Last week the state of New York announced that, due to gains in the stock market, the employer contribution rate for its teacher pension plan, NYSTRS, would fall from 10.62 to 8.86 percent of payroll. This is obviously good news, and it will save New York school districts an estimated $300 million in the 2019-20 school year.

NYSTRS is often cited as one of the leaders in the public pension world, mainly due to its relatively high funded ratio (97.7 percent as of 2017). Unlike other states, where contribution rates are set in statute or determined annually by the whims of state legislators, NYSTRS regularly contributes exactly what its actuaries say the plan needs.

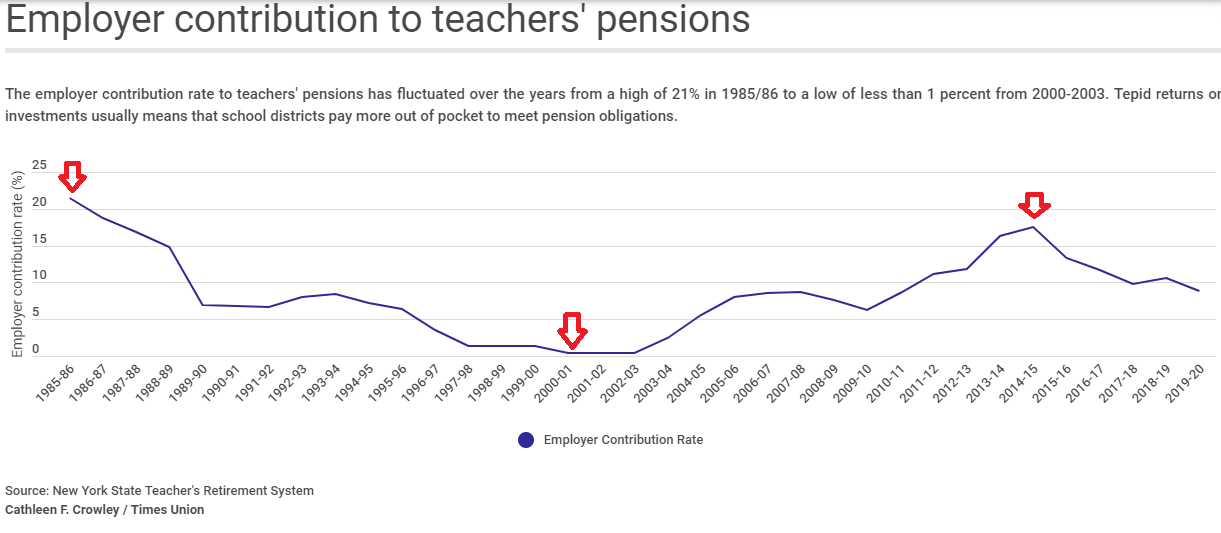

And yet, there are problems with this model too. As this excellent graphic from Cathleen F. Crowley at the Albany Times Union shows (I added the arrows), the downside of this approach is extreme volatility. NYSTRS' employer contribution rates have fluctuated from a high of 21 percent in 1985-86, down to less than 1 percent from 2000-3, only to rebound up to 17.5 percent in 2014-15. School districts are handed these contribution rates with no choice, and they can force significant changes to district budgets when contribution rates can nearly triple in five years' time, as they did from 2009-10 to 2014-15, or halve, as they've done since then. Districts are given a few months of advance notice--the rates for 2019-2020 were just announced, for example--but this volatility can still make for painful setbacks in some years or surprise windfalls in others.

New York's roller coaster contribution rates and high funding ratios may earn plaudits on the financial side, but they have not made the state immune to the benefit cuts affecting teachers in other states. In fact, NYSTRS has aggressively cut benefits for new workers over time, and today it operates six tiers of benefits that depend on the employee's start date. New workers hired after 2012 have the least generous benefits, followed by those hired between 2010 and 2012, and so on. New York also requires teachers to stay 10 years before qualifying for retirement benefits, a requirement that would be illegal in the private sector.

All of this should serve as a reminder that a plan's financial status may or may not have any relationship to how well it works for its members. NYSTRS has maintained its high funding ratio at the expense of both employees and employers.