a main consideration for an individual before. Workers in general are very responsive to these incentives.

The key question is: What is so special about the points where these spikes occur?

There is no logical answer to this question; it is an artifact of an outdated retirement system designed long ago for a different kind of work force. And there is evidence that it might not serve the purpose that the plan was intentionally designed to serve. According to a report by Bellwether Education Partners, just over half of teachers in Nevada (55.3 percent) vest, and only 28.7 percent of Nevada teachers stay until normal retirement age. Like most other plans that cover teachers, Nevada’s plan rewards just a small minority of teachers who stay long enough to reach retirement eligibility.

Incentives for teachers in Nevada’s pension plan

The behavior of Nevada’s pension plan is typical of most other FAS DB plans, in that it backloads pension benefits. The example above demonstrates how two forces at play in these plans work to create inefficiencies in the teacher labor market. Parameters in the plan work to “pull” teachers already in the system to remain until arbitrary points in their careers, and “push” teachers out after these points—regardless of their life circumstances, passion or dispassion for teaching and other job conditions.

First, strong incentives work as a “pull” to incentivize teachers to continue teaching while covered by the system up to the spike. That is, these factors incentivize teachers who might otherwise separate from covered service to “hang on,” regardless of whether they want to (perhaps they are no longer suitable for the job or burned out). Second, teachers face strong incentives to retire early. The period after the spike serves as a “push” to incentivize teachers to leave teaching after 30 years, regardless of whether they have good years left to give or whether they desire to continue teaching. Such plan designs are arbitrary and drive a wedge into the teacher labor market.

This is not ideal for Nevada’s teacher labor market, which supplies public schools (including charter schools, which are required to participate in NVPERS) and private schools. Consider that Nevada’s system, like many similarly structured DB plans offered to most public school teachers throughout the country, is structured to:

- create a disincentive for teachers to switch between public and private schools;

- create a disincentive for potentially effective short-term teachers from entering teaching;

- create an incentive for effective teachers to retire early even though they may still have good years to offer;

- create an incentive for less-effective teachers to enter the profession in place of those who were enticed not to enter;

- retain some teachers longer than optimal, regardless of effectiveness; and

- encourage teachers to enter and stay in administration to spike their final salary, regardless of whether they are suitable for such positions.

Implications for Nevada’s K-12 schools and policy recommendations

Last year, Nevada passed the largest ESA program in the country with the goal of expanding educational options for all Nevada families. To achieve this goal, the state will need to attract high-quality schooling options and the staff to run them. It will need to ensure that policies are conducive to attracting and retaining a high-quality and responsive teaching workforce. As it stands, the underlying incentives in its pension plan runs counter to this goal.

Put simply, the system is not designed to serve all teachers. It penalizes teachers who leave before reaching retirement eligibility, regardless of an individual’s life circumstances.

Nevada could alleviate this potential problem by offering teachers more choices in the kinds of retirement plans offered. Given the idiosyncratic incentives embedded in its current retirement plan—and because it imposes mobility costs on mobile teachers—the state should at least offer a defined contribution (DC) plan as a choice for its employees. Not only might mobile teachers have stronger preferences for them, but some teachers may also not know with certainty whether they will work in the system for an entire career. The portability that comes with a DC plan would be a welcome option for some teachers.

In addition, because benefits are tied directly to contributions, the system is much less likely to accrue large unfunded liabilities.

Nevada’s pension debt is the equivalent of $27,750 per student.

Alternatively, the state could increase the portability of its current plan by allowing refund claimants access to employer contributions. Under the current plan, teachers who leave prior to retirement eligibility and opt for a refund receive only their contributions (currently 12.25 percent of creditable earnings) plus interest. Employees under NVPERS do not enroll in Social Security, however, as many other states do. Given that some financial experts usually recommend savings rates of about 15 percent to 20 percent for retirement security, teachers who take a refund may be under-saving. Allowing access to even a portion of the employer’s contributions (about 13 percent in FY 2014) could help teachers meet this target. Although this option addresses portability, it would not improve funding and sustainability problems.

Rising costs and arbitrary incentives are just two reasons for Nevada to pursue pension reform. In light of its bold step to enact a universal ESA program fit for the future, its pension plan remains in the past.

*The graph is based on a measure which economists Robert Costrell and Michael Podgursky coined “pension wealth.” It can be computed for any year that a teacher leaves service (and the system). Pension wealth is the present discounted value of the stream of pension payments she can receive, discounted for survival probabilities. It is a lump sum. Present discounted value converts dollars given for future points in time into today’s dollars. I also adjust all figures for inflation. I assume nominal interest is 5 percent and inflation is 2.5 percent.