School districts are paying more money for teachers. Meanwhile, teachers are receiving less money as income.

How is this possible?

The difference comes down to retirement costs and the large unfunded “pension debts” that states have accumulated, creating a massive disconnect between teachers’ total compensation and their actual paychecks. As policymakers attempt to raise teacher salaries, their efforts will fail unless they act to rectify the compensation-versus-salaries disconnect.

This problem matters for school leaders and state policymakers because it means they’re buying less teacher labor for every dollar they invest — and that efforts to raise teacher salaries will fail or be far less successful than state and federal leaders are proposing.

It matters to teachers, who feel it in the form of reduced paychecks. Teachers struggle to buy food, pay their mortgage, or send their child to day care using compensation from pension debt payments.

And it matters to students because so many of the dollars being invested in their education aren’t making it into classrooms. While per-pupil expenditures have risen substantially over time, much of that new investment ends up paying for the pension debts accumulated in the past.

This piece will walk readers through three graphs. The first two use data from a Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) survey called the Employer Costs for Employee Compensation. The survey findings allow us to see how teacher compensation is changing, overall and by component. School districts are facing higher costs to employ teachers, even as teachers are receiving lower salaries.

The main cause of this disconnect is not new taxes or teachers getting more paid time off. It’s also not rising health insurance premiums. Instead, it’s all on the retirement side: Teacher salary costs have risen 44% since 2004, while retirement costs have risen by 322%.

Unfortunately, data from the Equable Institute show that these growing retirement costs are not benefiting workers. In fact, states have been cutting benefits for workers even as they face rising costs, thanks to negligence in how they fund their teacher pension plans. States collectively now face more than $800 billion in unfunded pension liabilities. These pension debt costs are crowding out other potential investments in education.

This analysis is the first in a series of policy considerations for how states can get their pension debts under control and start directing more money into teachers’ pockets.

The Growing Disconnect Between Salaries and Total Compensation

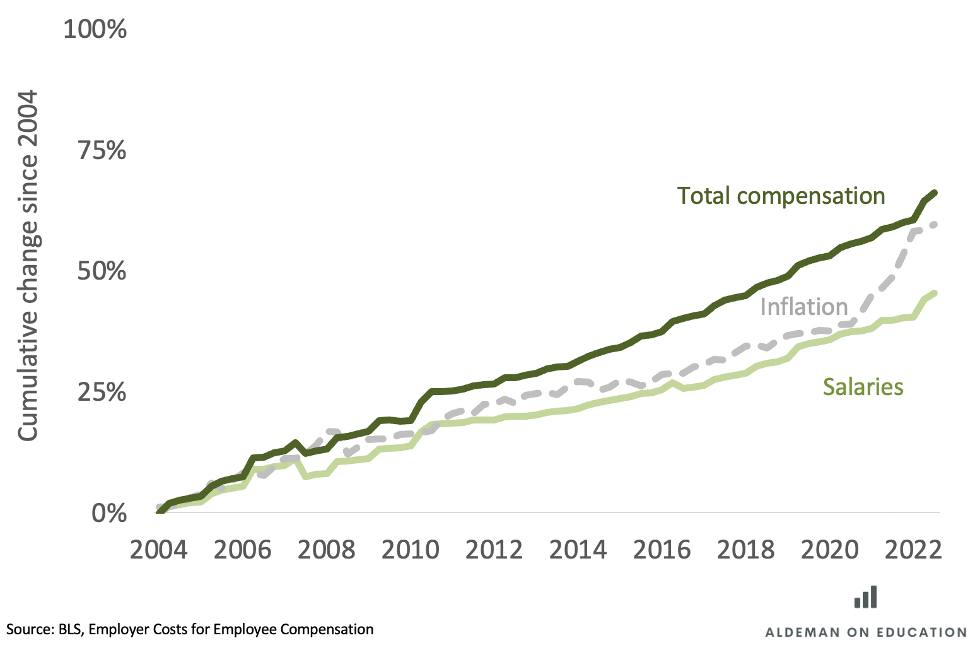

The BLS survey on Employer Costs for Employee Compensation has been tracking compensation data since the 1980s. For most of those years, it lumped together all “teachers,” including those at private schools and postsecondary teachers. But starting in 2004, it began to break out data separately for “primary, secondary, and special education school teachers” who work in the public sector. The data allow us to see how K-12 public school teacher compensation has changed over time (Figure 1).

Teacher salaries (light green) have risen in nominal dollars, but they have not kept up with inflation (gray dotted line). Especially as inflation has risen rapidly in recent years, teacher salaries have not kept up.

The same trend is broadly applicable across the American workforce. Salaries tend to be “stickier” than inflation, and it takes time for salaries to catch up — particularly when inflation rates quickly change. That is especially true for workers in the public sector, where salaries are set in contracts that might only be negotiated every two or three years.

Figure 1 also shows how total teacher compensation is changing over time. This reflects the full amount that school districts are paying to employ a given teacher — not just salary but also paid time off, supplemental pay, taxes, and benefits like health insurance and retirement. As the chart shows, the total compensation package of public school teachers has outpaced inflation. School districts are paying more, while teachers are getting less.

Figure 1: Teacher Salaries Are Not Keeping Up With Inflation, but Total Compensation Is

Another way to look at this trend is to consider salaries as a portion of a teacher’s total compensation. Over this time frame, salaries shrunk from 74% to 65% of the average teacher’s total compensation.

The Cause of the Disconnect: Retirement Costs

So what’s driving the total compensation-versus-salaries disconnect? It’s mainly retirement costs. The BLS survey breaks down total compensation into six categories:

- Ordinary salaries and wages.

- Benefits, including paid leave.

- “Supplemental” pay for work outside the regular day.

- Taxes and other legally required benefits (including Social Security and Medicare).

- Insurance benefits.

- Retirement benefits.

For public school teachers, supplemental pay makes up the smallest percentage of their total compensation, at just 0.4%. Taxes and paid leave each consume about 4.5% of compensation, and those percentages have not changed much over time.

Health insurance is largely a success story. Like other employers, school districts had rapidly rising health insurance costs leading up to the 2010 passage of the Affordable Care Act. But since then, costs are rising much more steadily. School district health insurance costs rose by 6.7% per year from 2004 to 2010. From 2011 to 2022, they rose by only 2.2% per year, less even than the rate of inflation.

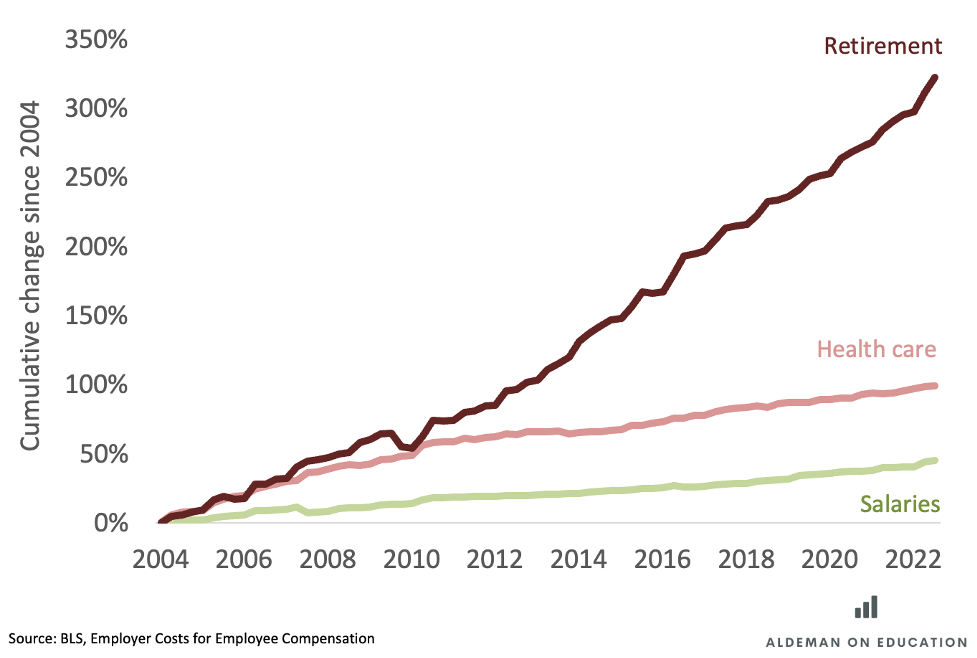

Teacher retirement costs are the big outlier. They rose 7.9% per year from 2004 to 2011, and they’ve continued to rise by 8% per year since then. Figure 2 shows the cumulative change in retirement costs since 2004. As in Figure 1, teacher salaries are represented by the light green line. Health care is in pink: It grew rapidly for a while but has since followed about the same growth rate as salaries. Retirement costs, in dark red, began diverging sharply from the other two around 2010. Overall, teacher salaries have grown by 44% since 2004, health insurance costs have risen 99%, and retirement costs are up by a whopping 322%.

Figure 2: Teacher Retirement Costs Are Rising Much Faster Than Health Care or Salaries

This might be less of a problem if the increase in retirement costs led to a similar increase in individual teachers’ expected retirement payouts. But that’s not what’s happening. Quite the opposite: Thanks to poorly funded pension plans, states have increased contribution rates while simultaneously cutting retirement benefits for workers.

The Growth in Pension Debt Costs

A pension is a promise to workers. In this case, state legislatures have promised teachers who qualify for benefits guaranteed monthly payments from the time they retire until they die. To make sure they have enough money to pay for those promises, states have to make assumptions to determine the future value of those pensions. They also need to estimate how much money to save today and how fast those investments will grow over time.

Pension plans break down their costs into two buckets. The first is what pension actuaries call the “normal cost,” or the estimated cost of the retirement benefits workers earn in a given year. If any of these estimates is wrong, the plans can accumulate unfunded liabilities — a form of debt that’s owed to the pension plan.

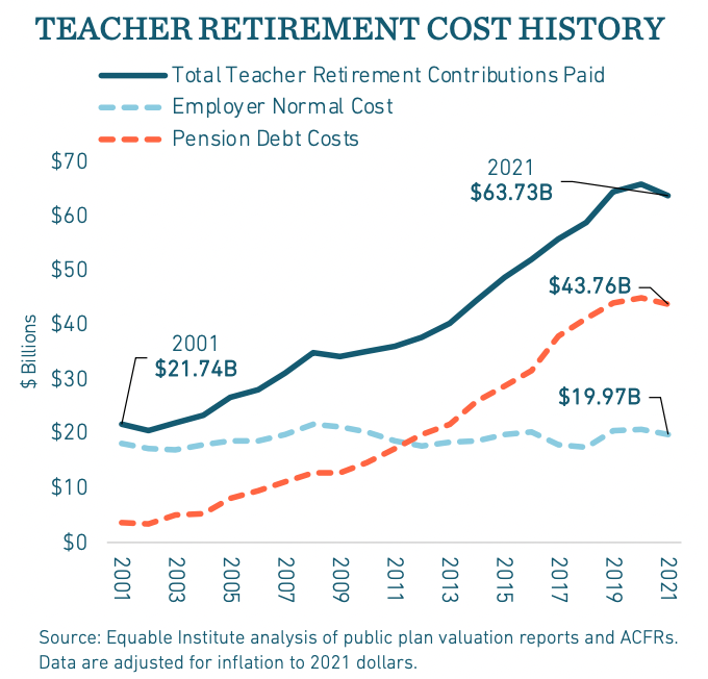

Figure 3 comes from a new report from the Equable Institute. It shows how teacher pension costs have changed over time. The light blue dotted line shows that the employer share of the normal costs — the value of the retirement benefits teachers receive — has gone down a bit over time, reflecting a slow phase-in of benefit cuts for new workers.

Meanwhile, the red dotted line in the graph shows pension debt costs — the amount of money states and school districts are paying to address the shortfalls accumulated in previous years. As the chart shows, all of the growth in pension costs over the past two decades has come from these debt payments.

Figure 3: States and School Districts Are Spending More on Retirement Benefits While Workers Receive Less

The Equable Institute report estimates that states and school districts are spending $44 billion a year on these pension debt costs. They leave it for us to imagine what schools might be able to do with that extra $44 billion. By my back-of-the-envelope math, that money could raise the average teacher salary by almost $14,000 per year. While the situation varies across states and school districts, at the national level, the solution to raising teacher salaries must start with addressing the growing teacher pension debt costs.

How to Solve the Pension Problem and Raise Teacher Salaries

As the Equable Institute report shows, states like Wyoming, South Dakota, Delaware, Nebraska, and Florida have all done a comparatively good job of managing the growth in pension costs. What lessons can other states borrow from them?

The biggest one, by far, is to set more reasonable investment return targets. States have an incentive to be overly aggressive with their pension assumptions so that on paper they don’t need to contribute as much along the way. But that only hides the real costs and forces plan managers to seek out riskier investments. Lowering the assumed rate of return would cause some short-term pain as budget makers faced up to the true costs, but over time it would help plans get back on sound financial footing.

State leaders should also stop passing the buck on to school districts. Right now, state leaders can say they’re increasing education budgets while they turn around and raise the pension contribution rates that all school districts are required to pay. This two-step allows states to shirk their pension responsibilities, and it’s not fair to school districts. After all, states have an easier time raising revenue than local districts, and they can do so in more progressive ways than local districts can. And since state leaders were responsible for creating the unfunded liabilities in the first place, they should be responsible for paying them off.

Treating pension debts as a long-term state obligation, just like any other state debt, would allow states to own up to the problem and come up with a responsible plan to address it over time. In turn, that would leave school district leaders to focus on raising teacher salaries and getting more money into their paychecks. But this all hinges on policymakers understanding and acknowledging their large and growing pension debt problem — and doing something about it.

In the next installment of this series, I’ll translate these pension costs into per-pupil and per-teacher numbers for the largest school districts in the country.