Unnecessarily high turnover is a problem in any field. Turnover results in increased costs in lost work during vacancies, recruitment, and retraining, all of which contribute to overall productivity losses and lower quality of service. In the public sector those services are the ones that we all benefit from: police and fire protection, government offices ranging from the Department of Transportation to the Environmental Protection Agency, and in education, public school teachers. How much does turnover affect various public sector occupations? We can use state pension calculations to find out.

In the state of California, teachers and other public sector employees are channeled into two different retirement systems. Teachers participate in the California Teachers State Retirement System (CalSTRS). All other state and public agency employees participate in the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS). CalSTRS represents the largest educator-only pension fund in the world and boasts a total of 862,192 members and approximately $191.1 billion in assets. CalPERS totals 1,678,996 members: 30.3 percent are state employees, 30.7 percent are local public agency employees, and 39 percent are non-teaching school employees (this is made up of non-credentialed employees such as janitorial staff, secretaries, attendance monitors, etc.).

To compare turnover rates among public sector workers, we compiled data based on the actuarial assumptions found in CalSTRS and CalPERS’ Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports. While the data represent the plan’s assumptions for the future, not the actual rate, the assumptions are based on semi-regular experience studies that look at recent historical trends (for example, CalPERS updated their assumptions in 2010 based on historical data from 1997-2007).

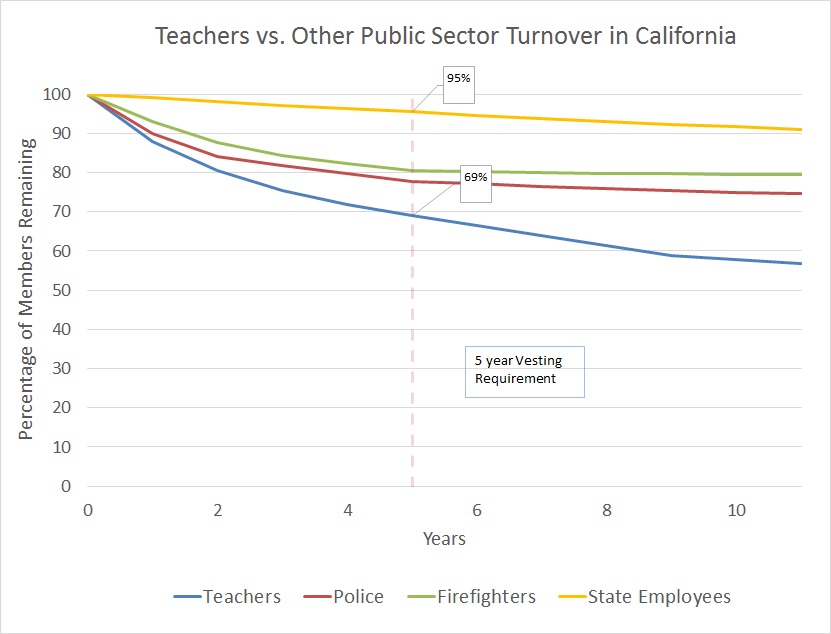

We compiled this turnover data for teachers, police officers, firefighters, and individuals employed by the state of California, California State University, or California community colleges who were not involved in law enforcement (labeled as “state employees”). The graph below shows the results.

Sources: CA Public Employee’s Retirement System and CA Teachers’ Retirement System

For all groups, turnover occurs most during the first few years of service and flattens in the later years. However the drop-off is steepest for teachers (blue) but very low for state employees (yellow), over 90 percent of whom remain even after ten years.

Now compare teachers and state employees with the police and firefighters. Where state employees have a less than 5 percent cumulative attrition within the first five years, police and firefighters have more than triple this, with 20 percent or more attrition. Teachers in California have nearly six times the attrition of state workers, with over 30 percent turnover during the first five years.

Teachers are often lumped in with other public sector workers, but the turnover rates of the teaching profession places them in a much more volatile position than other state or local government positions. On the national level, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, teachers had nearly twice the annual turnover rate as state and federal government workers.

In terms of retirement, these turnover rates also give us a picture of the retiree pool. To even qualify for a minimum pension in California, teachers, police, firefighters, and state employees must serve at least five years. Where 95 percent of all state employees meet the five year vesting requirement, the numbers are steeper for teachers. With a turnover rate of over 30 percent at the five year vesting mark, roughly one-third of California teachers will leave the profession before qualifying for even a minimum pension. Furthermore teachers from California are excluded from Social Security, leaving a substantial group of teachers with neither a state pension nor Social Security.

In certain states, teachers are placed in the same retirement system as all other public sector workers. But as the turnover rates suggest, such systems may be treating unequal employee groups equally. While California teachers are channeled into a separate retirement system from other public sector employees, both CalSTRS and CalPERS follow the same structure of a traditional defined benefit pension where benefits are not tied to contributions and are back-loaded toward the end of the employee’s career. Traditional defined benefit pension plans may make more sense for the more stable pool of public sector state office employees, but for teachers, the current system simply doesn’t have the same breadth of coverage when significant portions of teachers will not receive a pension at all. Teachers are a unique labor force whose trends differ from other traditional state and local government workers. States should in turn consider the varying patterns of their labor force so that they can build a retirement system that better fits the demands of its employees.

Taxonomy: