Teacher pensions protect teachers from certain risks. Teachers don't have to make their own investment decisions, meaning they don't have to worry about how much to save, how to invest, or whether they'll outlive their savings. The pension plan bears all those risks on behalf of teachers.

But pension plans carry another risk--attrition risk. Because pension plans are back-loaded, attrition risk is the possibility that a teacher won't stick around long enough to qualify for the larger benefits waiting for those who stay. Teachers rarely stay a full career in teaching, let alone in the same state and the same pension plan. Even if an incoming teacher may have every intention of staying a full career, her pension wealth will be tied to how long she is willing and able to stay. If life gets in the way--if a spouse wants to move, a parent gets sick, or she simply tires of teaching--her retirement wealth will suffer.

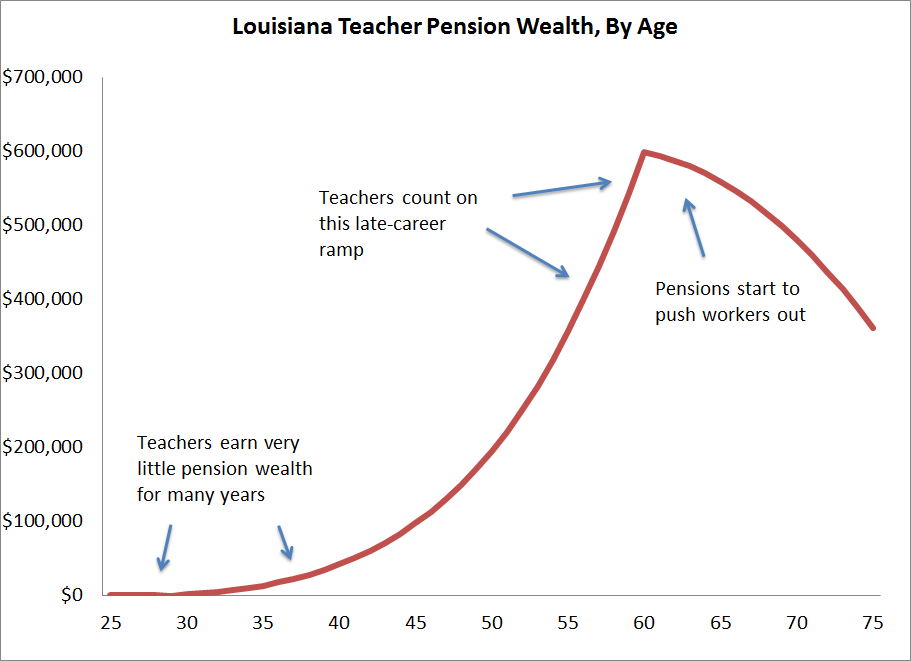

One way to show attrition risk is simply to look at how retirement benefits grow in pension plans. The graph below shows how retirement benefits accrue for a Louisiana teacher. She earns relatively modest benefits early in her career, less than what she could earn in the private sector under a cost-neutral 401(k)-style plan. Most teachers fall into this bucket--Louisiana's actuaries estimate that half of the state's teachers will leave before reaching just seven years of service. They won't get close to the much more generous benefits offered to teachers who stay for their full career. If a teacher does stay that long, her retirement wealth will more than triple between the ages of 50 and 60. But that's only if she stays that long.

This is a pretty classic case of attrition risk that exists in pension plans all across the country. But Louisiana also provides a recent example of extraordinary attrition risk.

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, the Orleans Parish School Board dismissed 7,500 employees without regard to age, years of service, or expected pension benefits. Not all of these teachers would have qualified for the significant back-end benefits promised by the pension system, but some would have. Imagine being a 50-year-old teacher in Louisiana with 25 years of experience when Katrina hit. You would have been accepting 25 years of lower pay in exchange for the promise of a solid pension in the near future. You're counting on those next ten years, when the value of your pension would triple. But when the hurricane hit, you not only lost your job, you also lost out on the opportunity to grow your pension.

Legally, the fired workers are pressing their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. They're arguing that they were wrongfully terminated after the storm and are asking for back wages. But, crucially, they are not asking for any compensation in the form of lost retirement wealth. That's because teachers don't have a right to future pension wealth accruals. Even in states with strong legal protections that restrict the state from reducing its pension formula, individual teachers can still be fired and taken off the pension wealth curve. That's another form of attrition risk.

The New Orleans story is an extreme example, but attrition risk is real and important for teachers to understand. Unless teachers know, with absolute, 100% certainty, that they're going to stay in the same pension system for their entire career, they would likely be better off in less backloaded retirement plans that offer more retirement savings earlier in their career.

Update: I added two more points worth mentioning here. One, very few New Orleans teachers stay for long enough to qualify for a significant retirement benefit. Two, Louisiana teachers are not enrolled in Social Security, meaning they're particularly vulnerable to a poor retirement system. We think all teachers should be given the retirement income protection that Social Security offers.